"Mich berührt es ja immer seltsam, dass die meisten, wenn sie von Natur sprechen, nur immer an Blumen, Vöglein, Waldesluft denken. Den Gott Dionysos, den großen Pan, kennt niemand. So, da haben Sie schon eine Art Programm, wie ich Musik mache." Gustav Mahlers eigene Worte in einem Brief...mehr

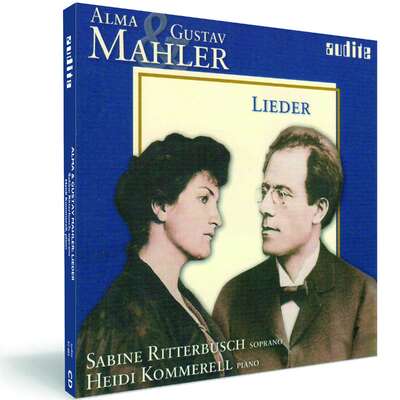

"Mich berührt es ja immer seltsam, dass die meisten, wenn sie von Natur sprechen, nur immer an Blumen, Vöglein, Waldesluft denken. Den Gott Dionysos, den großen Pan, kennt niemand. So, da haben Sie schon eine Art Programm, wie ich Musik mache." Gustav Mahlers eigene Worte in einem Brief...

Details

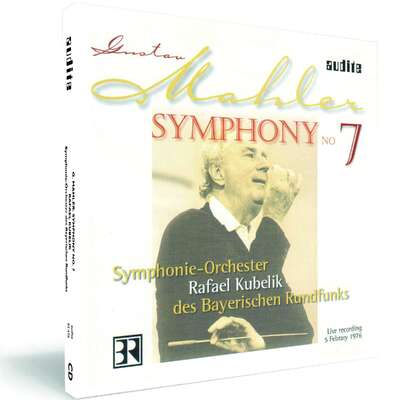

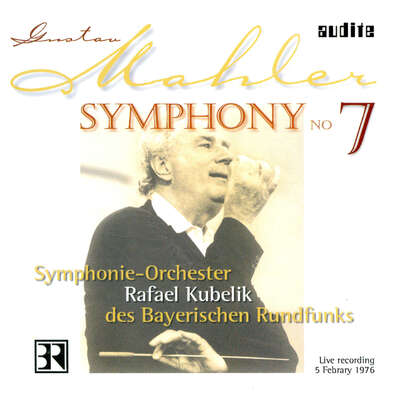

| Gustav Mahler: Symphony No. 7 | |

| Artikelnummer: | 95.476 |

|---|---|

| EAN-Code: | 4009410954763 |

| Preisgruppe: | BCB |

| Veröffentlichungsdatum: | 1. Januar 2001 |

| Spielzeit: | 72 min. |

Informationen

"Mich berührt es ja immer seltsam, dass die meisten, wenn sie von Natur sprechen, nur immer an Blumen, Vöglein, Waldesluft denken. Den Gott Dionysos, den großen Pan, kennt niemand. So, da haben Sie schon eine Art Programm, wie ich Musik mache."

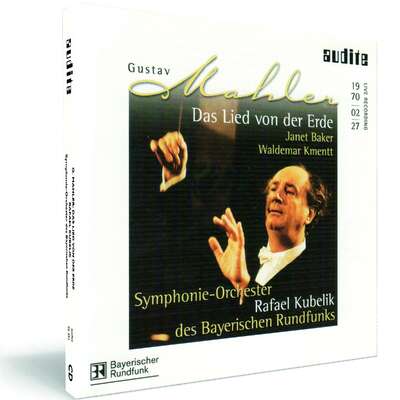

Gustav Mahlers eigene Worte in einem Brief an einen Freund belegen: In seiner 7. Symphonie strebt er wohl eine Lobpreisung von pantheistischem Naturgefühl an, doch nicht im Sinne einer romantischen Idylle. Das Ergebnis Mahlerscher Naturbetrachtung ist äußerst gebrochen und komplex. Das Werk erscheint in einer Live-Aufnahme aus dem Herkules-Saal der Residenz in München vom 05. Februar 1976.Besprechungen

WETA fm | Saturday, 11.28.09, 10:00 am | Jens F. Laurson | 28. November 2009

Mahler’s Seventh Symphony is a forbidding work that can baffle theMehr lesen

Wiener Zeitung | Samstag, 05. Februar 2005 | Edwin Baumgartner | 5. Februar 2005 Kubelik: Mahler-Symphonien 6, 7 und 8

