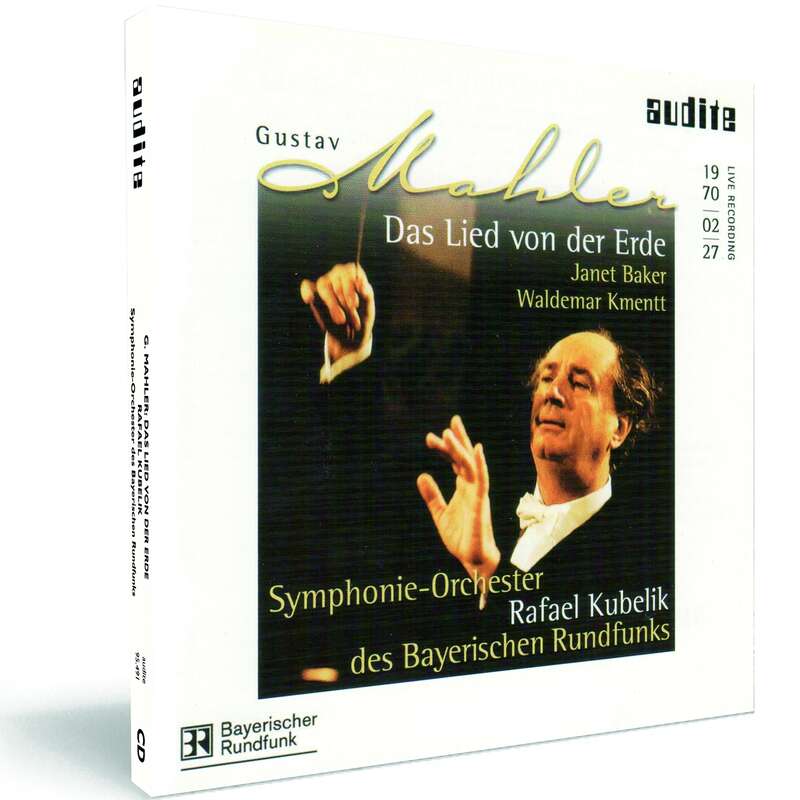

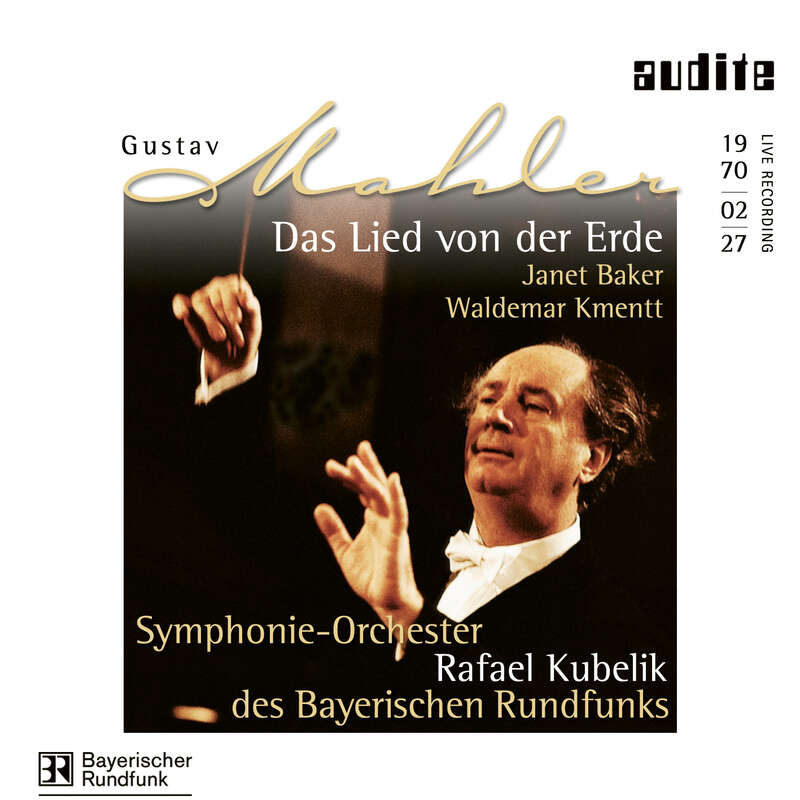

The audite Mahler cycle with Rafael Kubelik and the Bavarian Radio Symphony Orchestra contains live recordings of Gustav Mahler's Symphonies 1, 2, 3, 5, 6, 7, 8 and 9 as well as The Song of the Earth (with Janet Baker and Waldemar Kmentt).more

Rafael Kubelik

"...you won't find readings of greater warmth, humanity and patient sensitivity. That the pulse has slowed just a little is all to the good, and the more spacious sonic stage preserved by Bavarian Radio bathes the music-making in an appealing glow without serious loss of details." (Gramophone)

Track List

Multimedia

- Edith Mathis on the front cover of Fono Forum 6/1963

- "Listen & Compare" in Fono Forum 2/2005

- Franz Crass in Fono Forum 3/1962

- Rafael Kubelik in Fono Forum 6/1965

- Dietrich Fischer-Dieskau in Fono Forum 7/8/1957

- Dietrich Fischer-Dieskau in Fono Forum 6/1959

- Rafael Kubelik on the front cover of Fono Forum 7/1963

- Edith Mathis on the front cover of Fono Forum 6/1963

- Martina Arroyo in Fono Forum 3/1970

- Review in "CD maniac, classic 100CD"

- Janet Baker in Fono Forum 6/1970

Informationen

The audite Mahler cycle with Rafael Kubelik and the Bavarian Radio Symphony Orchestra contains live recordings of Gustav Mahler's Symphonies 1, 2, 3, 5, 6, 7, 8 and 9 as well as The Song of the Earth (with Janet Baker and Waldemar Kmentt).

Reviews

www.pizzicato.lu | 09/01/2026 | Remy Franck | January 9, 2026 | source: https://www.pizz... Eine essentielle Interpretation vom ‘Lied von der Erde’

Gut, dass hin und wieder an die Rolle Rafael Kubeliks in der Verbreitung der Werke Gustav Mahlers erinnert wird. Diese Aufnahme ist umso erfreulicher,Mehr lesen

So prächtig hat das Mahler-Orchester in dieser Partitur tatsächlich selten geklungen. Kubelik taucht die Musik völlig unpathetisch in ein gleißendes Licht. Das ‘Lied von der Erde’ klingt daher unerhört neu: das Orchester ist von stupender Klarheit, fast kammermusikalisch fein ziseliert, von bestechender Reinheit und ohne jede dunkeln Gedanken. Gerade dadurch wirkt Kubeliks Interpretation so anders, so neu: frei von jeglicher Sentimentalität zelebriert er keinen Trauerdienst, sondern gibt Mahlers Musik einen eher optimistischen, in die Zukunft weisenden Charakter.

Erstaunlicherweise bleibt sogar Janet Bakers Stimme hell und lichtstark, und Waldemar Kmentt – in großer Form – singt ohne Anstrengung, ohne theatralische Geste, sehr stilvoll und ohne jede störende Akzentuierung, weil er in diesem kammermusikalisch transparenten orchestralen Umfeld einen sicheren Platz hat.

Audite legt also mit dieser CD eine in der Interpretationsgeschichte vom ‘Lied von der Erde’ essentielle Interpretation vor, die unsere Sicht auf dieses von Mahler als sein persönlichstes Werk bezeichnete Komposition völlig erneuert.

------

English translation:

It is good that Rafael Kubelik’s role in promoting the works of Gustav Mahler is occasionally remembered. This recording is all the more gratifying because it gives us a ‘Lied von der Erde’ (Song of the Earth) whose expressive range and variety of colors is considerably greater than that of Kubelik’s studio recordings of Mahler’s symphonies. The Swiss-Czech conductor never recorded ‘Das Lied von der Erde’ in the studio. And such a studio recording could hardly have been better than this live recording.

The Mahler Orchestra has rarely sounded so magnificent in this score. Kubelik bathes the music in a dazzling light without any sentimentality. The ‘Song of the Earth‘ therefore sounds incredibly new: the orchestra is of stupendous clarity, almost chamber music-like in its finely chiseled detail, of captivating purity and without any dark thoughts. It is precisely this that makes Kubelik’s interpretation so different, so new: free of any sentimentality, he does not celebrate a funeral service, but gives Mahler’s music a rather optimistic, forward-looking character.

Surprisingly, even Janet Baker’s voice remains bright and luminous, and Waldemar Kmentt – in great form – sings effortlessly, without theatrical gestures, very stylishly and without any distracting accentuation, because he has a secure place in this chamber music-like, transparent orchestral environment.

With this CD, audite presents an essential interpretation in the history of interpretations of ‘Das Lied von der Erde’, which completely renews our view of this composition, described by Mahler as his most personal work.

www.amazon.de | 6. August 2019 | August 6, 2019 | source: https://www.amaz... Completely outstanding

This is now my favourite Lied von der Erde. Everything seems right: soloists just superb, orchestra wonderfully transparent, ideal recording, with theMehr lesen

www.amazon.de | 8. Mai 2019 | Derek J. Johnston | May 8, 2019 | source: https://www.amaz... Could this be the only Das Lied you'll ever need? Probably!

Please allow me to get the caveats out of the way before I say why I think this might be the only Das Lied you'll ever need: I'm very much a layMehr lesen

So why do I think this might be the only Das Lied you'll ever need? The answer is simple: intimacy. This is the only version of this piece of music I've heard that seems to have been played to and for the listener rather than at the listener. Whether that's because of how it was recorded or performed I couldn't say. Perhaps it's a combination of both. All I know is, is that when Janet Baker and Waldemar Kmentt sing, although especially when Janet is singing, I feel as though though they're singing to and for the listener, which in my case, is me. The goes for the orchestra: when they play, I feel as though they're playing to and for me.

