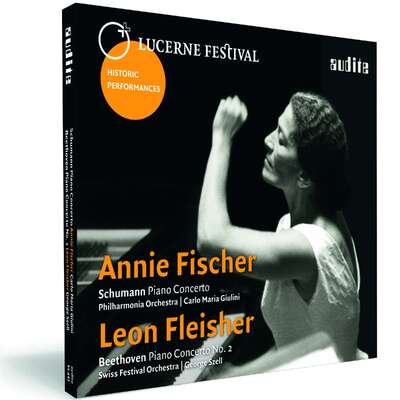

Two pearls of pianism: Annie Fischer in a sensitive, chamber-like and exceptionally poetic reading of the Schumann Piano Concerto – one of her favourite pieces. Leon Fleisher, a few months before he was to lose the use of his right hand (recovering it only in old age), with Beethoven’s Second Piano Concerto in an inspirationally bright and crystal clear tone.more

"Here we have a real collector’s item, with excellent performances, remarkable above all for the congenial interpretations by two outstanding soloists and two exceptional conductors." (Pizzicato)

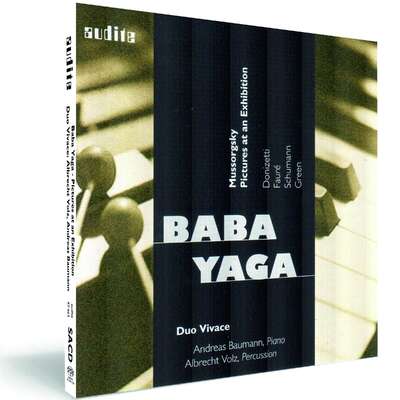

Details

|

Annie Fischer plays Schumann: Piano Concerto, Op. 54 - Leon Fleisher plays Beethoven: Piano Concerto No. 2

LUCERNE FESTIVAL Historic Performances, Vol. 8 |

|

| article number: | 95.643 |

|---|---|

| EAN barcode: | 4022143956439 |

| price group: | BCB |

| release date: | 16. October 2015 |

| total time: | 60 min. |

Bonus Material

Informationen

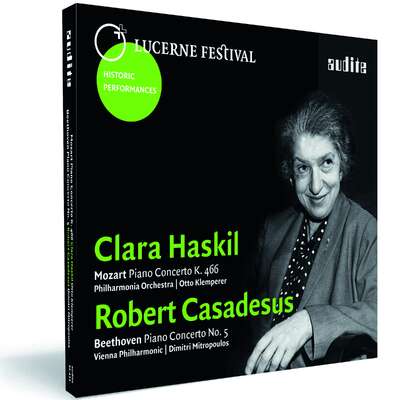

The eighth disc in the series "LUCERNE FESTIVAL Historic Performances" is dedicated to two piano icons: in 1960 and 1962, with two years between them, Hungarian-born Annie Fischer and the American Leon Fleisher made their debuts at LUCERNE FESTIVAL. Released here for the first time in their entirety, these live recordings document them at the peak of their art.

Sviatoslav Richter called her a "brilliant musician", accrediting her with "great breath and true depth". András Schiff acknowledged: "I have never heard more poetic playing in my life." Annie Fischer, born in Budapest in 1914, gave public performances even as a child, winning the International Liszt Competition in 1930 and after that, except during the war, touring worldwide. Nonetheless, she tends to be rated as an insider's tip, not least because she left behind only a handful of studio recordings. That makes live recordings such as this, released for the first time, all the more precious: at her only performance in Lucerne in summer 1960, Annie Fischer realised a sensitive, chamber-like and exceptionally poetic reading of the Schumann Piano Concerto with which she "garnered unusually fervent success", according to the Neue Zürcher Zeitung. She found congenial musical partners in Carlo Maria Giulini and the Philharmonia Orchestra.

