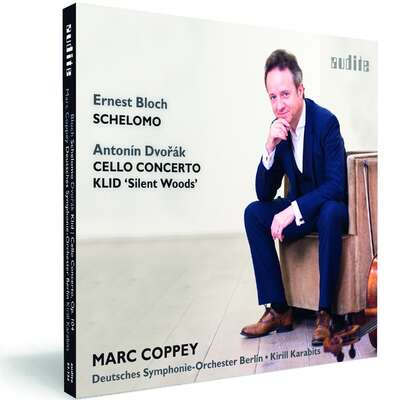

Departing from home: in Schelomo, Bloch examines his cultural and religious roots; in his cello concerto, Dvořák illustrates both his old and his new native countries, whilst the forest scene Klid represents a bridge and also an atmospheric reminiscence.more

"This sort of playing has me reaching for the rewind facility just for the pleasure of enjoying it a second or third time." (Gramophone)

Details

| Dvořák: Cello Concerto & Klid - Bloch: Schelomo | |

| article number: | 97.734 |

|---|---|

| EAN barcode: | 4022143977342 |

| price group: | BCA |

| release date: | 30. June 2017 |

| total time: | 68 min. |

Bonus Material

Informationen

Having spent nearly two decades playing solo recitals and chamber music, as well as performing alongside renowned orchestras, Marc Coppey turns to three classics of the cello repertoire. Following the album of cello concertos by Haydn and CPE Bach, audite now presents the second disc with the French cellist.

Departing from home: in Schelomo, Bloch examines his cultural and religious roots; in his cello concerto, Dvořák illustrates both his old and his new native countries, whilst the forest scene Klid represents a bridge and also an atmospheric reminiscence.

In all three works, the composers look from Europe to America and vice versa: Bloch's Schelomo was written immediately before his crossing to America; Dvořák composed his B minor Cello Concerto only once he had arrived there. Klid (Silent Woods) sits in between: before departing for America, Dvořák arranged this work, originally for piano duet, for cello and piano, to be played during his farewell tour. In this format, the piece became so popular that he went on to produce an additional version for cello and orchestra.

Antonín Dvořák and Ernest Bloch provide clear performing instructions, but also demand a high degree of free interpretation. Marc Coppey manages to realise both of these aspects, maintaining a convincing balance and communicating intensively with the orchestra. He does not need to demonstrate his virtuosity through overly hasty tempi: instead, he follows the recommendations found in the scores. This greatly benefits the clarity, vividness and eloquence of his interpretations. The Deutsches Symphonie-Orchester Berlin and Kirill Karabits prove congenial partners.

Reviews

Classica – le meilleur de la musique classique & de la hi-fi | Numéro 201 - Avril 2018 | Yannick Millon | April 1, 2018

La rhapsodie hébraïque Schelomo d'Ernest Bloch, basée sur la vie du roiMehr lesen

Radio-Télévision belge de la Communauté francaise | 08 janvier 2018 | January 8, 2018 | source: https://www.rtbf... BROADCAST

Après près de 20 ans de récitals et de musiques de chambre pourMehr lesen

Fanfare | December 2017 | Raymond Tuttle | December 1, 2017 | source: http://www.fanfa...

I must admit that I sighed a little as I got ready to review this CD. “Here we go, another Dvořák Cello Concerto,” I thought. Even so, myMehr lesen

Steven Kruger, Huntley Dent, and Jerry Dubins all beat me to reviews of this program because they were working with a download. (I’m old school, preferring, when I can, to review a physical CD.) I made a point of not reading their reviews until I had formed my own opinion and written the previous paragraph. Dent was similarly impressed with the evenness and beauty of Coppey’s tone. Kruger also liked the program very much. Dubins, on the other hand, wrote, “In much of the technically difficult passagework, cellist Marc Coppey sounds labored, and even in relaxed moments of lyrical calm his tone, which is a bit on the grainy side to begin with, is not the loveliest I’ve heard. But Coppey’s technical and tonal shortcomings are minor beside Kirill Karabits’s lackadaisical conducting and the German Symphony Orchestra Berlin’s lapses in good behavior.” Much as I respect Dubins’s opinion, I don’t share it. (Maybe he should check his computer cables!) In a very competitive field, in which cellists such as Rostropovich, Starker, and Piatigorsky all have given us excellent recordings of this music, Coppey does not supplant them—but he has no reason to be ashamed in their august company. If you’re looking for a modern recording of these works in very fine sound, I have no hesitation about recommending this new release to you.