Rafael Kubelik war der Prototyp des hochintelligenten und dabeiMehr lesen

levante | A.Gascó | 14. November 2003 Un Mahler muy bien concebido, tocado en vivo

Rafael Kubelik grabó con su orquesta de la Radioifusión Bávara entreMehr lesen

CD Compact | n°169 (octobre 2003) | Benjamín Fontvelia | 1. Oktober 2003 Rafael Kubelik/Audite

Sin la aparatosa presencia mediática de Karajan y Bernstein, en su rincónMehr lesen

Scherzo | N° 179, Octubre 2003 | Enrique Pérez Adrián | 1. Oktober 2003

Magnífica recreación instrumental, conceptual y expresiva, otro soberbioMehr lesen

El País

| 19.04.2003 | Javier Pérez Senz | 19. April 2003

Kubelik, en el corazón de Mahler

Dos sinfonías de Gustav Mahler grabadas en vivo abren la edición que el sello Audite dedica al director checo Rafael Kubelik, uno de los grandes mahlerianos de la historia.

[...] dirige el célebre adagietto con un encendido lirismo y una intensidad que hipnotiza al oyente –, situándose entre las mejores de la discografía.Mehr lesen

Die Rheinpfalz | 12.02.2003 | Gerhard Tetzlaf | 12. Februar 2003 Idealer Interpret – Livemitschnitte unter Rafael Kubelik

Die Gesamtaufnahme der Sinfonien Gustav Mahlers durch Rafael Kubelik undMehr lesen

International Record Review | 10/2002 | Christopher Breuning | 1. Oktober 2002

The German firm Audite has given us not only this near complete live cycle of Mahler symphonies (sans 4 or 8), but valuable Kubelik/Curzon readings ofMehr lesen

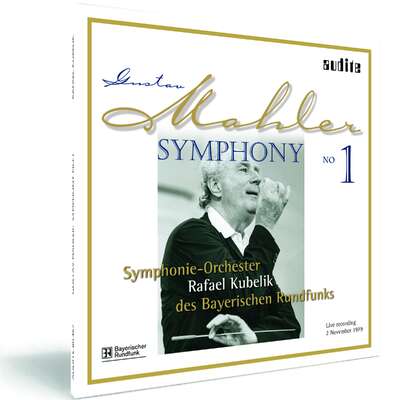

Recorded between 1967 and 1971, Kubelik’s DG cycle has been at budget price for some time now and the Audite alternatives of 1, 5 and 7 have been in the shops for months. The NHK-recorded Ninth, made during a 1975 Tokyo visit by the Bavarian RSO, was reviewed in CRC, Spring 2001 (I found the sound unfocused and the brass pinched in sound, but welcomed in particular playing ‘ablaze’ after the visionary episode in the Rondo burleske and a crowning final). No. 1 in DG is widely admired but this 1979 version is more poetic still, wonderfully so in the introduction and trio at (II). There is something of a pall of resonance in place of applause, cut from all these Audite transfers. In No. 7 the balance is more airy than DG’s multi-miked productions, and (as in No. 5) Kubelik sounds less constrained than when working under studio conditions, although rhythm in the opening bars of (II) goes awry and the very opening note is succeeded by a sneeze! The disturbing and more shadowy extremes are more vividly characterized, the finale a riotous display.

Some critics feel that Kubelik gives us ‘Mahler-lite’, which may seem in comparison with, say, Chailly’s Decca cycle or the recent BPO/Abbado Third on DG – not to mention Bernstein’s. But there is plenty of energy here, and the divided strings with basses set to the rear left give openness to textures. However, the strings are not opulent and the trumpets are often piercing. It would be fair to say that Kubelik conducted Mahler as if it were Mozart!

As it happens, in the most controversial of his readings, No. 6, the DG is preferable to the Audite, where Kubelik projects little empathy with its slow movement and where the Scherzo is less cohesive. The real problem is that the very fast speed for (I) affects ail subsequent tempo relationships. Nor does the finale on No. 3, one of the glories of the DG cycle, quite have the same radiance; the singers are the same, the Tölz Boys making a sound one imagines Mahler must have heard in his head, and this performance predates the DG by one month. Nevertheless, these newer issues of Nos 2 and 3 are worth hearing, the ‘Resurrection’ not least for Brigitte Fassbaender’s account of ‘Urlicht’.