Leon Fleisher made his Lucerne debut in 1962 at the age of thirty-four: on the peak of his rapid career which had - as had been the case with Annie Fischer - catapulted him into musical life while he was still a child. However, only a few months after his Lucerne performance - released for the first time in its entirety - he developed "focal dystonia", making the use of his right hand impossible. During the following decades, Fleisher became a specialist of the left-handed repertoire until, in his old age, he was once again able to play with both hands, thanks to new medical treatments. In Lucerne, he presented himself with one of his party pieces - Beethoven's Second Piano Concerto, which he played with an elegant and transparent tone. The Swiss Festival Orchestra was conducted by George Szell, with whom he had made a studio recording of the concerto one year previously - an interesting comparison. The second half of this concert, Brahms' First Symphony, is already available in this series of "LUCERNE FESTIVAL Historic Performances" and has been awarded the "Diapason d'Or" as well as a nomination for the International Classical Music Awards (ICMA).

The 32-page booklet in three languages provides extensive background information on Annie Fischer and Leon Fleisher, and also features photos from the festival archives of all artists involved, published here for the very first time.

In cooperation with audite, LUCERNE FESTIVAL presents outstanding concert recordings of artists who have shaped the festival throughout its history. The aim of this CD edition is to rediscover treasures - most of which have not been released previously - from the first six decades of the festival, which was founded in 1938 with a special gala concert conducted by Arturo Toscanini. These recordings have been made available by the archives of SRF Swiss Radio and Television, which has broadcast the Lucerne concerts from the outset. Painstakingly re-mastered and supplemented with photos and materials from the LUCERNE FESTIVAL archive, they represent a sonic history of the festival.

Reviews

International Piano | May / June 2016 | Benjamin Ivry | May 1, 2016 No laughing matter

‘Playing’ the piano never seems quite the right way of describing Annie Fischer at the keyboard. Sober, serious and uncompromising are the heroicMehr lesen

In a typically thrilling concert performance from late in her career, a septuagenarian Annie Fischer played Beethoven’s Third Piano Concerto with the NHK Symphony conducted by Miltiades Caridis. In the 1989 video, the granitic Hungarian grandma laid down the law with uncompromising grandeur. One thinks of Irene Worth, the American actress long resident in the UK, whose tough-as-nails, omniscient Grandma Kurnitz in Neil Simon’s film Lost in Yonkers moved audiences.

Beyond such matriarchal flamboyance and energy, Fischer’s performances were noted for their intense idiomatic understanding and devil-may-care absolutism, despite wrong notes. Her inspiration derived from the era of Artur Schnabel, during which the musical message was primordial, not the note-for-note perfection expected from studio recordings. There was something sublime in the sheer limpidity of her best solo work, as in a Brahms Sonata in F minor (on BBC Legends 4054-2), recorded at Edinburgh’s Usher Hall in 1961. Yet in Fischer’s renditions, especially from her later years, there can be a noteworthy absence of merriment or festivity in some of the more playful or witty passages, for example in Beethoven and Mozart. This unrelentingly tragic approach sometimes fails to express an inherent element in the music. Fischer laboured heroically at the keyboard; she did not ‘play’ the piano. Any mere ludic aspiration might be too trivial for an artist of such high seriousness.

On the other hand, she often conveys a take-no-prisoners attitude, as in a Schumann Kreisleriana from 1986 (BBC Legends 4141). Conquering this score seems akin to scaling an Alpine peak unaided. Sombre and sober, she boldly plumbed emotional depths of the most demanding Classical and Romantic scores. Her Mozart concertos, especially in the 1980s, could have tragic weight bordering on ponderousness. Yet this is vastly preferable to the superficial, fleetfingered gloss with which these works are sometimes dispatched.

After hearing her dense 1968 studio recording of Schubert’s Sonata in B-flat D960 (reissued on Hungaroton 41011) one might wish to call for ‘More light!’ (as Johann Wolfgang von Goethe reportedly did on the occasion of his last gasp). Even the gossamer and celebratory final two movements of Schubert’s D960, marked Scherzo allegro vivace con delicatezza and Allegro, ma non troppo, express disquiet and adamant feelings in Fischer’s weighty hands. This is even more evident in a somewhat lumbering traversal, marred by technical hiccups, of Schubert’s Sonata No 20 D959 from a 1984 Montreal recital (on Palexa CD-0514). Still, the overall integrity and cohesiveness of Fischer’s performances renders such quibbles relatively meaningless.