There are probably many other recordings out there that sound better, clearer, less polluted by background noise. But I really feel that what is lost in audio quality with it being a live recording is gained in spades in musicality.

Like I say, I don't have the knowledge and experience to critique this performance from a technical point of view. I just want to confirm what others have said: that this is a genuine 5-star version of Das Lied... and probably the only one you'll ever need!

I should add, that although Herreweghe's reading (the Schoenberg-Riehn transcription) comes close in terms of that sense of intimacy, without Janet Baker on vocals, however, it just can't compete with this under-appreciated masterpiece.

ClicMag | N° 10s Novembre 2013 | Jérôme Angouillant | November 1, 2013

Deux figures légendaires de l'interprétation mahlérienne réunies à l'occasion d'un concert à Munich pour l'oeuvre peut-être la plus intime et douloureuse de Mahler: « Le chant de la terre ».Mehr lesen

Classic Collection | WEDNESDAY, DECEMBER 29, 2010 | Victor Carr | December 29, 2010

This Kubelik Mahler Two is the latest in Audite's series of live BavarianMehr lesen

Sunday Times | 5 December 2010 | David Cairns | December 5, 2010

Sunday Times classical records of the year<br /> <br /> Kubelik inspires his BavarianMehr lesen

Kubelik inspires his Bavarian

Fanfare | Issue 34:2 (Nov/Dec 2010) | Lynn René Bayley | November 1, 2010

It’s really a pity that this disc is just a reissue of a performance previously available in DGG’s set of complete Mahler symphonies conducted byMehr lesen

Being personally very fussy in regard to symphonies including singers, I’ll automatically reject performances with defective voices even if the conducting is considered to be the best ever. For this reason, I don’t own the otherwise fantastic performances by Jascha Horenstein and Klaus Tennstedt, and never will, just as I don’t own or even listen to most recordings of the Beethoven Ninth made after, say, 1980. Solti’s famous studio recording of this Mahler symphony had, perhaps, the best eight singers amassed in one place, but they were recorded separately from the orchestra, which created a flat, two-dimensional sound I find offensive. That being said, I am partial to the recordings by Leopold Stokowski (1950), Bernard Haitink (the earlier recording with Cotrubas, Harper, and Prey), and Antoni Wit, in which the defective voices are, to my ears, less annoying than in the others, and generally just one bad voice per ensemble.

The fact that Kubelík, who never pushed his name or fame and in fact retreated from a publicity machine, was able to entice these eight outstanding singers to Munich for this performance says a lot for how much he was respected as a musician. The one name not universally feted at the time was tenor Donald Grobe, and ironically he produces the finest singing of this very difficult music I’ve ever heard (James King with Solti notwithstanding). Kubelík also managed to get truly involved and exciting singing out of Martina Arroyo, and that in itself is a miracle. (He did the same with Gundula Janowitz in his studio recording of Die Meistersinger, though overall his conducting on that set, like most of his conducting in a studio environment, lacks the full power and emotional commitment of his live work). Sometimes the singers are a little off-mike, coming only out of the left or right speakers, but that’s a condition of the original microphone setup and can’t be changed.

Undoubtedly the most controversial aspect of this performance is its full-speed-ahead tempos, particularly in “Veni, Creator Spiritus,” which Kubelík dispatches in a mere 21 minutes. (Don’t believe the designation of 21:30 on the CD box; 25 seconds of that is silence with audience coughing before part II.) But, shockingly, it doesn’t sound terribly rushed most of the time, there are few dropped notes, and the whole thing has the ecstatic quality of a satori. If you happen to be allergic to fast tempos in Mahler, then, this recording is not for you, but if that’s not a problem you’ll find this the greatest Mahler Eighth ever issued. I’ve hereby retired the Haitink recording from my collection; good as it is, it doesn’t have Kubelík’s overwhelming emotional impact. Since not every performance in the Kubelík set is of equal quality (no conductor’s integral set is consistently great), I encourage you to add this disc to your collection. Audite’s 24-bit remastering brings out every detail of this performance with stunning warmth and clarity. I’d compare the sound favorably to any all-digital Eighth on the market.

The Jewish Daily Forward

| July 28, 2010 | Benjamin Ivry | July 28, 2010

A Lively Musical Corpus

Gustav Mahler, Almost a Century Dead and Still Kicking

Although other composers are most suitably celebrated on the anniversariesMehr lesen

Audiophile Audition | July 2, 2010 | Patrick P.L. Lam | July 2, 2010 Rafael Kubelik and the Bavarian Radio Symphony Orchestra attest to this Mahlerian vision through a combination of technical command and musical coherency.

“I have just completed my 8th – it is the greatest I’ve ever done.Mehr lesen

Infodad.com | June 24, 2010 | June 24, 2010

With Mahler’s music now so popular – with a veritable flood ofMehr lesen

Infodad.com | 01.06.2010 | June 1, 2010

With Mahler’s music now so popular – with a veritable flood ofMehr lesen

Sunday Times | May 30, 2010 | Dan Cairns | May 30, 2010

The Czech conductor Rafael Kubelik’s years as director of the BavarianMehr lesen

The New York Sun | April 16, 2008 | Benjamin Ivry | April 16, 2008

In Stephen Sondheim's 1970 musical "Company," Elaine Stritch raspily sang aMehr lesen

Classica-Répertoire | novembre 2006 | Stéphane Friédérich | November 1, 2006

ecoute comparée – La Symphonie n°1 «Titan» de Gustav Mahler

Audition en aveugle

Rafael Kubelik et l'Orchestre symphonique de la Radio de Bavière (DG,Mehr lesen

www.allmusic.com | 01.12.2005 | Blair Sanderson | December 1, 2005

Rafael Kubelik made this live recording of Gustav Mahler's Symphony No. 8Mehr lesen

Classica-Répertoire | septembre 2005 | Stéphane Friédérich | September 1, 2005 La Sixième Symphonie de Gustav Mahler

Une soixante d’interprétations étaient en compétition pour cetteMehr lesen

www.SA-CD.net | August 26, 2005 | Mark Wagner | August 6, 2005

Hmmmmm.....<br /> <br /> First, I will say that I have never heard a recording orMehr lesen

First, I will say that I have never heard a recording or

www.ionarts.org | Friday, July 08, 2005 | July 8, 2005 Live Recordings of Mahler's Eighth

Speaking of such a performance, Rafael Kubelik's 8th on Audite was alsoMehr lesen

www.SA-CD.net | June 9, 2005 | Oscar Gil | June 9, 2005

Kubelik is one of the truly great Mahler conductors. He focuses on the moreMehr lesen

Le Monde de la Musique | Juin 2005 | Patrick Szersnovicz | June 1, 2005

Œuvre « officielle » chantant la joie de créer, vocale d'un bout à l'autre, la Huitième Symphonie « des Mille » (1906) est gagnée parMehr lesen

Si toute interprétation doit venir en aide à l'insuffisance des œuvres, la Huitième Symphonie requiert une interprétation parfaite. Enregistré « live » le 24 juin 1970 à Munich, à la tête d'un orchestre et de chanteurs exemplaires, Rafael Kubelik offre une vision puissante, « moderniste » et très proche de sa – magnifique – version officielle réalisée pour DG à la même époque. Si l'on demeure assez loin de l'exaltation d'un Bernstein ou de l'enthousiasme d'un Ozawa, l'équilibre et la rapidité des tempos, l'absence de pathos donnent la priorité au tissu musical. Le chef souligne dans le « Veni Creator » tout l'acquis des symphonies instrumentales précédentes et évite, dans la « Scène de Faust », l'écueil d'une simple succession d'airs et de chœurs. La prise de son, malgré l'excellence du report, n'est pas parfaite, mais la qualité des solistes vocaux est unique dans la discographie.

Classica-Répertoire | Juin 2005 | Stéphane Friédérich | June 1, 2005

Audite poursuit son intégrale live des symphonies de Mahler en nousMehr lesen

www.ClassicsToday.com | May 2005 | David Hurwitz | May 1, 2005

This live Mahler Symphony No. 8, made the same month as Rafael Kubelik'sMehr lesen

www.classicstodayfrance.com | Mai 2005 | Christophe Huss | May 1, 2005

Quel incroyable contraste avec la version Nagano qui paraît en mêmeMehr lesen

Diapason | Mai 2005 | Jean-Charles Hoffele | May 1, 2005

Ce n'est pas la relative méforme de Norma Procter qui fragilisera le geste épique de Kubelik dans ce concert inédit, enregistré en même temps queMehr lesen

La Seconde scène de Faust est ici un opéra : les chanteurs incarnent les personnages idéaux voulus par Goethe avec un sens dramatique que certains trouveront trop prononcé. Lorsqu'on entend la coda soulevée par Kubelik, galvanisée, on comprend que la 8e est une symphonie sans ombre, un chant du cosmos radieux avec l'être humain en son centre. Elle célèbre les noces de la vie et de l'univers avant que ne revienne le peuple de fantômes qui n'a presque jamais quitté le compositeur.