The Strad | November 2017 | Joanne Talbot | November 1, 2017 | source: https://www.thes...

Partnered by expressively sensitive orchestral playing from the Deutsches Symphonie-Orchester Berlin under Kirill Karabits, coupled with a beautifully clear resonant recording, there is simply everything to recommend in this performance. [...] This is undoubtedly one of the finest versions of this much-recorded work to date.Mehr lesen

American Record Guide | November / December 2017 | David W Moore | November 1, 2017 | source: http://argsubson...

The selling point here is the order of the program and the liner notes by Coppey with a further set by Habakuk Traber. These present Schelomo as aMehr lesen

These works are favorites of mine, and I am happy to hear them in this context. The recorded quality is excellent, clean and dramatic; but the interpretations are not always as impressive as the sound. Coppey plays beautifully, but the orchestra is not always clear in its phrasing—I miss some of the answers to the cello’s side of the conversation. The dramatic statements are fine on both sides, but the relations are often more vague than they should be, and the orchestra is not always audible in softer passages.

ClicMag | N° 53 Octobre 2017 | Jean-Charles Hoffelé | October 1, 2017

L'unique concerto que Dvorak écrivit pour Hanus Wihan (qui renonça à saMehr lesen

Fanfare | October 2017 | Jerry Dubins | October 1, 2017 | source: http://www.fanfa...

New recordings of Dvořák’s B-Minor Cello Concerto continue apace, but it has been quite a while since a new recording of Bloch’s “HebraicMehr lesen

I may have been a bit unkind to Bloch’s Schelomo in a performance by Truls Mørk in 28:6, when I referred to the “Ben-Hur, Hollywood kitsch” aspects of the score. It’s true—and the composer admitted as much—that the “Jewish character of the work was not achieved using ancient melodies.” Bloch was, however, deeply moved and inspired by the book of Ecclesiastes, authorship of which is attributed to the aged King Solomon, who, as an old and despairing man, had seen the follies of life and concluded, in pessimism and sorrow, that “All is vanity.”

According to Bloch, the idea for Schelomo actually had its beginnings in 1915 in sketches for a large choral-orchestral setting of the Ecclesiastes text. But he wasn’t fluent in Hebrew and the translations into German, French, and English just didn’t seem to work. It wasn’t until Bloch met the cellist Alexander Barjansky that his path forward became clear. Solomon would speak not in words but in a language more immediate, direct, and understandable by audiences of diverse languages and dialects. Schelomo would be a portrait of the ancient king—represented by the solo cello—recalling and commenting on the swirl of events and experiences—represented by the orchestra—that shaped his life and led him to his profound loss of faith in humanity.

As booklet note author Habakuk Traber points out, “Schelomo is the only piece in Bloch’s oeuvre to have a dark ending.” But Traber didn’t need to tell us that; Bloch tells us that himself: “Even the darkest of my works end with hope. This work alone concludes in a complete negation, but the subject demands it!” And no wonder. The work was completed in 1916 while the composer and his family were still in Geneva during some of the darkest days of World War I. By the following year, Bloch had emigrated to the U.S., and Schelomo received its first performance on May 3, 1917 in Carnegie Hall. The soloist was Hans Kindler, principal cellist of the Philadelphia Orchestra under Stokowski, and the concert was conducted by Artur Bodanzky.

Dvořák’s B-Minor Cello Concerto is so familiar on record and on concert stages across the globe that it needs no introduction. The album note does observe, however, that in at least one way Dvořák’s concerto is a mirror image of Bloch’s Schelomo. Where Bloch’s work was composed in Europe but premiered in the U.S., Dvořák’s score was composed mainly in New York during the composer’s time in America, but its ending was revised slightly when Dvořák returned home to Prague, and the work was premiered in London. Why that particular polarity of place of composition vs. place of first performance makes Bloch’s Schelomo and Dvořák’s concerto birds of a feather I’m not sure, but they do make satisfying discmates.