No such qualms impede our appreciation of her best recordings, such as a handful of versions of Beethoven Third Concerto. On one of these from 1957, with the Bavarian State Orchestra led by Ferenc Fricsay (available on Pristine Audio PASC400), the vivacity of soloist and accompanying orchestra are ideally matched, driving the performance along with vigorous momentum. In a live Mozart Piano Concerto No 22 K482 from 1956 with Otto Klemperer (Palexa 515), or No 23 K488 with the Philharmonia and Adrian Boult (Documents 299267), courtly accompanists fluent in the Mozartian idiom proved apt interlocutors.

Among many intriguing recordings of one of her warhorses – Schumann’s Piano Concerto in A minor – a high place must be granted to a live performance from Lucerne with the Philharmonia and Carlo Maria Giulini (on Audite 95643). Then there is a pellucid studio Bartók Third Concerto from 1955 with Igor Markevitch (Warner Classics 68733); atypically effervescent Mozart concertos from the 1950s with the Concertgebouw Orchestra and Otto Klemperer (Archiphon ARC-WU099-100); and a fizzy Beethoven Third Concerto from 1956, again with the Concertgebouw and Klemperer (Archiphon ARC-WU092-93). The impression of an endless treasure trove of artistically rewarding recordings is accurate: Annie Fischer’s discography really is that rich.

Fischer’s solo work is equally lively, in such mainstays as Beethoven’s Pathétique Sonata (an ideal 1958 studio version reissued on Warner Classics 634123). The scale and architectural scope of her conception of Beethoven sonatas makes even her later complete set, with its highs and lows (Hungaroton 41003) worthy of sustained attention. A 1960s video, about which less-than-precise information exists, features Fischer playing the Pathétique in Budapest’s Great Hall of the Franz Liszt Academy of Music. At times her tempi are so fast as to suggest she feared being hustled off the stage for not finishing promptly. A less enchanting experience are two-ton, sometimes lurching 1970s studio renditions of late Beethoven that sound ungainly. In their own way, even these flawed performances by Fischer are as daringly individual as Schnabel’s, though ultimately less convincing – at least to some listeners.

Fischer needed no Polonius to know how to be true to herself. It seems apt that she died while listening to a radio broadcast of Bach’s St John Passion. A large-scale, emotive reading of Bach’s Brandenburg Concerto No 5 with Otto Klemperer from 1950 (Guild GHCD 2360) is further evidence of her devotion to this composer, and collegial rapport with this tricky conductor.

Where did this acute artistry develop? Fischer studied at Budapest’s Franz Liszt Academy with the pianist and composer Ernő Dohnányi (1877–1960) and the pedagogue Arnold Székely (1874-1958). The latter also taught Andor Földes, Louis Kentner, Lívia Rév, and Georg Solti. In 1933, still in her teens, Fischer won the first Franz Liszt International Piano Competition, a contest in which Louis (born Lajos) Kentner was placed third and Andor Földes eighth. Relatively early in her career, she was performing and learning from such celebrated maestros as Ernest Ansermet, Adrian Boult, Fritz Busch and Willem Mengelberg. Starting in the 1950s, she made studio recordings with some excellent conductors, including Fricsay and Markevitch, but some of Fischer’s finest surviving performances with orchestra have yet to be transferred to CD. An online discography by Yuan Huang* includes enticing items such as a Bartók Third Concerto from 1955 led by the eminent Hungarian conductor László Somogyi. There also survives a 1963 Beethoven Emperor Concerto from Russia, led by the Latvian maestro Arvīds Jansons (father of Mariss Jansons); a 1970 Brahms Second Concerto with Christoph von Dohnányi; and a 1972 Beethoven Fourth Concerto conducted by Ernest Bour. If and when these performances become more widely available, a fuller impression of the range and scope of Fischer’s artistic achievement will become possible.

For now, the inner mysteries of Fischer’s profound artistry may be revealed in part by a surviving 1992 rehearsal fi lm of Mozart’s Concerto No 22 K482. Fischer wears a headscarf and, during the orchestral tuttis, puff s on a cigarette stashed in an ashtray inside the piano. The conductor Tamás Vásáry, himself a noted pianist, looks at her with justified veneration; indeed he saw her as a mentor, as did another veteran Hungarian keyboard master of today, Peter Frankl. When Fischer’s fingers are otherwise unengaged, she conducts with her left hand for a few instants, then remembers the smouldering cigarette conveniently stashed inside the piano. She reaches for it with her right hand and takes a drag, savouring what are clearly twin necessities in life: Mozart and nicotine. Then she conducts along a little with her right hand, using the cigarette as a tiny baton, inhaling repeatedly before replacing the ciggie in its ashtray just before the next keyboard passage.