Muzyka21 | maj 2005 | Michał Szulakowski | May 1, 2005

„Wszystkie moje wcześniejsze symfonie były tylko preludium do tejMehr lesen

klassik.com | April 2005 | Miquel Cabruja | April 18, 2005 Mehrkanaligkeit

In immer kürzeren Abständen wirft die Musikindustrie neue Formate auf denMehr lesen

Pizzicato | 3/2005 | Rémy Franck | March 1, 2005

Am 25. & 26. Juni 1970 nahm Rafael Kubelik die Achte Mahler im Studio für die Deutsche Grammophon auf. Am 24 Juni entstand mit demselbenMehr lesen

klassik-heute.com | Februar 2005 | Sixtus König | February 8, 2005

Die Aufführung von Gustav Mahlers achter Sinfonie im Juni 1970 bildeteMehr lesen

Wiener Zeitung | Samstag, 05. Februar 2005 | Edwin Baumgartner | February 5, 2005 Kubelik: Mahler-Symphonien 6, 7 und 8

Rafael Kubelik war der Prototyp des hochintelligenten und dabeiMehr lesen

Wiener Zeitung | Samstag, 05. Februar 2005 | Edwin Baumgartner | February 5, 2005 Kubelik: Mahler-Symphonien 6, 7 und 8

Rafael Kubelik war der Prototyp des hochintelligenten und dabeiMehr lesen

www.new-classics.co.uk | January 2005 | January 1, 2005

In this outstanding live recording dating from 1970, Rafael Kubelik conducts the Bavarian Radio Symphony Orchestra in Mahler’s Das Lied von der ErdeMehr lesen

Lippische Landeszeitung | 05.02.2004 | fla | February 5, 2004

Historische Aufnahme ausgezeichnet

Label aus Hiddesen bekommt Cannes Classical Award

„Wir freuen uns sehr über diese Anerkennung“, heißt es bescheiden inMehr lesen

www.musicweb-international.com | February 2004 | Tony Duggan | February 1, 2004

Unlike the Audite release of Rafael Kubelik conducting Mahler’s First Symphony in 1971 already reviewed, this "live" recording of the Sixth datesMehr lesen

As I wrote when reviewing the Audite release of the First Symphony, Kubelik’s reputation in Mahler is often misleading. You often see expressions like "understated", "lightweight" and "lyrical" ascribed to it. It’s all relative, of course. True, Kubelik is certainly especially effective when Mahler goes outdoors, back to nature and the "Wunderhorn" moods. But he can also surprise us in those later works where a more astringent, Modernist, fractured approach is called for. This is especially the case if you are prepared to see those crucial aspects through the tinted glass of nature awareness and in context with how he sees the works that go before and after them. No better illustration of his ability to take in the advanced, forward-looking aspect of Mahler's work is provided by his approach to this most Modernist of Mahler’s symphonies.

Kubelik’s performance of the Sixth is astringent and very pro-active. This is the music of a man of action and vigour which, when Mahler wrote it, he certainly was. The first movement is very fast and this certainly stresses the classical basis of this most classically structured movement and therefore, I believe, the nature of the Tragedy embodied. It makes us see Mahler’s "hero" prior to the tragedy that overwhelms him in the last movement in that the pressing forward stresses optimism, a head held high, a corrective to those accounts that seem to want to condemn Mahler’s hero to his doom from the word go, like Barbirolli, for example. It also has the effect of making the music jagged and nervy in the way the episodes tumble past kaleidoscopically. I must praise the Bavarian Radio Orchestra here for managing to hang on so unerringly to the notes most of the time. Of course the DG studio version means that there are no errors of playing but you could argue that if you are going to hear a one-off "live" performance a few mistakes only add to the tension. Remember, however, that Kubelik’s tempi in Mahler are always on average faster than his colleagues and that ought to mitigate a little the speeds encountered here.

The Scherzo is placed second and reinforces the energy, rigour and astringency I remarked on in the first movement. As usual Kubelik is consistent and uncompromising to his vision. Perhaps the speed adopted here does fail to convey the peculiar "gait" of the music and that must be a minus. After this the third movement is beautifully free-flowing and unselfconscious. In fact it is hard to imagine a performance of this movement that could be much better in the way it seems to unfold unassisted, moving in one great breath to a glorious climax that is more effective for being neither under nor over -stated. Notice particularly the nostalgic solo trumpet that is as true a Mahlerian sound as you could wish for. The close-in recording also allows many details to emerge that you may not have hitherto heard so well.

The opening of the last movement is superbly done with trenchancy and harsh detail unflinchingly presented. The main allegro passages emit the same white-hot intensity of the first two movements and yet there remains a controlling mind behind it to guard against the intensity turning into abandonment and so the tension is ratcheted up. There are, as ever, no histrionics from Kubelik. Indeed there is from him just a tunnel-visioned concentration. However, I did begin to feel, particularly after the first hammer blow, that all of this high intensity actually threatens to overwhelm the music’s innate poetry where there needs to be a degree more flexibility, a degree more humanity. That this impression crucially impedes the listener’s ability to notice contrasting passages where you could reflect on what has gone and what might be to come. I suppose you could say that Kubelik allows no time to catch the breath and I really think there should be some. In fact I think much the same can be said about the first two movements under Kubelik but that it takes the experience of the fourth movement pitched at this pace to really bring this home. The Coda, where the trombone section intones a funeral oration over the remains of the fallen hero is, however, under Kubelik an extraordinary sound with a degree of vibrato allowed to the players that chills to the marrow. That, at least, is deeply moving and well worth waiting for even if my overall verdict on Kubelik in this whole symphony is that it falls short of the greatest.

In the end I am left with the feeling that this is a partial picture of the Sixth, albeit an impressive one, but still a partial one which leaves us unsatisfied. I would advise you to turn to Thomas Sanderling on RS which I deal with in my Mahler recordings survey or Gunther Herbig whose recording on Berlin Classics I nominated a Record of the Month, there is also Mariss Jansons on LSO Live whose recent recording impressed me greatly and Michael Gielen on Hänssler. Look to all of those those first.

Rafael Kubelik views the Sixth as high intensity drama right the way through. A perfectly valid view and thrillingly delivered. But this protean work succeeds when its protean nature is laid out before us and Kubelik, eyes wide open, does not really do that. More space, more weight, more room is needed throughout and at particularly crucial nodal points (the two hammer-blows are too lightweight in preparation and delivery, for example) to really move and impress as this symphony can under those mentioned above.

Kubelik’s Mahler Sixth is a very vivid, though very partial, view of the work.

www.musicweb-international.com | 1/2004 | Tony Duggan | January 1, 2004

For many Mahlerites over a certain age Rafael Kubelik has always been there, like a dependable uncle, part of the Mahler family landscape for as longMehr lesen

Yet it has never quite made the "splash" those by some of his colleagues have done. Kubelik’s view of Mahler is not one that attaches itself to the mind at a first, or even a second, listening. Kubelik was never the man for quick fixes or cheap thrills in any music he conducted. So in Mahler not for him the heart-on-sleeve of a Bernstein, the machine-like precision of a Solti, or the dark 19th century psychology of a Tennstedt. Kubelik’s Mahler goes back to folk roots, pursues more refined textures, accentuates song, winkles out a lyrical aspect and so has the reputation of playing down the angst, the passion, the grandeur. But note that I was careful to use the word "reputation". I often wonder whether those who tend to pass over Kubelik’s Mahler as honourable failure have actually listened hard over a period of time to those recordings. I think if they had they would, in the end, come to agree that whilst Kubelik is certainly excellent at those qualities for which his Mahler is always recognised he is also just as capable of delivering the full "Mahler Monty" as everyone else is. It’s just that he anchors it harder in those very aspects he is praised for, giving the rest a unique canvas on which he can let whole of the music breathe and expand. It’s all a question of perspective. Kubelik’s Mahler takes time, always remember that.

In his studio cycle the First Symphony has always been one of the most enduring. It has appeared over and over again among the top recommendations of many critics, including this one. Many others who tend not to rate Kubelik highly in certain later Mahler Symphonies if they were of a mind to rate his First Symphony might feel constrained to point out that the First is, after all, a "Wunderhorn" symphony and that it is in the "Wunderhorn" mood Kubelik was at his strongest. I don’t disagree with that as an explanation but, as I have said, I think that in Mahler Rafael Kubelik was so much more than a two or three trick pony. In fact in the First Symphony Kubelik’s ability to bring out the grotesques, the heaven stormings and the romance was just as strong as Bernstein or Solti. It’s a case of perspectives again.

The studio First Symphony did have one particular drawback noted by even its most fervent admirers. A drawback it shared with most of the other recordings in the cycle too. It lay in the recorded sound given to the Bavarian Radio Orchestra by the DG engineers in Munich. Balances were close, almost brittle. The brass, trumpets especially, were shrill and raucous. There was an overall "boxy" feeling to the sound picture. I have never been one to dismiss a recording on the basis of recorded sound alone unless literally un-listenable. However, even I regretted the sound that this superb performance had been given. This is not the only reason I am going to recommend this 1979 "live" recording on Audite of the First over the older DG, but it is an important one. At last we can now hear Kubelik’s magnificent interpretation of this symphony, and the response of his excellent orchestra, in beautifully balanced and realistic sound about which I can have no criticism and nothing but praise.

Twelve years after the studio recording Kubelik seems to have taken his interpretation of the work a stage further. Whether it’s a case of "live" performance before an audience leading him to take a few more risks, play a little more to the gallery, or whether it’s simply the fact that he has thought more and more about the work in subsequent performances, I don’t know. What I do know is that every aspect of his interpretation I admired first time around is presented with a degree more certainty, as though the 1967 version was "work in progress" and this is the final statement. (Which, in fact, it was when you consider Kubelik first recorded the work for Decca in Vienna in the 1950s.)

Straight away the opening benefits from the spacious recording with the mellow horns and distant trumpets really giving that sense of otherworldliness that Mahler was surely aiming for. Notice also the woodwinds’ better balancing in the exposition main theme which Kubelik unfolds with a telling degree more lyricism. One interesting point to emerge is that after twelve years Kubelik has decided to dispense with the exposition repeat and it doesn’t appear to be needed. In the development the string slides are done to perfection, as good as Horenstein’s in his old Vox recording. Kubelik also manages an admirable sense of mounting malevolence when the bass drum starts to tap softly. Nature is frightening, Mahler is telling us, and Kubelik agrees. The recapitulation builds inexorably and the coda arrives with great sweep and power. At the end the feeling is that Kubelik has imagined the whole movement in one breath.