Unfortunately, I wish satisfying was a word I could use to describe the performances or say that they merit the excellent program note and recording afforded them, but compared to the many outstanding contenders in both works, these hardly rise above the mediocre. In much of the technically difficult passagework, cellist Marc Coppey sounds labored, and even in relaxed moments of lyrical calm his tone, which is a bit on the grainy side to begin with, is not the loveliest I’ve heard. But Coppey’s technical and tonal shortcomings are minor beside Kirill Karabits’s lackadaisical conducting and the German Symphony Orchestra Berlin’s lapses in good behavior. The orchestra’s horns, it seems, have a problem sustaining notes of any significant duration without wavering, and their intonation in places is suspect as well. On top of that, there’s some lack of coordination both between and within sections of the orchestra in all-out ensemble passages, as towards the end of the first movement of the Dvořák. It makes for a somewhat muddy-sounding melee, which I attribute to Karabits’s inattention to detail and discipline. These are not works that play themselves without strong leadership from the podium. Previous reviews of Karabits in these pages have been generally quite positive, but I notice that they are all with the Bournemouth Symphony Orchestra, the ensemble he has led as principal conductor since 2009. This, as far as I know, is his first and only recording with the Berlin-based German Symphony Orchestra, so maybe this was a case of conductor and musicians getting to know each other.

Someone once quipped about lawyers that there are so many of them if you laid them out end to end it would be a good thing. I don’t know that it would necessarily be a good thing if you laid out all the recordings of Dvořák’s B-Minor Cello Concerto end to end, but I do know there are so many of them it would make for a fairly long walk to get to the front of the line. And who would you find when you got there? Well, that’s debatable, but I’m pretty sure it wouldn’t be Coppey and Karabits.

As for Schelomo, the line isn’t nearly as long, so it’s a bit easier to pick a leader among the pack. Apart from Zara Nelsova’s classic efforts with Abravanel and Ansermet, I very much liked Truls Mørk’s performance when I reviewed it in 28:6. I felt that he gave us a portrait of an older and wiser Solomon than the one who had a youthful dalliance with the Queen of Sheba. But I also still find the version by Steven Isserlis with Richard Hickox and the London Symphony Orchestra compelling. I don’t think this effort by Marc Coppey and Kirill Karabits earns a place at the head of the line for either the Bloch or the Dvořák.

Diapason | Oktober 2017 | Jean-Michel Molkhou | October 1, 2017

Par son esprit incantatoire, sa profondeur méditative, ses couleurs orientales, Schelomo (1916) reste une des pages les plus révélatrices duMehr lesen

Marc Coppey en délivre une lecture d'une forte intériorité, dont la pudeur nous touche profondément. La voix de son Goffriller transmet toute sa tendresse, tandis que Kirill Karabits équilibre magnificence et retenue – il ne semble jamais contraindre le soliste. L'essence rhapsodique de l'oeuvre tout comme sa gravité dramatique sont traduits avec un art qui apparente la nouvelle gravure au légendaire 78 tours d'Emanuel Feuermann et Stokowski, en 1940.

Dans le concerto de Dvorak, n'attendez pas l'opulence d'un Rostropovich. Coppey, qui fut un temps le violoncelliste du Quatuor Ysaye, dialogue en fin chambriste avec les musiciens du DSO Berlin. Soliste et orchestre ne se livrent pas l'habituelle joute héroïque qui anime la plupart des versions. La baguette de Kirill Karabits sculpte en finesse les timbres de l'excellente formation berlinoise. Ici le pathétisme reste élégant. Le soin apporté aux couleurs, aux nuances, aux respirations, aux enchaînements est souligné par une prise de son sans réverbération artificielle.

Entre les deux monuments, Klid (Le Silence de la forêt), transcription par Dvorak lui-même d'une page pour piano à quatre mains, confirme le raffinement d'un disque inspiré.