The Romanian-French aphorist Emil Cioran, himself an ex-tobacco aficionado, once proclaimed that during his smoking days, he ‘could not even appreciate a landscape without a cigarette in his hand’. Likewise, Fischer was an artist whose life and work were intertwined with smoking. That said, to apply the joshing sobriquet ‘Ashtray Annie’ to Fischer, as London’s orchestral musicians reputedly did during her lifetime, trivialises the passion she invested in all her activities, whether for music or self-administering jolts of nicotine.

Tobacco deprivation in concert halls may possibly have resulted in the peremptory, nervy attack that mars some of Fischer’s live performances, especially of Beethoven. Life struggles also doubtless affected her world view. During the Second World War, Fischer fled her homeland to Sweden with her husband, the musicologist Aladár Tóth (1898-1968). She was born Jewish, and 70 percent of Hungary’s Jews (an estimated 450,000 of them) were murdered by the Nazis. Despite this carnage, Fischer returned to Budapest after the war, and stayed through successive Communist dictatorships. This wartime exile and impoverished life in the postwar Soviet bloc may explain a certain bleak outlook compatible with a tragic view of art and life.

With fanfare on her centenary in 2014, the Hungarian government issued a postal stamp in Fischer’s honour. This may seem ironic to some observers, given the re-emergence in Hungary of far-right politicians and their hateful antisemitic rhetoric. To the piano world, Hungary is now the place where Budapest-born András Schiff dares not return for a visit because if he does so, his compatriots have threatened to ‘cut off both of [his] hands,’ as Schiff told the BBC. Official state celebrations of Annie Fischer in Hungary have not mentioned her Judaism.

Genuine honour to Fischer comes from the world’s piano lovers. During her lifetime she received justified praise from critics such as Andrew Keener, who in the July 1983 Musical Times commended Fischer’s London recital for ‘musicmaking that radiated humanity, humour and an abundant sense of enjoyment. Rarely can momentary aberrations have mattered so little and never once was there any suspicion that faulty technique was responsible. Over and again, notably in the second and fourth movements of Beethoven’s Sonata Op 101, exuberantly characterised, Annie Fischer would follow a momentary sketchiness with something technically remarkable by any standards’. Keener’s inclusion of humour as a feature of her playing may indicate that on occasion the aforementioned caveat about uniform seriousness may be overstated.

Even Charles Rosen, the American pianist who could be hypercritical about colleagues, wrote aff ectionately in his Piano Notes: the World of the Pianist (2002) about sitting on the jury of the 1966 Leeds Competition with Fischer (other jurors included Gina Bachauer, Maria Curcio, Rudolf Firkušný, Nikita Magaloff and Lev Oborin). Rosen lauded Fischer as a ‘pianist for whom I (like almost everybody else) had the utmost admiration, who gave a good mark to the pianist I thought should get another chance; she was rather taken with a good-looking Korean contestant, so I voted for her candidate and she voted for mine. In the next round, I was sitting next to her while the Korean was playing, and she turned to me and said softly: “He isn’t very good, is he?” – “No,” I replied, trying to invest my reply with the proper melancholy.’

Just as some operatic divas and divos show their mettle best in live recordings, so Fischer seemed to exult in the drama and electricity of a performance in the presence of an audience, rather than an antiseptic, Apollonian recording studio. Even today, responding to the energetic physicality of her playing, some critics who are unaware of the evolution of gender politics refer to Fischer’s ‘masculine’ style. What they simply mean is that she was one of the mightiest pianists of her century.

American Record Guide | May / June 2016 | Alan Becker | May 1, 2016

Many will be familiar with Fischer’s 1960 studio recording of the Schumann with Klemperer. This one with Giulini dates from the same year and comesMehr lesen

Fleisher’s way with the Beethoven is already well known from the studio set with Szell and the Cleveland Orchestra. That set is one of the marvels of Beethoven performance and has a recording that leaves nothing to be desired. This Beethoven 2 is similar, though few could make claims for its supremacy as an orchestral recording. The ad hoc ensemble plays well for Szell, and the piano sound here is quite good.