Nowadays every orchestra visiting London seems to programme Mahler’s Fifth Symphony as a showpiece, but in 1951 (when Bruno Walter’s 78rpm set was the collector’s only choice) a performance would surely have been uncommon even at the Concertgebouw – Mengelberg was prohibited from conducting in Holland from 1946 until he died that year. Although the start of (V) is marred by horns, this is an interesting, well executed account with a weightier sound, from what one can surmise through the inevitable dimness – the last note of (I) is almost inaudible. The three versions vary sufficiently to quote true timings (none is given by Tahra): (I) 11m 34s/12m 39s/11m 35s (Tahra/Audite/DG); (II) 13m/14m 52s/13m 52s; (III) 15m 56s/17m 54s/17m 23s; (IV) 9m 24s/10m 24s/9mm 44s); (V) 14m 26s/14m 57s/15m 29s. The live Munich version is tidier than on DG; the spectral imagery in (III) is heavier in effect, too; and in the Adagietto the dynamic and phrasing shadings and poetic quality of the string playing also give the live performance the edge. Towards the end of the finale, and elsewhere, the engineers reduced dynamic levels.

Tahra’s booklet comprises an untidily set-out synopsis of Kubelik’s career. Audite’s have full descriptions of the works with text for Nos 2 and 3, and different back-cover colour portraits of the conductor.

Classic Record Collector | 10/2002 | Christopher Breunig | 1. Oktober 2002

The German firm Audite has given us not only this near complete live cycle of Mahler symphonies (sans 4 or 8), but valuable Kubelik/Curzon readings ofMehr lesen

Recorded between 1967 and 1971, Kubelik’s DG cycle has been at budget price for some time now and the Audite alternatives of 1, 5 and 7 have been in the shops for months. The NHK-recorded Ninth, made during a 1975 Tokyo visit by the Bavarian RSO, was reviewed in CRC, Spring 2001 (I found the sound unfocused and the brass pinched in sound, but welcomed in particular playing ‘ablaze’ after the visionary episode in the Rondo burleske and a crowning final). No. 1 in DG is widely admired but this 1979 version is more poetic still, wonderfully so in the introduction and trio at (II). There is something of a pall of resonance in place of applause, cut from all these Audite transfers. In No. 7 the balance is more airy than DG’s multi-miked productions, and (as in No. 5) Kubelik sounds less constrained than when working under studio conditions, although rhythm in the opening bars of (II) goes awry and the very opening note is succeeded by a sneeze! The disturbing and more shadowy extremes are more vividly characterized, the finale a riotous display.

Some critics feel that Kubelik gives us ‘Mahler-lite’, which may seem in comparison with, say, Chailly’s Decca cycle or the recent BPO/Abbado Third on DG – not to mention Bernstein’s. But there is plenty of energy here, and the divided strings with basses set to the rear left give openness to textures. However, the strings are not opulent and the trumpets are often piercing. It would be fair to say that Kubelik conducted Mahler as if it were Mozart!

As it happens, in the most controversial of his readings, No. 6, the DG is preferable to the Audite, where Kubelik projects little empathy with its slow movement and where the Scherzo is less cohesive. The real problem is that the very fast speed for (I) affects ail subsequent tempo relationships. Nor does the finale on No. 3, one of the glories of the DG cycle, quite have the same radiance; the singers are the same, the Tölz Boys making a sound one imagines Mahler must have heard in his head, and this performance predates the DG by one month. Nevertheless, these newer issues of Nos 2 and 3 are worth hearing, the ‘Resurrection’ not least for Brigitte Fassbaender’s account of ‘Urlicht’.

Nowadays every orchestra visiting London seems to programme Mahler’s Fifth Symphony as a showpiece, but in 1951 (when Bruno Walter’s 78rpm set was the collector’s only choice) a performance would surely have been uncommon even at the Concertgebouw – Mengelberg was prohibited from conducting in Holland from 1946 until he died that year. Although the start of (V) is marred by horns, this is an interesting, well executed account with a weightier sound, from what one can surmise through the inevitable dimness – the last note of (I) is almost inaudible. The three versions vary sufficiently to quote true timings (none is given by Tahra): (I) 11m 34s/12m 39s/11m 35s (Tahra/Audite/DG); (II) 13m/14m 52s/13m 52s; (III) 15m 56s/17m 54s/17m 23s; (IV) 9m 24s/10m 24s/9mm 44s); (V) 14m 26s/14m 57s/15m 29s. The live Munich version is tidier than on DG; the spectral imagery in (III) is heavier in effect, too; and in the Adagietto the dynamic and phrasing shadings and poetic quality of the string playing also give the live performance the edge. Towards the end of the finale, and elsewhere, the engineers reduced dynamic levels.