The second movement has a well-nigh perfect balance of forward momentum and weight. There is trenchancy here, but there is also a dance element that is so essential to make the music work. Some conductors seem to regard the Trio as a perfunctory interlude, but not Kubelik. He lavishes the same care on this that he lavishes on everything else and the pressing forward he was careful to observe in the main scherzo means he doesn’t need to relax too much in order to give the right sense of respite. There is also an air of the ironic, a feeling we are being given the other side of one coin.

The third movement is one of the most extraordinary pieces of music Mahler ever wrote. The fact that it was amongst his earliest compositions makes it even more astounding. I have always believed that in this movement Mahler announces himself a a truly unique voice for the first time and Kubelik certainly seems to think this in the way he rises to the occasion. He has always appreciated the wonderful colours and sounds that must have so shocked the first audience but in this recording we are, once more, a stage further on in the interpretation than in his previous version. Right at the start he has a double bass soloist prepared to sound truly sinister, more so than in 1971, and one who you can really hear properly also. As the funeral march develops a real sense of middle European horror is laid out before us. All the more sinister for being understated by Mahler but delivered perfectly by a conductor who is prepared to ask his players to sound cheap, to colour the darker tones. This aspect is especially evident in the band interruptions where the bass drum and cymbals have a slightly off-colour Teutonic edge which, when they return after the limpid central section, are even more insinuating and menacing. Kubelik seems to have such confidence in the music that he is able to bring off an effect like this where others don’t. In all it’s a remarkably potent mix that Kubelik and his players deliver in this movement though he never overplays, always anchors in the music’s roots.

In the chaos unleashed at the start of the last movement you can now, once more, hear everything in proper perspective, the brass especially. The ensuing big tune is delivered with all the experience Kubelik has accumulated by this time, but even I caught my breath at how he holds back a little at the restatement. Even though the lovely passage of nostalgic recall just prior to the towering coda expresses a depth and profundity only hinted at in 1967 it is the coda itself which will stay in your mind. As with the studio recording Kubelik is anxious for you to hear what the strings are doing whilst the main power is carried by brass and percussion. Kubelik is also too experienced a Mahlerian to rush the ending. Too many conductors press down on the accelerator here, as if this will make the music more exciting, and how wrong they are to try. Listen to how Kubelik holds on to the tempo just enough to allow every note to tell. He knows this is so much more than just a virtuoso display, that it is a statement of Mahler’s own arrival, and his care and regard for this work from start to finish stays with him to the final note.

This is a top recommendation for this symphony. It supersedes Kubelik’s own studio recording on DG and, I think, surpasses in achievement those by Horenstein (Vox CDX2 5508) and Barbirolli (Dutton CDSJB 1015) to name two other favourite versions I regard as essential to any collection but which must now be thought of as alternatives to this Audite release.

Simply indispensable.

Zeitpunkt Studentenführer | 1/2004 | Beate Hiltner-Hennenberg | January 1, 2004

„Wie mit einem Schlag sind alle Schleusen in mir geöffnet!“ –Mehr lesen

Scherzo | Num. 181, Diciembre 2003 | Enrique Pérez Adrián | December 1, 2003

Una versión elocuente, fervorosa y emotiva, otro de los grandes aciertos mahlerianos de este sensacional director

Rafael Kubelik - A la altura de las mejores

Otra entrega más del Mahler en vivo de Kubelik. Esta vez se trata de laMehr lesen

Badische Zeitung | 18.11.2003 | Heinz W. Koch | November 18, 2003

... Wie spezifisch, ja wie radikal sich Gielens Mahler ausnimmt, erhellt schlagartig, wenn man Rafael Kubeliks dreieinhalb Jahrzehnte alte und vorMehr lesen

Eine gehörige Überraschung gab’s schon einmal – als nämlich die nie veröffentlichten Münchner Funk-„Meistersinger“ von 1967 plötzlich zu haben waren. Jetzt ist es Gustav Mahlers drei Jahre später eingespieltes „Lied von der Erde“, das erstmals über die Ladentische geht. Es gehört zu einer Mahler Gesamtaufnahme, die offenbar vor der rühmlich bekannten bei der Deutschen Grammophon entstand. Zumindest bei den hier behandelten Sinfonien Nr. 3 und Nr. 6 war das der Fall. Beim „Lied von der Erde“ offeriert das Symphonie-Orchester des Bayerischen Rundfunks, dessen Chef Kubelik damals war, ein erstaunlich präsentes, erstaunlich aufgesplittertes Klangbild, das sowohl das Idyllisch-Graziöse hervorkehrt wie das Schwerblütig-Ausdrucksgesättigte mit großem liedsinfonischem Atem erfüllt – eine erstrangige Wiedergabe.

Auch die beiden 1967/68 erarbeiteten Sinfonien erweisen sich als bestechend durchhörbar. Vielleicht geht Kubelik eine Spur naiver vor als die beim Sezieren der Partitur schärfer verfahrenden Dirigenten wie Gielen, bricht sich, wo es geht, das ererbte böhmische Musikantentum zumindest für Momente Bahn. Da staunt einer eher vor Mahler, als dass er ihn zu zerlegen sucht. Wenn es eine Verwandtschaft gibt, dann ist es die zu Bernstein. Das Triumphale der „Dritten“, das Nostalgische an ihr wird nicht als Artefakt betrachtet, sondern „wie es ist“: Emotion zur Analyse. ...

(aus einer Besprechung mit den Mahler-Interpretationen Michael Gielens)

Badische Zeitung | 18.11.2003 | Heinz W. Koch | November 18, 2003

... Wie spezifisch, ja wie radikal sich Gielens Mahler ausnimmt, erhellt schlagartig, wenn man Rafael Kubeliks dreieinhalb Jahrzehnte alte und vorMehr lesen

Eine gehörige Überraschung gab’s schon einmal – als nämlich die nie veröffentlichten Münchner Funk-„Meistersinger“ von 1967 plötzlich zu haben waren. Jetzt ist es Gustav Mahlers drei Jahre später eingespieltes „Lied von der Erde“, das erstmals über die Ladentische geht. Es gehört zu einer Mahler Gesamtaufnahme, die offenbar vor der rühmlich bekannten bei der Deutschen Grammophon entstand. Zumindest bei den hier behandelten Sinfonien Nr. 3 und Nr. 6 war das der Fall. Beim „Lied von der Erde“ offeriert das Symphonie-Orchester des Bayerischen Rundfunks, dessen Chef Kubelik damals war, ein erstaunlich präsentes, erstaunlich aufgesplittertes Klangbild, das sowohl das Idyllisch-Graziöse hervorkehrt wie das Schwerblütig-Ausdrucksgesättigte mit großem liedsinfonischem Atem erfüllt – eine erstrangige Wiedergabe.

Auch die beiden 1967/68 erarbeiteten Sinfonien erweisen sich als bestechend durchhörbar. Vielleicht geht Kubelik eine Spur naiver vor als die beim Sezieren der Partitur schärfer verfahrenden Dirigenten wie Gielen, bricht sich, wo es geht, das ererbte böhmische Musikantentum zumindest für Momente Bahn. Da staunt einer eher vor Mahler, als dass er ihn zu zerlegen sucht. Wenn es eine Verwandtschaft gibt, dann ist es die zu Bernstein. Das Triumphale der „Dritten“, das Nostalgische an ihr wird nicht als Artefakt betrachtet, sondern „wie es ist“: Emotion zur Analyse. ...

(aus einer Besprechung mit den Mahler-Interpretationen Michael Gielens)

CD Compact | n°169 (octobre 2003) | Benjamín Fontvelia | October 1, 2003 Rafael Kubelik/Audite

Sin la aparatosa presencia mediática de Karajan y Bernstein, en su rincónMehr lesen

Gramophone | October 2003 | Rob Cowan | October 1, 2003 Kubelik takes the Stage

Some years ago I was involved in a discussion concerning Wilhelm Furtwängler's potential artistic heir. Who might he be? There was no lack ofMehr lesen

For example, compare Kubelik's 1975 DG studio recording of Beethoven's Fourth Symphony with the Israel Philharmonic with the live Bavarian RSO Audite version of four years later. The IPO account is taut and incisive, with an explosive fortissimo just before the coda (at 5'52", i.e. bar 312) that sounds as if it has been aided from the control desk. Turn then to the BRSO version, the lead-up at around 4'25" to that same passage (here sounding wholly natural), so much more gripping, where second fiddles, violas and cellos thrust their responses to tremolando first fiddles. The energy level is still laudably high but the sense of intense engagement is almost palpable. Again, with the Boston recording of the Fifth, handsome and well played as it undoubtedly is (and with the finale's repeat intact, which isn't the case on Audite), there is little comparison with the freer, airier and more responsive live relay. I'm thinking especially the slow movement, so humble and expressive, almost hymn-like in places – for example, the Bachian string counterpoint from 4'27''. Also, the Boston recording places first and second violins on the left: the Audite option has them divided, as per Kubelik’s preferred norm.

Audite’s Tchaikovsky coupling is an out-and-out winner. Kubelik made two studio recordings of the Fourth Symphony (with the Chicago SO and Vienna PO), both set around a lyrical axis, but this live version has a unique emotive impetuosity, especially in the development section of the first movement. The Andantino relates a burning nostalgia without exaggeration, whereas the scherzo – taken at a real lick – becomes a quiet choir of balalaikas. The April 1969 performance of the Violin Concerto was also Pinchas Zukerman's German début and aside from Kubelik's facilitating responsiveness, there's the warmth and immediacy of the youthful Zukerman's tone and the precision of his bowing. Both performances confirm Kubelik as among the most sympathetic of Tchaikovsky conductors, a genuine listener who relates what he hears, not what he wants to confess through the music.