Fanfare | October 2017 | Steven Kruger | October 1, 2017 | source: http://www.fanfa...

Cellists come in three general varieties, I often think: lugubrious, slithery, or chaste. Lugubrious cellists wrestle their instruments with bearMehr lesen

It’s hard to recall Ernest Bloch was once a popular Swiss/American Jewish composer. Bloch held grandiose convictions about his talents and what we’d call his DNA, and thought himself the inner source of a future Hebraic musical style for Palestine. Later becoming an American immigrant, Bloch was convinced he could replace the U.S. national anthem with his rhapsody America. He failed to do either. But he did certainly anticipate Cecil B. DeMille.

These days we’re lucky to hear Baal Shem or run into a chamber orchestra performing one of the two concerti grossi. But listen with care to Schelomo, written in 1916, and you encounter influences others picked up from him, a sure sign of how seriously Bloch was once taken. In fact, ask me quickly what Schelomo sounds like, and I’m tempted to say “Jewish Respighi.” There’s an ostinato melody for two bassoons which Bloch uses as contrast in the middle of the piece. It’s a Jewish childhood tune his mother used to sing. Start humming and you can imagine how easily it might evoke a few years later the pulsating grandeur of catacombs in Respighi’s The Pines of Rome. There are several massive climaxes in Schelomo. One of them winds down in a manner suggestive of the first movement of the Shostakovich Fifth Symphony, written decades later. So everyone was certainly paying attention, it would seem.

And well they should, here. This is the first fully hysteria-free interpretation I’ve heard. Schelomo, the cello’s voice, represents biblical King Solomon, and Bloch’s music portrays the crashing of Solomon’s world through vanity. Bloch witnessed the same thing happening to the Europe he knew, then busy slaughtering itself in World War I—message enough. But ever since World War II, you get the impression that Schelomo must have been about the Holocaust (which it could not have anticipated), and it’s usually played for fingernail-edged intensity and glass-shattering anxiety. Munch and Piatigorsky nearly burn a hole in the stage with their classic 1950s rendition. Not here: This performance is so refined and beautiful, it could nearly be Fauré. Kirill Karabits and Marc Coppey are very much on the same page, with little agogic rubato and everything smoothly dovetailed. For the first time, I really like Schelomo as music, not message.

Coppey and Karabits’s refined approach leads to a different sort of Dvořák Cello Concerto than we often hear, of course, a touch understated. An interesting comparison is to be had with a CD released by the Deutsches SO three years ago for BIS, with cellist Christian Poltéra and Thomas Dausgaard conducting. Dausgaard is an original, intuitive musician who has a remarkable way of bouncing forward and finding flecks of light in inner voices. And Poltéra is an impassioned cellist who “slithers.” The Deutsches Symphony plays beautifully for both conductors, but you can guess I find Dausgaard more exciting. Nonetheless, Coppey keeps growing on one here. And Karabits achieves a kind of temperamental perfection. We have quite a wonderful release before us, when all is said and done, and the lyrical, gentle Silent Woods is just the right sort of complement from Dvořák’s pen to Marc Coppey’s more chaste instincts. Audite’s sound is as good as BIS’s, but with the cello presented slightly more forward. It amuses me to note what must be the principal French horn in both performances play his big first movement solo with very un-German vibrato, but with no harm done. Be sure to hear this.

Fanfare | October 2017 | Huntley Dent | October 1, 2017 | source: http://dev.fanfa...

The standard repertoire for cello and orchestra doesn’t contain many French works, but the French performing style has a strong profile. I wasMehr lesen

Because it borders on the fulsome, the music tempts cellists to overplay their part and sink into sentimentality or to sound rhetorically profound. Coppey avoids both pitfalls, finding genuine eloquence through a natural approach to the score’s emotionality. Not recognizing the cellist’s name, I looked online and found that Coppey was born in 1969, won a major Bach competition at 18, and soon found himself in the company of two luminaries, Yehudi Menuhin and Mstislav Rostropovich. His schooling took place in Strasbourg, Paris, and Bloomington. His biography mentions wider interests as a singer, pianist, and composer. Fanfare readers are most likely to associate Coppey’s name with the Ysaÿe Quartet, where he was a member from 1995 to 2000.