Tahra’s booklet comprises an untidily set-out synopsis of Kubelik’s career. Audite’s have full descriptions of the works with text for Nos 2 and 3, and different back-cover colour portraits of the conductor.

Hi Fi Review | Vol. 192, May/June 2002 | 1. Mai 2002

chinesische Rezension siehe PDFMehr lesen

International Record Review | 12/2001 | Graham Simpson | 1. Dezember 2001

Still the enigma among Mahler symphonies, or is it that commentators still miss the point, or that the work as a whole is simply not good music? ThisMehr lesen

A central factor in interpreting the Seventh Symphony is its form, each movement a sonata-rondo derivative that proceeds in circular rather than linear fashion. The outcome: a symphony which repeatedly turns back on itself, tying up loose ends across rather than between movements. Kubelík understands this so that, for instance, the initial Langsam, purposeful rather than indolent, is integral to what follows it. Similarly, the expressive central episode (8'43") is no mere interlude, but a necessary stage in the E/E minor tonal struggle around which the movement pivots. Kubelík catches the emotional ambivalence, if not always the fine irony, of the first Nachtmusik's march fantasy, while the Scherzo not only looks forward (as note writer Erich Mauermann points out) to La valse but also recalls the balletic dislocation of 'Un bal' from Symphonie fantastique. The second Nachtmusik is neither bland nor sentimentalized, just kept moving at a strolling gait, its course barely impeded by moments of chromatic emphasis. The underlying élan of the 'difficult' finale is varied according to each episode, with the reintroduction of earlier material (12'26") felt not as a grafted-on means of unity, but a thematic intensification before the affirmative reprise of the opening music: 'victory' in the completion of the journey rather than in the arrival.

Drawbacks? The extremely high-level radio broadcast, coupled with the frequent sense that Kubelík has rehearsed his players only to the brink of security, gives climactic passages a certain desperate quality — much of the detail is left to fend for itself. The six-note col legno phrase in the second movement is never played the same way twice, while the balance in the fourth movement does the guitar few favours. Yet there is a sense that this is the personal reading Kubelík was unable to achieve in the studio, before he either changed tack or lost the interpretative plot in his bizarrely laboured New York account. In their different ways, Bernstein, Haitink and Rattle are each more 'realized' as interpretations, but overt spontaneity may count for more in this Mahler symphony than any other.

International Record Review | 12/2001 | Graham Simpson | 1. Dezember 2001

Still the enigma among Mahler symphonies, or is it that commentators still miss the point, or that the work as a whole is simply not good music? ThisMehr lesen

A central factor in interpreting the Seventh Symphony is its form, each movement a sonata-rondo derivative that proceeds in circular rather than linear fashion. The outcome: a symphony which repeatedly turns back on itself, tying up loose ends across rather than between movements. Kubelík understands this so that, for instance, the initial Langsam, purposeful rather than indolent, is integral to what follows it. Similarly, the expressive central episode (8'43") is no mere interlude, but a necessary stage in the E/E minor tonal struggle around which the movement pivots. Kubelík catches the emotional ambivalence, if not always the fine irony, of the first Nachtmusik's march fantasy, while the Scherzo not only looks forward (as note writer Erich Mauermann points out) to La valse but also recalls the balletic dislocation of 'Un bal' from Symphonie fantastique. The second Nachtmusik is neither bland nor sentimentalized, just kept moving at a strolling gait, its course barely impeded by moments of chromatic emphasis. The underlying élan of the 'difficult' finale is varied according to each episode, with the reintroduction of earlier material (12'26") felt not as a grafted-on means of unity, but a thematic intensification before the affirmative reprise of the opening music: 'victory' in the completion of the journey rather than in the arrival.

Drawbacks? The extremely high-level radio broadcast, coupled with the frequent sense that Kubelík has rehearsed his players only to the brink of security, gives climactic passages a certain desperate quality — much of the detail is left to fend for itself. The six-note col legno phrase in the second movement is never played the same way twice, while the balance in the fourth movement does the guitar few favours. Yet there is a sense that this is the personal reading Kubelík was unable to achieve in the studio, before he either changed tack or lost the interpretative plot in his bizarrely laboured New York account. In their different ways, Bernstein, Haitink and Rattle are each more 'realized' as interpretations, but overt spontaneity may count for more in this Mahler symphony than any other.