Much the same might be said of Kubelik's Mahler, whether for DG or the various live alternatives currently appearing on Audite. In the case of ‘Das Lied von der Erde’ there is no DG predecessor, but even if there was, I doubt that it would surpass the live relay of February 1970 with Waldemar Kmentt and Dame Janet Baker, so dashing, pliant and deeply felt, whether in the subtly traced clarinet counterpoint near the start of ‘Von der Jugend’ or the way Baker re-emerges after the funereal processional in ‘Der Abschied’, as if altered forever by a profound visitation.

Scherzo | N° 178, Septiembre 2003 | Enrique Pérez Adrián | September 1, 2003

Una gran versión que sin duda hará mella espiritual en cualquier oyente sensible que se acerque a ella

Mathis, Brendel, Kmentt, Baker y Kubelik - Dos nuevas dianas

Audite nos trae dos nuevos conciertos de Rafael Kubelik de los años 70, deMehr lesen

El País

| 19.04.2003 | Javier Pérez Senz | April 19, 2003

Kubelik, en el corazón de Mahler

Dos sinfonías de Gustav Mahler grabadas en vivo abren la edición que el sello Audite dedica al director checo Rafael Kubelik, uno de los grandes mahlerianos de la historia.

[...] dirige el célebre adagietto con un encendido lirismo y una intensidad que hipnotiza al oyente –, situándose entre las mejores de la discografía.Mehr lesen

El País

| 19.04.2003 | Javier Pérez Senz | April 19, 2003

Kubelik, en el corazón de Mahler

Dos sinfonías de Gustav Mahler grabadas en vivo abren la edición que el sello Audite dedica al director checo Rafael Kubelik, uno de los grandes mahlerianos de la historia.

[...] dirige el célebre adagietto con un encendido lirismo y una intensidad que hipnotiza al oyente –, situándose entre las mejores de la discografía.Mehr lesen

El País

| 19.04.2003 | Javier Pérez Senz | April 19, 2003

Kubelik, en el corazón de Mahler

Dos sinfonías de Gustav Mahler grabadas en vivo abren la edición que el sello Audite dedica al director checo Rafael Kubelik, uno de los grandes mahlerianos de la historia.

[...] dirige el célebre adagietto con un encendido lirismo y una intensidad que hipnotiza al oyente –, situándose entre las mejores de la discografía.Mehr lesen

El País

| 19.04.2003 | Javier Pérez Senz | April 19, 2003

Kubelik, en el corazón de Mahler

Dos sinfonías de Gustav Mahler grabadas en vivo abren la edición que el sello Audite dedica al director checo Rafael Kubelik, uno de los grandes mahlerianos de la historia.

[...] dirige el célebre adagietto con un encendido lirismo y una intensidad que hipnotiza al oyente –, situándose entre las mejores de la discografía.Mehr lesen

Flensborg Avis | 09.04.2003 | Lars Geerdes | April 9, 2003

Skelsættende tysk Mahlerindspilning genudgivet

Live-optagelse fra 1970 kan nu købes på cd

Da dirigenten Rafael Kubelik (1914-1996) i 1961 tiltrådte stillingen somMehr lesen

www.musicweb-international.com | 01.04.2003 | Tony Duggan | April 1, 2003

Here is one of the great "lost" Mahler recordings now properly restored. When Rafael Kubelik made his outstanding studio Mahler cycle in Munich for DGMehr lesen

For me Janet Baker has always been the greatest interpreter of the female/baritone songs in this work. Her Philips recording with Haitink on Eloquence (468 182-2) was long awaited even when it appeared and did not disappoint her admirers. In my survey of recordings of this work I believe I paid that version the attention it deserved singling out Baker for special praise. However even then I felt her interpretation on a BBC Radio Classics release taken from a later "live" performance in Manchester and conducted by Raymond Leppard was even better – deeper, more profound. The problem was that in no way could the BBC Northern Symphony Orchestra compare with the Concertgebouw, or her conductor Raymond Leppard compare with Bernard Haitink even though hearing Baker "live" seemed to add something to her interpretation. This was partly why when I heard the "pirate" of this Munich version I hoped for an official release. This too is "live" with all the benefit that brings but this time we have in Kubelik a Mahlerian of equal stature to Haitink and in the Bavarian Radio an orchestra that comes close to the Concertgebouw in depth of response to Mahler’s sound world. Matched with Waldemar Kmentt she also appears with a tenor who is, for me, superior to James King on the Haitink version and John Mitchinson on the Leppard, fine though both are.

The key to the greatness of Janet Baker in this work is her total identification with the words. Her care for every detail of them means she lives the part where some merely describe it. Her view of the music seems from the inside out. In these movements one thinks of Baker, Ludwig and Fassbaender among the women and Fischer-Dieskau among the men. In the second song you are made to feel what it is to be lonely rather than simply have loneliness described to you. Technically too she is on top form as the wild horses passage in "Von der Schönheit" proves. At no point in this crazy music does Baker ever give the impression that she will come to grief, even though the tempo adopted by her and Kubelik is suitably swift. They had one shot at this in front of an audience and it comes off triumphantly. Listen also to the delicacy of the description of the young girls swimming in the same movement. Finally in the "Abschied" her range, emotional and musical is total. Everything is covered here from the passages of sterile enunciation to the overwhelming emotional grandeur of the climaxes and all points between subtly graded. Overall this is one of those interpretations that contain depths that will take years to plumb.

Of all the great recordings of this work I know there has, for me, so far only been one where I feel that two of the greatest interpreters are matched on the same recording. These are Christa Ludwig and Fritz Wunderlich for Klemperer on EMI. But now with this release I think there is a second since Waldemar Kmentt is just as convincing in his songs as Janet Baker is in hers. In fact I believe Kmentt can be compared with Wunderlich, Peter Schreier and Julius Patzak as the finest interpreters in the tenor songs on record. In "Das Trinklied" Kmentt is towering, challenging the music to break him in the dramatic sections, but emerging unscathed from them. The "Dark is life, is death" refrain has a world-weary depth that few save Schreier and Wunderlich can match and the "ape on the grave" climax is fearless in his nightmarish delivery. Like Baker, Kmentt can also walk the delicate passages of this work with equal effect. His description of the arrival of spring in "Der Trunkene im Fruhling" is magical and his word painting in "Von Der Jugend" piquant and sharp.

Kubelik’s greatness as a Mahler conductor was his ability to cover the whole range of the music from uncomplicated nature painting to calculated high drama and seem equally at home everywhere. He attends to all details of this music with care and discretion, always taking care of the bigger picture too, balancing it with the inner detail. Notice the woodwinds during the funeral march in "Der Abscheid" where every strand is clearly delineated, or the effect of getting his mandolin to play tremolo in the same movement marking up the chinoiserie in a most evocative and unique way. He also recognises what I have always believed to be a crucial aspect of this work. That the two soloists are the equal partners with the conductor and that he is there to support them. With great soloists like these, that is easier. But countless examples of his support for his soloists are apparent in this performance along with the preparation of his orchestra to act almost as a third soloist. The purely instrumental passages in "Der Abschied" reveal Mahler conducting of the highest order. Listen to the birds passage and also to the deep bass growls before the funeral march.

The sound recording leaves little to be desired. It is hard to tell it was made over thirty years ago for radio broadcast. I like the balances between woodwind and strings and the warmth of the acoustic around the orchestra and soloists in the chamber-like sections. The balance between soloists and orchestra are exemplary also. Even the distinctive acoustic of the Herkulessaal is made to sound perfectly suited to the music. You can hear everything and with solo players in the orchestra as eloquent as the two singers are this is important and adds another plus to this disc. In sound terms this more than matches the best versions of this work and musically it is the equal of Klemperer on EMI (5 66892 2), Sanderling on Berlin Classics (0094022BC) and Horenstein on BBC Legends (BBCL 4042-2). All very different though each one of those comparable versions are in their interpretative approach. Indeed, this Kubelik recording has the effect of taking many of the virtues of all those great recordings and stitching them into a new and deeply satisfying whole.

This is one of the all-time great Mahler recordings: a classic version of this inexhaustible masterpiece in every way. Indeed I think there are none to surpass it, perhaps only to equal it. You will be moved, delighted and changed by it. I cannot recommend it too highly as it goes to the top of my list for this work.