Being ubiquitous, the Dvořák Cello Concerto has been the vehicle for a kaleidoscope of styles; my taste runs to the grand, passionate, and personal style of Rostropovich and du Pré. The fairly low-key conducting of Kirill Karabits in the first-movement introduction makes clear that this isn’t his way, so Coppey’s first entrance, which is more florid and simply loud (thanks to very close miking) isn’t quite in sync. Using a focused and beautiful tone, especially in the upper register, the soloist grabs one’s attention as the dominant force in the performance. Conductor and cellist agree that the lyrical second theme in the first movement should be delicate and gentle. I was also impressed at how even Coppey’s tone is from top to bottom, and how good his intonation is. He doesn’t dig in for a big sound in his low notes but prefers a supple, uniform timbre.

There’s an impressive musicality about everything here. I was reminded of my most recent encounter with the Dvořák Concerto, from Christian Poltéra, Thomas Dausgaard, and the same Deutsches Symphony Berlin as on the present release (reviewed in Fanfare 40:1). That was a very memorable reading, but Coppey and Karabits give nothing away to it for vigor, expression, and musicality. The Adagio gains added eloquence by being a little quieter than usual, as in the Bloch. The finale is lean, propulsive, and exciting. What more can we ask?

As a filler we get Klid, a meditative piece for piano duet that Dvořák later arranged for cello and piano before orchestrating it. Better known as Silent Woods, it is the slow movement of a four-part suite titled From the Bohemian Forest. The music was new to me, but its six minutes is based on a lovely, flowing theme, as you’d expect from one of music’s great melodists. Coppey performs with rapt sensitivity.

Given so much to appreciate and nothing to criticize, this release deserves a warm welcome. I’m motivated to seek out everything this exceptional cellist has recorded previously, including the Bach suites from 2003.

Fono Forum | September 2017 | Christoph Vratz | September 1, 2017

Als reziproke Spiegelbilder versteht der Straßburger Cellist Marc Coppey die beiden zentralen Werke seiner neuen Aufnahme: Blochs "Schelomo" entstandMehr lesen

Mehr als 20 Minuten dauert Blochs "Hebräische Rhapsodie", deren Charakter ständigem Wandel unterzogen ist. Man möchte Coppey daher gratulieren, dass er nicht ständig seine cellistische Bravour ausstellt. Dann nämlich gerät dieses Werk schnell zu einer One-Instrument-Show. Klar, das Cello steht im Fokus, ihm wird eine Vielzahl von Sprecharten abverlangt, doch Coppey geht mit dieser Luxus-Situation um wie ein Kammermusiker, der um die Bedeutung seiner Partner genau weiß. Insofern bilden Solist und das Deutsche Symphonie-Orchester Berlin unter Kirill Karabits eine Einheit.

Coppey geht es nicht um die Demonstration solistischer Überlegenheit, er lässt sein Cello nicht schmachten und meidet auch jede stratosphärische Brillanz. Genau das macht die Stärke seines Spiels aus: Es wirkt ehrlich und sehr plastisch, vor allem stellt es die Wandlungsfähigkeit seines Instruments, eines Goffriller von 1711, unter Beweis.

Beim Dvorak-Konzert ist die diskografische Spitze noch dichter beisammen, doch vom Aufnahme-Erbe lässt sich Coppey nicht beeindrucken. Allenfalls lässt er ein bisschen die Fournier-Linie durchschimmern. Noblesse und Diskretion schwingen mit, Melancholie, und wenn es expressiv sein soll, dann nie vordergründig. Coppey erzeugt einen glanzvollen, runden Ton, schlank wo möglich, breit wo nötig. Ihm geht es nicht darum, die furiosen Passagen im Lichte der Raffinesse darzustellen. Die Musik soll durch sich selbst sprechen, nicht durch Eigenheiten des Interpreten. Auch darin sind ihm die Berliner und Karabits ebenbürtige Partner. Eine herrlich unspektakuläre Aufnahme.

allmusic.com | 29.08.2017 | James Manheim | August 29, 2017 | source: http://www.allmu...