American Record Guide | 6/2001 | Gerald S. Fox | 1. November 2001

As with the Kubelik recording of Mahler's Symphony 2 (July/Aug 2001), this 1976 concert performance of Symphony 7 is not to be confused with his 1970Mehr lesen

Despite the fact that many of the instruments (especially percussion) are scarcely heard, the recording has good sound. There are those who prefer their Mahler underplayed, with emotions held in check. I can recommend this recording to them, but as I have said often in these pages, underplayed, unemotional Mahler is an oxymoron.

Gramophone | Oct. 2001 | Richard Osborne | 1. Oktober 2001

Rafael Kubelik's 1970 Deutsche Grammophon recording of Mahler's Seventh Symphony, made with this same orchestra in this same hall, was and remains asMehr lesen

Kubelik's approach suits the music wonderfully well: the opening movement's mighty oar-stroke, the spectral scherzo, the balmy beneath-the-stars caress of 'Nachtmusik II' (which like the Adagietto of the Fifth Symphony is all the more alluring at a quickish tempo), the finale's quasi-Ivesian revel. I would gather from Jonathan Swain's review of Kubelik's live 1980 New York performance that the reading had put on weight by then. That, or the New York Philharmonic lacked the time or inclination to dip their sound in the refiner's fire.

Happily, this 1976 Bavarian Radio performance is very much the reading as it was, with a comparably fine Herkulessaal recording. What it lacks, alas, is the absolute clarity and consistent impetus of the studio version. Recording these Mahlerian behemoths at a single sitting often ends up this way. In the finale, the playing lacks the freshness - the needle-sharp texturing and edge-of-the-seat excitement - of the studio version.

The studio recording is available only as part of Kubelik's complete 10-CD set of the symphonies (glorious performances of Nos 1, 3 and 7, and nothing that is less than fresh and interesting, all advantageously priced). Younger Mahlerians who can't run to that may care to get a sense of this unique reading of the Seventh from the new Audite CD. Sadly, it isn't cheap; indeed, given its provenance and packing, it's unreasonably dear.

The Lion | Septembre 2001, No 527 | Claude Lamarque | 1. September 2001

Il faut un réel courage et un remarquable directeur artistique pour qu'uneMehr lesen

Pizzicato | 09/2001 | Rémy Franck | 1. September 2001 Kubelik mit impulsivem Mahler

Erstes auffallendes Merkmal dieser Live-Aufnahme der erratischen 7. Symphonie Gustav Mahlers ist die Schnelligkeit, mit der Kubelik die EcksätzeMehr lesen

Stereo | 09/2001 | Egon Bezold | 1. September 2001

Rafael Kubelik galt als profunder Mahler-Interpret. Er war von 1961 bisMehr lesen

Klassik heute | 07/2001 | Benjamin G. Cohrs | 1. Juli 2001

Künstlerisch sind die bislang vorgelegten live-Mitschnitte von MahlersMehr lesen

Rondo | 6/2001 | Oliver Buslau | 1. Juni 2001

Lorbeer + Zitronen

Was Rondo-Kritikern 2001 besonders gefallen und missfallen hat

Meine stille Liebe:<br /> die Wiederveröffentlichungen der Mahler-Sinfonien mitMehr lesen

die Wiederveröffentlichungen der Mahler-Sinfonien mit

www.buch.de | 11.05.2001 | Olaf Behrens | 11. Mai 2001

Die siebte Symphonie von Gustav Mahler erscheint bis heute rätselhaft.Mehr lesen

Classica | Mai 2001 | Stéphane Friédérich | 1. Mai 2001

Il manque encore les Symphonies no 2, no 3, no 6 et no 8 pour que cetteMehr lesen

Monde de la Musique | Mai 2001 | Patrick Szersnovicz | 1. Mai 2001

Avec les quartes empilées de son premier mouvement qui paraissent avoir directement inspiré la Première Symphonie de chambre de Schoenberg etMehr lesen