Nordsee-Zeitung | Nr. 57/2003 | Sebastian Loskant | March 8, 2003

Es war ein Tscheche, der den Münchenern den Spätromantiker Gustav MahlerMehr lesen

Das Orchester | 3/2003 | Johannes Killyen | March 1, 2003

Um eines von Gustav Mahlers großen Werken neu auf dem übersättigtenMehr lesen

Die Rheinpfalz | 12.02.2003 | Gerhard Tetzlaf | February 12, 2003 Idealer Interpret – Livemitschnitte unter Rafael Kubelik

Die Gesamtaufnahme der Sinfonien Gustav Mahlers durch Rafael Kubelik undMehr lesen

Die Rheinpfalz | 12.02.2003 | Gerhard Tetzlaf | February 12, 2003 Idealer Interpret – Livemitschnitte unter Rafael Kubelik

Die Gesamtaufnahme der Sinfonien Gustav Mahlers durch Rafael Kubelik undMehr lesen

Stereoplay | 1/2003 | Ulrich Schreiber | January 1, 2003

Marktpolitisch mag der Audite-Versuch, dem von der DG im Studio fixiertenMehr lesen

klassik.com | 19.12.2002 | Erik Daumann | December 19, 2002 | source: http://magazin.k... Von Böhme zu Böhme

Das Label ‚audite’ des Diplom-Tonmeisters Ludger Böckenhoff ausMehr lesen

WDR 3 | 03.12.2002 | Michael Schwalb | December 3, 2002

Hörproben-Neue CDs, am Mikrophon Michael Schwalb. Mitgebracht habe ichMehr lesen

klassik-heute.com | 02.12.2002 | Mario Gerteis | December 2, 2002

In der ersten Mahler-Welle auf (Stereo-)Schallplatten spielte derMehr lesen

Fono Forum | 11/02 | Christian Wildhagen | November 1, 2002 Glücksgriff

Dieser Live-Mitschnitt stellt eine echte Erweiterung der Kubelik-Diskographie dar, denn "Das Lied von der Erde" fehlt in seinem Studio-Mahler-Zyklus.Mehr lesen

Rondo | 17.10.202 | Matthias Kornemann | October 17, 2002

Viele Dirigenten hat es am Jahrhundertende angezogen, dieses "Lied von derMehr lesen

Classic Record Collector | 10/2002 | Christopher Breunig | October 1, 2002

The German firm Audite has given us not only this near complete live cycle of Mahler symphonies (sans 4 or 8), but valuable Kubelik/Curzon readings ofMehr lesen

Recorded between 1967 and 1971, Kubelik’s DG cycle has been at budget price for some time now and the Audite alternatives of 1, 5 and 7 have been in the shops for months. The NHK-recorded Ninth, made during a 1975 Tokyo visit by the Bavarian RSO, was reviewed in CRC, Spring 2001 (I found the sound unfocused and the brass pinched in sound, but welcomed in particular playing ‘ablaze’ after the visionary episode in the Rondo burleske and a crowning final). No. 1 in DG is widely admired but this 1979 version is more poetic still, wonderfully so in the introduction and trio at (II). There is something of a pall of resonance in place of applause, cut from all these Audite transfers. In No. 7 the balance is more airy than DG’s multi-miked productions, and (as in No. 5) Kubelik sounds less constrained than when working under studio conditions, although rhythm in the opening bars of (II) goes awry and the very opening note is succeeded by a sneeze! The disturbing and more shadowy extremes are more vividly characterized, the finale a riotous display.

Some critics feel that Kubelik gives us ‘Mahler-lite’, which may seem in comparison with, say, Chailly’s Decca cycle or the recent BPO/Abbado Third on DG – not to mention Bernstein’s. But there is plenty of energy here, and the divided strings with basses set to the rear left give openness to textures. However, the strings are not opulent and the trumpets are often piercing. It would be fair to say that Kubelik conducted Mahler as if it were Mozart!

As it happens, in the most controversial of his readings, No. 6, the DG is preferable to the Audite, where Kubelik projects little empathy with its slow movement and where the Scherzo is less cohesive. The real problem is that the very fast speed for (I) affects ail subsequent tempo relationships. Nor does the finale on No. 3, one of the glories of the DG cycle, quite have the same radiance; the singers are the same, the Tölz Boys making a sound one imagines Mahler must have heard in his head, and this performance predates the DG by one month. Nevertheless, these newer issues of Nos 2 and 3 are worth hearing, the ‘Resurrection’ not least for Brigitte Fassbaender’s account of ‘Urlicht’.

Nowadays every orchestra visiting London seems to programme Mahler’s Fifth Symphony as a showpiece, but in 1951 (when Bruno Walter’s 78rpm set was the collector’s only choice) a performance would surely have been uncommon even at the Concertgebouw – Mengelberg was prohibited from conducting in Holland from 1946 until he died that year. Although the start of (V) is marred by horns, this is an interesting, well executed account with a weightier sound, from what one can surmise through the inevitable dimness – the last note of (I) is almost inaudible. The three versions vary sufficiently to quote true timings (none is given by Tahra): (I) 11m 34s/12m 39s/11m 35s (Tahra/Audite/DG); (II) 13m/14m 52s/13m 52s; (III) 15m 56s/17m 54s/17m 23s; (IV) 9m 24s/10m 24s/9mm 44s); (V) 14m 26s/14m 57s/15m 29s. The live Munich version is tidier than on DG; the spectral imagery in (III) is heavier in effect, too; and in the Adagietto the dynamic and phrasing shadings and poetic quality of the string playing also give the live performance the edge. Towards the end of the finale, and elsewhere, the engineers reduced dynamic levels.

Tahra’s booklet comprises an untidily set-out synopsis of Kubelik’s career. Audite’s have full descriptions of the works with text for Nos 2 and 3, and different back-cover colour portraits of the conductor.

International Record Review | 10/2002 | Christopher Breuning | October 1, 2002

The German firm Audite has given us not only this near complete live cycle of Mahler symphonies (sans 4 or 8), but valuable Kubelik/Curzon readings ofMehr lesen

Recorded between 1967 and 1971, Kubelik’s DG cycle has been at budget price for some time now and the Audite alternatives of 1, 5 and 7 have been in the shops for months. The NHK-recorded Ninth, made during a 1975 Tokyo visit by the Bavarian RSO, was reviewed in CRC, Spring 2001 (I found the sound unfocused and the brass pinched in sound, but welcomed in particular playing ‘ablaze’ after the visionary episode in the Rondo burleske and a crowning final). No. 1 in DG is widely admired but this 1979 version is more poetic still, wonderfully so in the introduction and trio at (II). There is something of a pall of resonance in place of applause, cut from all these Audite transfers. In No. 7 the balance is more airy than DG’s multi-miked productions, and (as in No. 5) Kubelik sounds less constrained than when working under studio conditions, although rhythm in the opening bars of (II) goes awry and the very opening note is succeeded by a sneeze! The disturbing and more shadowy extremes are more vividly characterized, the finale a riotous display.

Some critics feel that Kubelik gives us ‘Mahler-lite’, which may seem in comparison with, say, Chailly’s Decca cycle or the recent BPO/Abbado Third on DG – not to mention Bernstein’s. But there is plenty of energy here, and the divided strings with basses set to the rear left give openness to textures. However, the strings are not opulent and the trumpets are often piercing. It would be fair to say that Kubelik conducted Mahler as if it were Mozart!

As it happens, in the most controversial of his readings, No. 6, the DG is preferable to the Audite, where Kubelik projects little empathy with its slow movement and where the Scherzo is less cohesive. The real problem is that the very fast speed for (I) affects ail subsequent tempo relationships. Nor does the finale on No. 3, one of the glories of the DG cycle, quite have the same radiance; the singers are the same, the Tölz Boys making a sound one imagines Mahler must have heard in his head, and this performance predates the DG by one month. Nevertheless, these newer issues of Nos 2 and 3 are worth hearing, the ‘Resurrection’ not least for Brigitte Fassbaender’s account of ‘Urlicht’.

Nowadays every orchestra visiting London seems to programme Mahler’s Fifth Symphony as a showpiece, but in 1951 (when Bruno Walter’s 78rpm set was the collector’s only choice) a performance would surely have been uncommon even at the Concertgebouw – Mengelberg was prohibited from conducting in Holland from 1946 until he died that year. Although the start of (V) is marred by horns, this is an interesting, well executed account with a weightier sound, from what one can surmise through the inevitable dimness – the last note of (I) is almost inaudible. The three versions vary sufficiently to quote true timings (none is given by Tahra): (I) 11m 34s/12m 39s/11m 35s (Tahra/Audite/DG); (II) 13m/14m 52s/13m 52s; (III) 15m 56s/17m 54s/17m 23s; (IV) 9m 24s/10m 24s/9mm 44s); (V) 14m 26s/14m 57s/15m 29s. The live Munich version is tidier than on DG; the spectral imagery in (III) is heavier in effect, too; and in the Adagietto the dynamic and phrasing shadings and poetic quality of the string playing also give the live performance the edge. Towards the end of the finale, and elsewhere, the engineers reduced dynamic levels.

Tahra’s booklet comprises an untidily set-out synopsis of Kubelik’s career. Audite’s have full descriptions of the works with text for Nos 2 and 3, and different back-cover colour portraits of the conductor.

International Record Review | 10/2002 | Christopher Breuning | October 1, 2002

The German firm Audite has given us not only this near complete live cycle of Mahler symphonies (sans 4 or 8), but valuable Kubelik/Curzon readings ofMehr lesen

Recorded between 1967 and 1971, Kubelik's DG cycle has been at budget price for some time now (Collector 463 738-2, ten discs) and the Audite alternatives of 1, 5 and 7 have been in the shops for months. The NHK-recorded Ninth (Audite 95471), made during a 1975 Tokyo visit by the Bavarian RSO, was reviewed in CRC, Spring 2001 (I found the sound unfocused and the brass pinched in sound, but welcomed in particular playing ‘ablaze’ after the visionary episode in the Rondo burleske and a crowning finale). No. 1 on DG is widely admired but this 1979 version is more poetic still, wonderfully so in the introduction and trio at (II). There is something of a pal of resonance in place of applause, cut from all these Audite transfers. In No.7 the balance is more airy than DG’s multi-miked productions, and (as in No.5) Kubelik sounds less constrained than when working under studio conditions, although rhythm in the opening bars of (II) goes awry and the very opening note is succeeded by a sneeze! The disturbing and more shadowy extremes are more vividly characterised, the finale a riotous display.

Some critics feet that Kubelik gives us ‘Mahler-lite’ which may seem so in comparison with, say, Chailly's Decca cycle or the recent BPO/Abbado Third on DG – not to mention Bernstein's. But there is plenty of energy here, and the divided strings with basses set to the rear left give openness to textures. However, the strings are not opulent and the trumpets are often piercing. It would be fair to say that Kubelik conducted Mahler as if it were Mozart!