Could I recommend purchase of this recording? Well, yes and no. It is certainly a must for admirers of these artists who must have every recording they ever made. No if you already have the studio recordings. Still, I was seduced once again by Fleisher’s marvelous playing.

Fanfare | April 2016 | Huntley Dent | April 1, 2016

Two illustrious pianists with star-crossed careers are honored here, and acquit themselves with honor. The eminent Hungarian pianist Annie FischerMehr lesen

Her playing is so adroit and natural—to the point of sounding effortless—that one easily believes Schumann was one of Fischer’s favorite composers. Her well-balanced interpretation flows in perfect accord with Giulini, who included among his talents the skills of a great accompanist. The Philharmonia, honed by Karajan since its founding, plays with a lovely, rounded tone. Perhaps the finale is a bit too relaxed and self-contained to fit Schumann’s marking of Allegro vivace, but this is a flawless reading in which cultivation and Romanticism are beautifully merged. Fischer is still undervalued outside Hungary, and this live performance is a major addition to her discography.

Leon Fleisher’s fate was to lose the use of the last two fingers of his right hand only months after this appearance at the Lucerne Festival in the summer of 1962 (the highly unreliable program notes attribute the onset of paralysis to a condition called “pianist’s neurosis”—let’s hope something was lost going from German to English). He was one of the brightest lights among post-war American pianists, and even though Fleisher was a pupil of Artur Schnabel’s, he approaches the Beethoven Second Piano Concerto with the cool, crystalline touch of Horowitz, who had a profound effect on that entire generation. The passagework is stunning, not just for clarity but also for the nuance Fleisher adds even when moving at top speed. His complete Beethoven concerto cycle with Szell has never left the catalog since the early 1960s, and on this occasion they remain aligned in preferring a fleet, Haydnesque approach, albeit with a fairly robust-sounding orchestra; there is minimal rubato and no slow down for second themes. The atmosphere of a live concert adds an extra touch of exuberance from both conductor and soloist.

Unlike Fischer, Fleisher returned several times to Lucerne, twice to play concertos for the left hand by Ravel and Prokofiev, then twice more, in 2008 and 2012, for solo recitals after he recovered the use of both hands. It’s worth nothing that on the second half of this 1962 concert Szell led a very fine reading of the Brahms First Symphony, previously released in Audite’s admirable series devoted to Swiss Radio broadcasts from the Lucerne Festival. Every installment to date has been warmly received by Fanfare critics.

Despite a few egregious passages, the program notes contain useful information. The recorded sound, which favors the piano considerably, is very good for a mono radio broadcast, affording a rich timbre to the instrument even if the orchestra is a bit thin and edgy, but only a bit. Artistically, the archives have yielded up two must-listen performances.

eve - ernährung | vitalität | erleben

| 2.2016 März/April | March 1, 2016

Für Klassikfreunde

Glasklare Töne

Annie Fischer mit einer kammermusikalisch hellhörigen und poetischen Deutung von Schumanns KlavierkonzertMehr lesen

Musik & Theater | 03/04 März/April 2016 | Werner Pfister | March 1, 2016 Zwei Seiten einer Medaille

[Fleisher] verzaubert mit einer feingliedrigen, leichthändigen Pianistik, als hätte er schon von den modernen Bemühungen um einen historisch authentischen, das heißt entschlackten und verschlankten Beethoven gehört. Herrlich sein jeu perle, seine luzide Artikulation und artikulatorische Wendigkeit. Dieser Beethoven war damals zweifellos ein Ereignis.Mehr lesen

Audio | 03/2016 | Andreas Lucewicz | March 1, 2016

Immer wieder bietet das Label Audite historische Trouvaillen, in diesem Fall zwei absolut hörenswerte Dokumente vom Lucerne Festival 1960: SchumannsMehr lesen

BBC Music Magazine | February 2016 | Julian Haylock | February 1, 2016

Recorded live at the Lucerne Festival in remarkably fine sound, Fischer's golden tone recalls an already bygone age, while Fleisher's dazzling clarityMehr lesen