Après de remarquable Cinquième et Neuvième Symphonies et de splendides Première ( « Choc » ) et Deuxième (idem), toutes quatre enregistrées « live », la firme Audite Schallplatten propose un nouvel inédit de ce cycle Mahler /Kubelik/Radio bavaroise. Plus subtil, plus libre, plus interrogatif et moins uniment fébrile que dans sa version de studio « officiel » de la Septième Symphonie avec la même orchestre (DG, 1970), Rafael Kubelik, dans cet enregistrement du 5 février 1976 réalisé à la Herkulessaal de la Résidence de Munich, concilie la gravité ( premier mouvement ), les élans visionnaires ( trois mouvements médians ) et un refus de toute redondance inutile ( finale ). Assez éloigné du romantisme déchirant de Bernstein I/New York (Sony, « Choc ») comme de la clarté analytique et de la beauté des couleurs de Haitink III/Berlin (Philips, idem), Kubelik allie l’intelligence au lyrisme. Il sait caractériser toutes les musiques, toute l’ambiguïté que l’oeuvre contient sans jamais perdre le fil du parcours, et il magnifie le détail en préservant la cohérence de la progression dramatique. Sans être partout impeccables, les instrumentistes de l’Orchestre de la Radio bavaroise répondent avec vivacité aux impulsions du chef, qui concilie les contraires avec clairvoyance.

Répertoire | Mai 2001 | Christophe Huss | 1. Mai 2001

La 7e Symphonie est l'un des points culminants de l'intégrale officielleMehr lesen

Rondo | 19.04.2001 | Thomas Schulz | 19. April 2001

Mahlers "verflixte Siebte", die so vielen Interpreten und Exegeten RätselMehr lesen

Die Presse | Nr. 15.940 | Wilhelm Sinkovicz | 7. April 2001

Rafael Kubelik hat seinen Mahler-Zyklus mit dem Symphonieorchester desMehr lesen

Fono Forum | 4/01 | Gregor Willmes | 1. April 2001 Mahler ohne Manierismen

Im August jährt sich der Todestag von Rafael Kubelik zum fünften Mal. Die kleine, aber feine Schallplattenfirma audite pflegt sein AndenkenMehr lesen

Der Durchbruch Gustav Mahlers fand nicht im Konzertsaal statt. Zwar gab es nach seinem Tod einige Dirigenten, die wie Willem Mengelberg, Otto Klemperer und Bruno Walter Mahler noch kennen gelernt hatten und sich nachdrücklich auch im Konzertsaal für seine Sinfonien einsetzten. Doch verdankt Mahler mit Sicherheit seine Popularität zum großen Teil der Stereo-Schallplatte. Seine Sinfonien schienen wie geschaffen dazu, die Möglichkeiten der Studio-Technik darzustellen. So klingen die riesigen Sinfonien auf Tonträger oftmals sogar transparenter, als sie es im Konzertsaal je vermögen.

Leonard Bernstein war der erste, der Mitte der 60er Jahre mit dem New York Philharmonic für CBS (heute Sony) eine Gesamtaufnahme der Mahlerschen Sinfonien schuf, allerdings ohne das Adagio der unvollendeten Zehnten. Ihm folgte Rafael Kubelik, der mit dem Symphonieorchester des Bayerischen Rundfunks zwischen 1967 und 1971 im Herkules-Saal der Münchener Residenz alle Neune und den Adagio-Satz der Zehnten aufzeichnen ließ. Nur kurze Zeit später erschienen noch Gesamtaufnahmen von Bernard Haitink (Philips) und Georg Solti (Decca).

Ingo Harden zog im Dezember 1971 im Fono Form folgendes Fazit bezüglich der Kubelik-Aufnahmen: "Alles in allem: Der zweite vollständige Mahler-Zyklus hat in der Reihe der Mahler-Interpretationen der Gegenwart sein durchaus eigenes Profil, da sich von Bernsteins Aufnahmen durch ein Weniger an Leidenschaft und Pathos, ein Mehr an orchestraler Detailarbeit, einen helleren Grundton und eine emotional mehr den Mittelkurs haltende Darstellung unterscheidet." Harden stellte das Bild von Kubeliks "böhmischen Musikantentum" infrage, ohne es ganz abzustreiten, lobte darüber hinaus besonders die "sehr subtil und genau alle Klangfarben der Partituren aufschlüsselnden Aufführungen". In beidem ist Harden wohl Recht zu geben, wobei man nach meinem Dafürhalten allerdings Kubeliks tschechischen Wurzeln auch nicht unterschätzen soll, obwohl er sich (worauf Francis Drésel in seinem Aufsatz "Rafael Kubelik - Musiker und Poet" überzeugend hingewiesen hat) wie Mahler nach und nach "germanisiert" hat.