As it happens, in the most controversial of his readings, No. 6, the DG is preferable to the Audite, where Kubelik projects little empathy with its slow movement and where the Scherzo is less cohesive. The real problem is that the very fast speed for (I) affects ail subsequent tempo relationships. Nor does the finale of No. 3. one of the glories of the DG cycle, quite have that same radiance; the singers are the same, the Tölz Boys making a sound one imagines Mahler must have beard in his head, and this performance predates the DG by one month. Nevertheless, these newer issues of Nos 2 and 3 are worth hearing, the ‘Resurrection’ not least for Brigitte Fassbaender's account of the ‘Urlicht’.

Nowadays, every orchestra visiting London seems to programme Mahler's Fifth Symphony as a Showpiece, but in 1951 (when Bruno Walter's 78rpm set was the collector's only choice) a performance would surely have been uncommon even at the Concertgebouw – Mengelberg was prohibited from conducting in Holland from 1946 until he died that year. Although the start of (V) is marred by the horns, this is an interesting, well executed account with a weightier sound, from what one can surmise through the inevitable dimness – the last note of (I) is almost inaudible. The three versions vary sufficiently to quote true timings (none is given by Tahra): (I) 11m 34s/12m 39s/11m 35s (Tahra/Audite/DG); (II) 13m/14m 52s/13m 52s; (III) 15m 56s/17m 54s/17m 23s; (IV) 9m 24s/10m 24s/9m 44s); (V) 14m 26s/14m 57s/15m 29s. The live Munich version is tidier than on DG; the spectral imagery in (III) is

heavier in effect, too; and in the Adagietto the dynamic and phrasing shadings and poetic quality of the string playing also give the live performance the edge. Towards the end of the finale, and elsewhere the engineers reduced dynamic levels.

Tahra's booklet comprises an untidily set-out synopsis of Kubelik's career. Audite's have full description of the works with texts for Nos 2 and 3, and different back-cover colour portraits of the conductor.

www.amazon.de | 1. Oktober 2002 | October 1, 2002 | source: https://www.amaz... Fernöstliche Musik ganz nah!

Rafael Kubelik beschreitet sicher den Grat zwischen romantisch üppigem Klang und klassischer Genauigkeit, lässt die Musik weit schwingen, dasMehr lesen

International Record Review | 10/2002 | Christopher Breuning | October 1, 2002

The German firm Audite has given us not only this near complete live cycle of Mahler symphonies (sans 4 or 8), but valuable Kubelik/Curzon readings ofMehr lesen

Recorded between 1967 and 1971, Kubelik’s DG cycle has been at budget price for some time now and the Audite alternatives of 1, 5 and 7 have been in the shops for months. The NHK-recorded Ninth, made during a 1975 Tokyo visit by the Bavarian RSO, was reviewed in CRC, Spring 2001 (I found the sound unfocused and the brass pinched in sound, but welcomed in particular playing ‘ablaze’ after the visionary episode in the Rondo burleske and a crowning final). No. 1 in DG is widely admired but this 1979 version is more poetic still, wonderfully so in the introduction and trio at (II). There is something of a pall of resonance in place of applause, cut from all these Audite transfers. In No. 7 the balance is more airy than DG’s multi-miked productions, and (as in No. 5) Kubelik sounds less constrained than when working under studio conditions, although rhythm in the opening bars of (II) goes awry and the very opening note is succeeded by a sneeze! The disturbing and more shadowy extremes are more vividly characterized, the finale a riotous display.

Some critics feel that Kubelik gives us ‘Mahler-lite’, which may seem in comparison with, say, Chailly’s Decca cycle or the recent BPO/Abbado Third on DG – not to mention Bernstein’s. But there is plenty of energy here, and the divided strings with basses set to the rear left give openness to textures. However, the strings are not opulent and the trumpets are often piercing. It would be fair to say that Kubelik conducted Mahler as if it were Mozart!

As it happens, in the most controversial of his readings, No. 6, the DG is preferable to the Audite, where Kubelik projects little empathy with its slow movement and where the Scherzo is less cohesive. The real problem is that the very fast speed for (I) affects ail subsequent tempo relationships. Nor does the finale on No. 3, one of the glories of the DG cycle, quite have the same radiance; the singers are the same, the Tölz Boys making a sound one imagines Mahler must have heard in his head, and this performance predates the DG by one month. Nevertheless, these newer issues of Nos 2 and 3 are worth hearing, the ‘Resurrection’ not least for Brigitte Fassbaender’s account of ‘Urlicht’.

Nowadays every orchestra visiting London seems to programme Mahler’s Fifth Symphony as a showpiece, but in 1951 (when Bruno Walter’s 78rpm set was the collector’s only choice) a performance would surely have been uncommon even at the Concertgebouw – Mengelberg was prohibited from conducting in Holland from 1946 until he died that year. Although the start of (V) is marred by horns, this is an interesting, well executed account with a weightier sound, from what one can surmise through the inevitable dimness – the last note of (I) is almost inaudible. The three versions vary sufficiently to quote true timings (none is given by Tahra): (I) 11m 34s/12m 39s/11m 35s (Tahra/Audite/DG); (II) 13m/14m 52s/13m 52s; (III) 15m 56s/17m 54s/17m 23s; (IV) 9m 24s/10m 24s/9mm 44s); (V) 14m 26s/14m 57s/15m 29s. The live Munich version is tidier than on DG; the spectral imagery in (III) is heavier in effect, too; and in the Adagietto the dynamic and phrasing shadings and poetic quality of the string playing also give the live performance the edge. Towards the end of the finale, and elsewhere, the engineers reduced dynamic levels.

Tahra’s booklet comprises an untidily set-out synopsis of Kubelik’s career. Audite’s have full descriptions of the works with text for Nos 2 and 3, and different back-cover colour portraits of the conductor.

Pizzicato | 10.2002 | Rémy Franck | October 1, 2002 Optimistisches 'Lied von der Erde'

Kubelik hat für die Deutsche Grammophon die Mahler-Symphonien aufgenommen, nicht aber 'Das Lied von der Erde'. Nachdem uns etliche derMehr lesen

Audite legt also mit dieser CD eine in der Interpretationsgeschichte vom 'Lied von der Erde' eine essentielle Interpretation vor, die unsere Sicht auf dieses von Mahler als sein persönlichstes Werk bezeichnete Komposition völlig erneuert.

International Record Review | 10/2002 | Christopher Breuning | October 1, 2002

The German firm Audite has given us not only this near complete live cycle of Mahler symphonies (sans 4 or 8), but valuable Kubelik/Curzon readings ofMehr lesen

Recorded between 1967 and 1971, Kubelik's DG cycle has been at budget price for some time now (Collector 463 738-2, ten discs) and the Audite alternatives of 1, 5 and 7 have been in the shops for months. The NHK-recorded Ninth (Audite 95471), made during a 1975 Tokyo visit by the Bavarian RSO, was reviewed in CRC, Spring 2001 (I found the sound unfocused and the brass pinched in sound, but welcomed in particular playing ‘ablaze’ after the visionary episode in the Rondo burleske and a crowning finale). No. 1 on DG is widely admired but this 1979 version is more poetic still, wonderfully so in the introduction and trio at (II). There is something of a pal of resonance in place of applause, cut from all these Audite transfers. In No.7 the balance is more airy than DG’s multi-miked productions, and (as in No.5) Kubelik sounds less constrained than when working under studio conditions, although rhythm in the opening bars of (II) goes awry and the very opening note is succeeded by a sneeze! The disturbing and more shadowy extremes are more vividly characterised, the finale a riotous display.

Some critics feet that Kubelik gives us ‘Mahler-lite’ which may seem so in comparison with, say, Chailly's Decca cycle or the recent BPO/Abbado Third on DG – not to mention Bernstein's. But there is plenty of energy here, and the divided strings with basses set to the rear left give openness to textures. However, the strings are not opulent and the trumpets are often piercing. It would be fair to say that Kubelik conducted Mahler as if it were Mozart!

As it happens, in the most controversial of his readings, No. 6, the DG is preferable to the Audite, where Kubelik projects little empathy with its slow movement and where the Scherzo is less cohesive. The real problem is that the very fast speed for (I) affects ail subsequent tempo relationships. Nor does the finale of No. 3. one of the glories of the DG cycle, quite have that same radiance; the singers are the same, the Tölz Boys making a sound one imagines Mahler must have beard in his head, and this performance predates the DG by one month. Nevertheless, these newer issues of Nos 2 and 3 are worth hearing, the ‘Resurrection’ not least for Brigitte Fassbaender's account of the ‘Urlicht’.

Nowadays, every orchestra visiting London seems to programme Mahler's Fifth Symphony as a Showpiece, but in 1951 (when Bruno Walter's 78rpm set was the collector's only choice) a performance would surely have been uncommon even at the Concertgebouw – Mengelberg was prohibited from conducting in Holland from 1946 until he died that year. Although the start of (V) is marred by the horns, this is an interesting, well executed account with a weightier sound, from what one can surmise through the inevitable dimness – the last note of (I) is almost inaudible. The three versions vary sufficiently to quote true timings (none is given by Tahra): (I) 11m 34s/12m 39s/11m 35s (Tahra/Audite/DG); (II) 13m/14m 52s/13m 52s; (III) 15m 56s/17m 54s/17m 23s; (IV) 9m 24s/10m 24s/9m 44s); (V) 14m 26s/14m 57s/15m 29s. The live Munich version is tidier than on DG; the spectral imagery in (III) is

heavier in effect, too; and in the Adagietto the dynamic and phrasing shadings and poetic quality of the string playing also give the live performance the edge. Towards the end of the finale, and elsewhere the engineers reduced dynamic levels.