Fono Forum | Februar 2016 | Götz Thieme | February 1, 2016 Kritiker-Umfrage 2015

Künstler für Kenner live in Luzern 1960 und 1962. Annie Fischer beispielsweise spielt mit sagenhafter Energie und Poesie.Mehr lesen

Record Geijutsu | FEB. 2016 | February 1, 2016

Japanische Rezension siehe PDF!Mehr lesen

Gramophone | February 2016 | Rob Cowan | February 1, 2016 Pianists live in Lucerne

I was delighted to encounter Audite's CD of a riveting Lucerne Festival performance of Schumann's Piano Concerto by Annie Fischer with theMehr lesen

Der Kurier | 23.12.2015 | Alexander Werner | December 23, 2015 Pianistische Höhepunkte

Reizvoll, zwei solche Pianogrößen wie Annie Fischer und Leon Fleisher auf einer neuen CD von Audite in der Reihe mit Live-Mitschnitten vom Lucerne Festival zu hören. Beeindruckend, wie frisch, klar ausgeformt und mit Poesie die 1995 verstorbene Ungarin 1960 Robert Schumanns berühmtes Klavierkonzert spielte. [...] Fleisher und Szell ziehen hörbar an einem Strang, in einer pianistisch transparent strukturierten und expressiven Deutung und einem Orchester auf Augenhöhe, das unter straffer Stabführung zügig und klassizistisch auftrumpft.Mehr lesen

Midwest Tape | 08.12.2015 | December 8, 2015

Released for the first time in their entirety, these remastered live recordings document two piano icons in their Lucerne Festival debuts.Mehr lesen

www.pizzicato.lu | 13/11/2015 | Alain Steffen | November 13, 2015 Aufregendes aus Luzern

Auch diese rezente Veröffentlichung der ‘Lucerne Festival’-Reihe von Audite lässt den Hörer an zwei aufregenden Konzertmitschnitten teilhaben.Mehr lesen

Aber auch das 2. Klavierkonzert von Beethoven mit dem Solisten Leon Fleisher gewinnt erst durch Georg Szell am Pult seine Einmaligkeit. Fleisher spielt eher dezent, fügt sich aber mit sportlich-elegantem Stil in die von Szells schnellen Tempi bestimmte Interpretation. Leider bleibt das Spiel des ‘Swiss Festival Orchestra’, das wohl kaum Szells Anforderungen gerecht wird, nur ungefähr. Trotzdem, wegen den beiden Solisten und vor allem, wegen den beiden Dirigenten ein Must für den Sammler.

Here we have a real collector’s item, with excellent performances, remarkable above all for the congenial interpretations by two outstanding soloists and two exceptional conductors.

Audiophile Audition | November 7, 2015 | Gary Lemco | November 7, 2015

Both Hungarian virtuoso Annie Fischer (1914-1995) and American pianist LeonMehr lesen

Gauchebdo

| 15 octobre 2015 | Myriam Tetaz-Gramegna | October 15, 2015

Des concerts qui ont marqué leur époque

La 9ème de Beethoven par Furtwaengler et des concertos par Annie Fischer et Leon Fleischer s'ajoutent à l'Histoire sonore du festival de Lucerne chez Audite.

Ces deux disques ouvrent des perspectives parfois inattendues sur des oeuvres qu’on croit connaître.Mehr lesen

Crescendo Magazine | Le 12 octobre 2015 | Bernadette Beyne | October 12, 2015 Deux nouvelles merveilles du Festival de Lucerne

Les tempi sont « puissants » dans le sens où ils véhiculent un grand souffle d’énergie soutenue par une pulsation rythmique en dynamique perpétuelle. Et puis, quelle sonorité ! Couleur, chatoiement, toujours expressive. Chaque moment est intensément vécu et conduit, tant musicalement qu’émotionnellement [...]Mehr lesen

natürlich - Kundenmagazin für Reformwaren und Naturkosmetik

| März 2016

Für Klassikfreunde

Glasklare Töne

Annie Fischer mit einer kammermusikalisch hellhörigen und ungemein poetischen Deutung von Schumanns KlavierkonzertMehr lesen