Rafael Kubelik wurde am 29. Juni 1914 in Bychorie bei Prag als Sohn des berühmten Geigen-Virtuosen Jan Kubelik geboren. Er studierte am Konservatorium in Prag Geige, Klavier, Dirigieren und Komposition. Er zählte also zu jener Kategorie von Mahler-Dirigenten, die wie Furtwängler und Klemperer oder wie später Bernstein und Boulez auch als Komponisten hervorgetreten sind. Das lässt vielleicht einerseits besser verstehen, warum Kubelik die musikalischen Zusammen hänge in Mahlers komplexen Sinfonien so einleuchtend darstellen konnte. Andererseits sagt das Komponisten-Dasein allein wieder auch nicht so viel über den Interpretationsstil aus, wenn man etwa an die Unterschiede zwischen Bernsteins expressivem und Boulez' analytischem Zugriff auf Mahler denkt.

Rafael Kubelik lernte Mahlers Sinfonien bereits in seiner Jugend in Prag kennen, zumeist dirigiert von Vaclav Talich,

aber auch von Gastdirigenten wie Bruno Walter, Otto Klemperer und Erich Kleiber. Für Kleibers Aufführung von Mahlers siebter Sinfonie leitete der 24-jährige Kubelik 1938 sogar die ersten Proben mit der Tschechischen Philharmonie.

Schnell machte Kubelik Karriere: 1939 wurde er Musikdirektor der Oper in Brünn, 1942 Leiter der Tschechischen Philharmonie. Später übernahm er Chefpositionen beim Chicago Symphony Orchestra und an den Opernhäusern Covent Garden London und Metropolitan New York. Seine zweite Heimat - nach Prag - wurde allerdings München, wo er von 1961 bis 1971 als Chefdirigent und noch bis 1985 als regelmäßiger Gast das Orchester des Bayerischen Rundfunks zu außergewöhnlichen Erfolgen führte.

Laut Erich Mauermann, dem damaligen Orchesterdirektor, war Kubelik der erste Dirigent der in München einen kompletten Mahler-Zyklus durchführte. Da er Mahlers Werke immer wieder auf den Spielplan setzte, sind einige Konzertmitschnitte erhalten, die jetzt nach und nach bei audite auf CD erscheinen. Friedrich Mauermann, Bruder von Erich Mauermann und mittlerweile in den Ruhestand getretener Ex-Chef von audite Schallplatten, hat die Reihe initiiert und dabei auf das Archiv des Bayerischen Rundfunks zurückgegriffen. Bei den Sinfonien eins, zwei und fünf hatte er sogar jeweils die Auswahl zwischen zwei verschiedenen Mitschnitten. "Wenn mehrere Aufnahmen derselben Sinfonie vorhanden waren", so Mauermann, "habe ich immer die jüngere genommen. Einerseits wegen des besseren Klangbildes, andererseits wegen der musikalischen Qualität. Die Gesamtzeiten der jüngeren Aufnahmen sind generell länger als die der älteren. Die Musik atmet mehr."

Die bisher veröffentlichten Mitschnitte der Sinfonien eins, zwei, fünf, sieben und neun stammen aus den Jahren 1975 und 1982 und wurden bis auf die neunte alle im Münchner Herkules Saal aufgenommen. Folgen sollen noch Mitschnitte der Sinfonien drei (1967) und sechs (1968), ebenfalls aus dem Herkules-Saal.

Somit stammen die bis jetzt vorliegenden Aufnahmen aus einer Zeit, die nach den Grammophon-Aufnahmen liegt. Und sucht man nach grundsätzlichen interpretatorischen Unterschieden, so stößt man zuerst auf die von Mauermann erwähnten langsameren Tempi der späteren Fassungen. Die "beiläufige" Schnelligkeit, die man den DG-Einspielungen bisweilen vorgeworfen hat, sind abgelegt. Vor allem in den Adagio- und Andante-Sätzen wählt Kubelik in späteren Jahren langsamere Tempi, beispielsweise im dritten Satz der ersten Sinfonie, aufgenommen am 2. November 1979. "Feierlich und gemessen, ohne zu schleppen" lautet die Satzbezeichnung, die Kubelik genau beachtet. Wunderbar baut er die Spannung auf, spielt das Crescendo aus, das allein durch das ständige Hinzutreten neuer Instrumente erreicht wird. Das Oboensolo ist überaus deutlich phrasiert, bildet im betonten Staccato einen Kontrapunkt zum Legato der Streicher. Das Parodistische des Satzes ist wesentlich besser getroffen als in der DG-Einspielung. Auch das "Ziemlich langsam" (Ziffer 5) wirkt in sich schlüssiger, man meint auf einmal einen Spielmannszug oder eine Klezmer-Kapelle zu hören.