Coppey offers a full-blooded, passionate reading [...] It's a virtuoso performance with fine coordination between orchestra and soloist. Highly recommended.Mehr lesen

Audiophile Audition | August 17, 2017 | Gary Lemco | August 17, 2017 | source: http://www.audau... Marc Coppey and Kirill Karabits collaborate in two epic cello scores with singular passion

Coppey and Karabits address this movement with a singularly epic relish, grand in scope and deep in feeling, well befitting the extraordinary richness of this concerto masterpiece.Mehr lesen

www.pizzicato.lu | 09/08/2017 | Guy Engels | August 9, 2017 | source: https://www.pizz... Ein charismatischer Musiker

Nachdem Marc Coppey uns vor einem Jahr mit seinem Farbenrausch in den Cellokonzerten von C.Ph.E. Bach begeistert hat, legt der Cellist jetzt mit derMehr lesen

Mit dem Deutschen Symphonieorchester Berlin hat Marc Coppey einen nicht minder ausdrucksstarken Partner zur Seite. In Blochs ‘Schelomo’ treibt Kirill Karabits sein Orchester zu einem kraft- und spannungsvollen Spiel an – ein herrlicher Gegenpart zu den Monologen, den intimen Gedanken des Cellos.

Auch in Dvoraks Cellokonzert wartet das Orchester mit einem frischen, knackigen Klang auf. Marc Coppey lässt sein Cello in den Ecksätzen wuchtig, virtuos und schwelgerisch singen. Im Adagio hingegen lässt er die Welt vergessen. Die Musik kommt aus tiefstem Inneren von einem sehr charismatischen Interpreten: Eine der wahrhaftigsten Interpretationen dieses Concertos, die wir in letzter Zeit gehört haben.

Marc Coppey’s performances of Bloch’s Schelomo and Dvorak’s Cello Concerto are absolutely striking, both technically and expressively. Conducted by the very inspired Kirill Karabits, the Deutsches Symphonie-Orchester Berlin is an excellent partner for the French cellist.

Gramophone | 08/2017 | Rob Cowan | August 1, 2017 | source: https://www.gram...

While not wishing to mislead with excessive praise, Marc Coppey’s 2016 account of the Dvořák Concerto more reminded me of Emanuel Feuermann’sMehr lesen

Coppey’s first entry (3'28") suggests unflappable confidence and when the music takes flight soon afterwards he employs a keen-edged staccato while retaining his characteristic rich body of tone. Also, Coppey’s approach exploits the instrument’s entire range with ease: the lovely second subject is as gently seductive as the more assertive passages are bracing. Try the perfect diminuendo at 1'36" into the Adagio: this sort of playing has me reaching for the rewind facility just for the pleasure of enjoying it a second or third time. Other cellists, most notably Casals and Fournier weave their own magic but, as of yet, their younger equivalents have not appeared. Those of Coppey’s rivals who have justifiable claims on our attentions include the impassioned and tonally varied Alisa Weilerstein but there is something about Coppey’s aching restraint (if that doesn’t seem too contradictory a term) that even after such a brief period of acquaintance has had me return to his version on a number of occasions. So far the magic hasn’t abated.

Bloch’s Schelomo was another Feuermann staple but although Coppey again hits target, he’s pipped to the post, in the stereo field at least, by the superb Feuermann pupil George Neikrug, who, like his master, is granted an incendiary account of the orchestral score under Leopold Stokowski. Kirill Karabits and his Berlin forces, good as they are (and of course better recorded), don’t quite match that level of intensity, whereas they provide sensitive and detailed accounts of the two Dvořák scores – Silent Woods is no less effective than the concerto – which adds further credence to an extremely strong recommendation.

www.highresaudio.com | 27.07.2017 | July 27, 2017 | source: https://www.high...