Tahra's booklet comprises an untidily set-out synopsis of Kubelik's career. Audite's have full description of the works with texts for Nos 2 and 3, and different back-cover colour portraits of the conductor.

Classic Record Collector | 10/2002 | Christopher Breunig | October 1, 2002

The German firm Audite has given us not only this near complete live cycle of Mahler symphonies (sans 4 or 8), but valuable Kubelik/Curzon readings ofMehr lesen

Recorded between 1967 and 1971, Kubelik’s DG cycle has been at budget price for some time now and the Audite alternatives of 1, 5 and 7 have been in the shops for months. The NHK-recorded Ninth, made during a 1975 Tokyo visit by the Bavarian RSO, was reviewed in CRC, Spring 2001 (I found the sound unfocused and the brass pinched in sound, but welcomed in particular playing ‘ablaze’ after the visionary episode in the Rondo burleske and a crowning final). No. 1 in DG is widely admired but this 1979 version is more poetic still, wonderfully so in the introduction and trio at (II). There is something of a pall of resonance in place of applause, cut from all these Audite transfers. In No. 7 the balance is more airy than DG’s multi-miked productions, and (as in No. 5) Kubelik sounds less constrained than when working under studio conditions, although rhythm in the opening bars of (II) goes awry and the very opening note is succeeded by a sneeze! The disturbing and more shadowy extremes are more vividly characterized, the finale a riotous display.

Some critics feel that Kubelik gives us ‘Mahler-lite’, which may seem in comparison with, say, Chailly’s Decca cycle or the recent BPO/Abbado Third on DG – not to mention Bernstein’s. But there is plenty of energy here, and the divided strings with basses set to the rear left give openness to textures. However, the strings are not opulent and the trumpets are often piercing. It would be fair to say that Kubelik conducted Mahler as if it were Mozart!

As it happens, in the most controversial of his readings, No. 6, the DG is preferable to the Audite, where Kubelik projects little empathy with its slow movement and where the Scherzo is less cohesive. The real problem is that the very fast speed for (I) affects ail subsequent tempo relationships. Nor does the finale on No. 3, one of the glories of the DG cycle, quite have the same radiance; the singers are the same, the Tölz Boys making a sound one imagines Mahler must have heard in his head, and this performance predates the DG by one month. Nevertheless, these newer issues of Nos 2 and 3 are worth hearing, the ‘Resurrection’ not least for Brigitte Fassbaender’s account of ‘Urlicht’.

Nowadays every orchestra visiting London seems to programme Mahler’s Fifth Symphony as a showpiece, but in 1951 (when Bruno Walter’s 78rpm set was the collector’s only choice) a performance would surely have been uncommon even at the Concertgebouw – Mengelberg was prohibited from conducting in Holland from 1946 until he died that year. Although the start of (V) is marred by horns, this is an interesting, well executed account with a weightier sound, from what one can surmise through the inevitable dimness – the last note of (I) is almost inaudible. The three versions vary sufficiently to quote true timings (none is given by Tahra): (I) 11m 34s/12m 39s/11m 35s (Tahra/Audite/DG); (II) 13m/14m 52s/13m 52s; (III) 15m 56s/17m 54s/17m 23s; (IV) 9m 24s/10m 24s/9mm 44s); (V) 14m 26s/14m 57s/15m 29s. The live Munich version is tidier than on DG; the spectral imagery in (III) is heavier in effect, too; and in the Adagietto the dynamic and phrasing shadings and poetic quality of the string playing also give the live performance the edge. Towards the end of the finale, and elsewhere, the engineers reduced dynamic levels.

Tahra’s booklet comprises an untidily set-out synopsis of Kubelik’s career. Audite’s have full descriptions of the works with text for Nos 2 and 3, and different back-cover colour portraits of the conductor.

Classic Record Collector | 10/2002 | Christopher Breunig | October 1, 2002

The German firm Audite has given us not only this near complete live cycle of Mahler symphonies (sans 4 or 8), but valuable Kubelik/Curzon readings ofMehr lesen

Recorded between 1967 and 1971, Kubelik’s DG cycle has been at budget price for some time now and the Audite alternatives of 1, 5 and 7 have been in the shops for months. The NHK-recorded Ninth, made during a 1975 Tokyo visit by the Bavarian RSO, was reviewed in CRC, Spring 2001 (I found the sound unfocused and the brass pinched in sound, but welcomed in particular playing ‘ablaze’ after the visionary episode in the Rondo burleske and a crowning final). No. 1 in DG is widely admired but this 1979 version is more poetic still, wonderfully so in the introduction and trio at (II). There is something of a pall of resonance in place of applause, cut from all these Audite transfers. In No. 7 the balance is more airy than DG’s multi-miked productions, and (as in No. 5) Kubelik sounds less constrained than when working under studio conditions, although rhythm in the opening bars of (II) goes awry and the very opening note is succeeded by a sneeze! The disturbing and more shadowy extremes are more vividly characterized, the finale a riotous display.

Some critics feel that Kubelik gives us ‘Mahler-lite’, which may seem in comparison with, say, Chailly’s Decca cycle or the recent BPO/Abbado Third on DG – not to mention Bernstein’s. But there is plenty of energy here, and the divided strings with basses set to the rear left give openness to textures. However, the strings are not opulent and the trumpets are often piercing. It would be fair to say that Kubelik conducted Mahler as if it were Mozart!

As it happens, in the most controversial of his readings, No. 6, the DG is preferable to the Audite, where Kubelik projects little empathy with its slow movement and where the Scherzo is less cohesive. The real problem is that the very fast speed for (I) affects ail subsequent tempo relationships. Nor does the finale on No. 3, one of the glories of the DG cycle, quite have the same radiance; the singers are the same, the Tölz Boys making a sound one imagines Mahler must have heard in his head, and this performance predates the DG by one month. Nevertheless, these newer issues of Nos 2 and 3 are worth hearing, the ‘Resurrection’ not least for Brigitte Fassbaender’s account of ‘Urlicht’.

Nowadays every orchestra visiting London seems to programme Mahler’s Fifth Symphony as a showpiece, but in 1951 (when Bruno Walter’s 78rpm set was the collector’s only choice) a performance would surely have been uncommon even at the Concertgebouw – Mengelberg was prohibited from conducting in Holland from 1946 until he died that year. Although the start of (V) is marred by horns, this is an interesting, well executed account with a weightier sound, from what one can surmise through the inevitable dimness – the last note of (I) is almost inaudible. The three versions vary sufficiently to quote true timings (none is given by Tahra): (I) 11m 34s/12m 39s/11m 35s (Tahra/Audite/DG); (II) 13m/14m 52s/13m 52s; (III) 15m 56s/17m 54s/17m 23s; (IV) 9m 24s/10m 24s/9mm 44s); (V) 14m 26s/14m 57s/15m 29s. The live Munich version is tidier than on DG; the spectral imagery in (III) is heavier in effect, too; and in the Adagietto the dynamic and phrasing shadings and poetic quality of the string playing also give the live performance the edge. Towards the end of the finale, and elsewhere, the engineers reduced dynamic levels.

Tahra’s booklet comprises an untidily set-out synopsis of Kubelik’s career. Audite’s have full descriptions of the works with text for Nos 2 and 3, and different back-cover colour portraits of the conductor.

Répertoire | No 161 | Gérard Belvire | October 1, 2002

Avec Bernstein, Solti et Haitink, Kubelik fait partie des chefs «Mehr lesen

Classic Record Collector | 10/2002 | Christopher Breunig | October 1, 2002

The German firm Audite has given us not only this near complete live cycle of Mahler symphonies (sans 4 or 8), but valuable Kubelik/Curzon readings ofMehr lesen

Recorded between 1967 and 1971, Kubelik’s DG cycle has been at budget price for some time now and the Audite alternatives of 1, 5 and 7 have been in the shops for months. The NHK-recorded Ninth, made during a 1975 Tokyo visit by the Bavarian RSO, was reviewed in CRC, Spring 2001 (I found the sound unfocused and the brass pinched in sound, but welcomed in particular playing ‘ablaze’ after the visionary episode in the Rondo burleske and a crowning final). No. 1 in DG is widely admired but this 1979 version is more poetic still, wonderfully so in the introduction and trio at (II). There is something of a pall of resonance in place of applause, cut from all these Audite transfers. In No. 7 the balance is more airy than DG’s multi-miked productions, and (as in No. 5) Kubelik sounds less constrained than when working under studio conditions, although rhythm in the opening bars of (II) goes awry and the very opening note is succeeded by a sneeze! The disturbing and more shadowy extremes are more vividly characterized, the finale a riotous display.

Some critics feel that Kubelik gives us ‘Mahler-lite’, which may seem in comparison with, say, Chailly’s Decca cycle or the recent BPO/Abbado Third on DG – not to mention Bernstein’s. But there is plenty of energy here, and the divided strings with basses set to the rear left give openness to textures. However, the strings are not opulent and the trumpets are often piercing. It would be fair to say that Kubelik conducted Mahler as if it were Mozart!

As it happens, in the most controversial of his readings, No. 6, the DG is preferable to the Audite, where Kubelik projects little empathy with its slow movement and where the Scherzo is less cohesive. The real problem is that the very fast speed for (I) affects ail subsequent tempo relationships. Nor does the finale on No. 3, one of the glories of the DG cycle, quite have the same radiance; the singers are the same, the Tölz Boys making a sound one imagines Mahler must have heard in his head, and this performance predates the DG by one month. Nevertheless, these newer issues of Nos 2 and 3 are worth hearing, the ‘Resurrection’ not least for Brigitte Fassbaender’s account of ‘Urlicht’.