Herrlich sind auch die ersten beiden Sätze des audite-Mitschnitts gelungen: "Wie ein Naturlaut" - kaum ein Dirigent

dürfte Mahlers Vorstellungen beim Beginn des ersten Satzes wohl so gut getroffen haben wie Kubelik in diesem Konzert. Dass die Stelle hier wesentlich überzeugender wirkt als in der DG-Einspielung, liegt auch in der Aufnahmetechnik begründet. Bei der Grammophon klingen die Stimmen isolierter, in der späteren Rundfunk-Aufnahme verschmelzen sie stärker: Das mindert etwas den analytischen Ansatz, verstärkt jedoch die Unmittelbarkeit der Naturstimmung. Hinzu kommt, dass das Orchester, besonders die Bläser, in der späteren Aufnahme noch souveräner wirken als in der ersten. Dass es sich um einen Konzertmitschnitt handelt, geht nirgendwo auf Kosten der künstlerischen Qualität. Das spricht für eine intensive Probenarbeit.

Die wesentlich bessere Aufnahmetechnik ist übrigens ein Charakteristikum, das fast alle audite-Produktionen auszeichnet. Die Konzertmitschnitte besitzen mehr räumliche Tiefe. Während die DG-Aufnahmen sehr auf Transparenz bedacht sind und immer wieder einzelne Instrumente oder Gruppen nach vorn ziehen, meint man bei den Rundfunkmitschnitten, wirklich ein Orchester im Saal der Residenz zu erleben. Und die Live-Aufnahme der neunten Sinfonie aus Tokios Bunka Kaikan Concert Hall klingt im Vergleich deutlich flacher als die Münchner Aufnahmen.

Was Kubeliks Mahler-Aufnahmen auch noch denen bei audite - gelegentlich fehlt, das ist die mitreißende Kraft, mit der sich etwa Bernstein in die schnellen Sätze warf. Das Finale der ersten Sinfonie ("Stürmisch bewegt") beispielsweise oder der zweite Satz der ansonsten interpretatorisch überzeugenden fünften ("Stürmisch bewegt, mit größer Vehemenz") weisen in dieser Hinsicht Defizite auf.

Den stärksten Eindruck der audite-Mitschnitte hinterlassen nicht zufällig jene Sinfonien, die solche Satzcharaktere

weitesgehend aussparen: die zweite und die siebte Sinfonie. So war der 8. Oktober 1982 ein wirklicher Glückstag für die Geschichte der Mahler-Interpretation. Denn Kubelik dirigierte die zweite an diesem Tag wie aus einem Guss: Alles fließt, nichts wirkt forciert im Allegro maestoso. Ein ungemein feinsinniges, schwereloses Musizieren zeichnet das Andante aus. Herrlich setzt Kubelik das Scherzo um. Das böhmisch-mährische Musikantentum - dem Ingo Harden einst so zweifelnd gegenüberstand - ist hier prächtig zu finden. Die Fischpredigt hält Kubelik leider nicht ganz so ironisch wie Bernstein. Dafür hat er mit Brigitte Fassbaender einen Alt, der das "Röschen rot" mit hinreißendem Timbre und klarer, sinnhaltiger Artikulation versieht. Im hervorragend gesteigerten Finale bilden Edith Mathis und Brigitte Fassbaender ein Traumpaar.

Genauso überragend ist die gerade auf CD erschienene siebte Sinfonie gestaltet. Sehr organisch meisterte Kubelik am 5. Februar 1976 die ständigen Tempowechsel im ersten Satz. Zauberhaft, dunkel getönt kommen die Nachtmusiken auf CD daher. Das Scherzo nimmt von Anfang an gefangen und lässt den Hörer nicht mehr los. Selbst das apotheotische Finale, mit dem viele Dirigenten Probleme haben, klingt bei Kubelik sinnvoll. Das Pathos wirkt nicht übertrieben, aber die Zuversicht bleibt.

Fazit: Mit diesen Mahler-Veröffentlichungen ist audite ein großer Wurf gelungen. Und wer bei Kubelik auf den Geschmack gekommen ist, der kann bei demselben Label auch noch hervorragende Mitschnitte von Beethoven- und vor allem Mozart-Konzerten bekommen, die Clifford Curzon mit dem Symphonieorchester des Bayerischen Rundfunks unter Kubelik in der Residenz gegeben hat. Aber Clifford Curzon ist schon wieder ein Thema für sich.

www.ClassicsToday.com | 01.01.2001 | David Hurwitz | 1. Januar 2001

Rafael Kubelik seems to be enjoying a second career since his death, thanksMehr lesen