The excellent recording technique this album has been created, is customary practice for audite and it is particularly effective in the form of the present high-resolution download.Mehr lesen

Sunday Times | 2nd July 2017 | Stephen Pettitt | July 2, 2017

Coppey brings to Schelomo — Ernest Bloch’s dark-hued evocation of theMehr lesen

www.pizzicato.lu | 30/06/2017 | Remy Franck | June 30, 2017 | source: https://www.pizz... Exzeptionell, in allen Hinsichten

Nur ganz selten habe ich Ernest Blochs ‘Schelomo’ in einer so stimmungsvollen, hoch inspirierten Fassung gehört wie auf dieser neuen CD mit demMehr lesen

In ‘Schelomo’ (Salomon), das Bloch selbst eine ‘Rhapsodie hébraïque pour violoncelle et grand orchestre’ (1916-17) nannte, übernimmt das Cello den Part des weisen Königs mit einer teils melancholischen, teils feierlichen Klangrede: Coppey ‘singt’ diesen Part auf seinem Goffriller-Cello mit bewegender Intensität, nicht vordergründig sentimental, aber mit einer wunderbar vergeistigten Vertiefung in das Sujet. Dabei kann er voll auf den Dirigenten Kirill Karabits zählen, der den Cello-Gesang mit einem sehr inspirierten Orchester unterstützt. Karabits, einer der besten Farbenkünstler unter den Dirigenten, lässt das DSO mit schönster Differenzierung musizieren.

Dvoraks kurzes, sehr charmant und ausdrucksvoll gespieltes Adagio ‘Klid’ (Waldesruhe) führt zum Cellokonzert op. 104.

Was einem in diesem Werk sofort auffällt, ist die ungemein reliefreiche Orchestereinleitung, die zeigt, welch genialer Dirigent Karabits ist. Die einzelnen Motive werden sehr deutlich herausgearbeitet, die verschiedenen Orchestergruppen in grandiosen Farben voneinander abgehoben. Und so sind die Weichen hier ganz klar gestellt. Mehr als in irgendeiner Aufnahme des Dvorak-Konzerts spielt das Orchester hier eine wichtige, eine tragende Rolle. Dass Karabits für diese Aufnahme gewonnen werden konnte ist ein absoluter Glücksfall. Nicht, dass Coppey nicht gut spielen würde, ganz im Gegenteil, aber sein Spiel erreicht erst im Einklang mit dem Orchester seine volle Wirkung.

Es gibt Aufnahmen, da hat man nach einem einzigen Durchgang alles gehört. Diese hier ist musikalisch so reich, dass man davor steht wie vor dem üppigsten aller Buffets und sich mal hier, mal dort was nimmt, aber bei weiteren Durchgängen immer wieder Neues entdeckt.

Darüber hinaus ist auch das wunderbar lyrische und zugleich oft auch zupackende Spiel von Marc Coppey ein Atout, zumal Dirigent und Solist perfekt zusammen atmen.

This is one really outstanding recording, perfect for multiple deep listening experiences. Bloch’s Schelomo comes in a very inspired, beautifully atmospheric performance, and one only can admire Marc Coppey’s attractive, lyrical sound. Another exceptional treat is Dvorak’s Cello Concerto. Breathing harmoniously together, conductor Kirill Karabits and Marc Coppey share a perfect mutual inspiration. Moreover, Kirill Karabits proves the colour magician he has always been, and thus there is a lot to discover in the orchestral accompaniment. I never heard so rich an orchestral playing in this concerto. The well-detailed, resonant recording adds to the impact of those gorgeous Bloch and Dvorak performances.

www.myclassicalnotes.com | June 23, 2017 | June 23, 2017 | source: http://www.mycla... Dvorak Cello Concerto by Marc Coppey

Antonín Dvořák and Ernest Bloch provide clear performing instructions, but also demand a high degree of free interpretation. Marc Coppey manages to realize both of these aspects, maintaining a convincing balance and communicating intensively with the orchestra.Mehr lesen

www.artalinna.com | 5 August 2017 | Jean-Charles Hoffelé | source: http://www.artal... Le Graal du Violoncelle

[Marc Coppey] s’engage dans l’œuvre avec une intensité, une furia, quelque chose de précipité et de quasiment à court de souffle qui dès les premières pages saisit.Mehr lesen