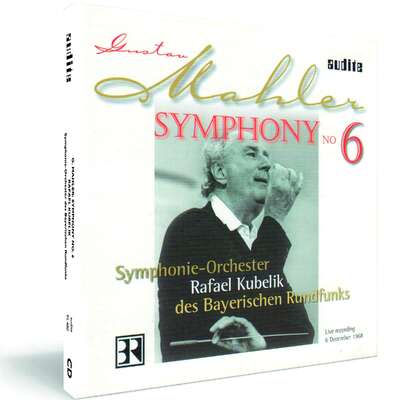

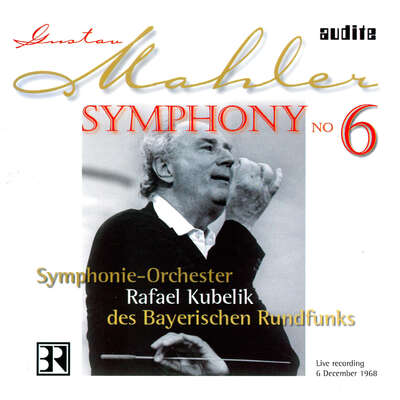

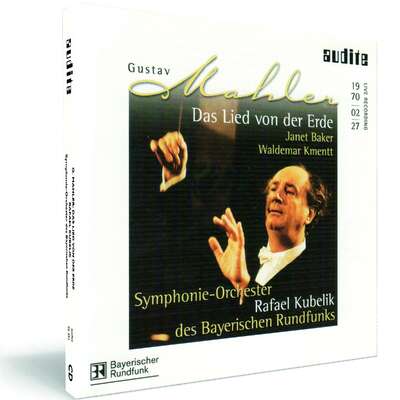

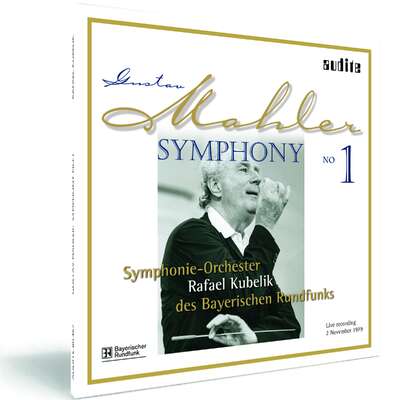

With the Sixth Symphony audite continues its successful Mahler series with the Bavarian Radio Symphony Orchestra under its legendary Music Director Rafael Kubelik. Mahler himself called his Sixth the "Tragic:" it unconditionally duplicates the imaginary hero's path into the final and ultimate...more

"Kubelik dans ce cycle de concerts inédits Mahler / Radio bavaroise se montre plus libre, plus interrogatif, plus fascinant que dans sa version de studio "Officielle", réalisée pourtant à la même époque (DG) ... avec une rare urgence dramatique, il impose une vision à la force hymnique irradiante." (La Monde de la Musique)

Details

| Gustav Mahler: Symphony No. 6 | |

| article number: | 95.480 |

|---|---|

| EAN barcode: | 4009410954800 |

| price group: | BCB |

| release date: | 1. January 2001 |

| total time: | 72 min. |

Informationen

With the Sixth Symphony audite continues its successful Mahler series with the Bavarian Radio Symphony Orchestra under its legendary Music Director Rafael Kubelik. Mahler himself called his Sixth the "Tragic:" it unconditionally duplicates the imaginary hero's path into the final and ultimate downfall. Its instrumentation has grown to gigantic proportions, its expression intensified to the utmost.

The Bavarian Radio Symphony Orchestra tackles this act of power with bravura: enormous expressive power and the highest technical precision are combined in Kubelik's direction to form an impressive sonic experience.

The work is presented in a live recording made on 6.12.1968 from the Herkulessaal of the Munich Residenz.

Reviews

Classica-Répertoire | septembre 2005 | Stéphane Friédérich | September 1, 2005 La Sixième Symphonie de Gustav Mahler

Une soixante d’interprétations étaient en compétition pour cetteMehr lesen

Wiener Zeitung | Samstag, 05. Februar 2005 | Edwin Baumgartner | February 5, 2005 Kubelik: Mahler-Symphonien 6, 7 und 8

Rafael Kubelik war der Prototyp des hochintelligenten und dabeiMehr lesen

www.musicweb-international.com | February 2004 | Tony Duggan | February 1, 2004

Unlike the Audite release of Rafael Kubelik conducting Mahler’s First Symphony in 1971 already reviewed, this "live" recording of the Sixth datesMehr lesen

As I wrote when reviewing the Audite release of the First Symphony, Kubelik’s reputation in Mahler is often misleading. You often see expressions like "understated", "lightweight" and "lyrical" ascribed to it. It’s all relative, of course. True, Kubelik is certainly especially effective when Mahler goes outdoors, back to nature and the "Wunderhorn" moods. But he can also surprise us in those later works where a more astringent, Modernist, fractured approach is called for. This is especially the case if you are prepared to see those crucial aspects through the tinted glass of nature awareness and in context with how he sees the works that go before and after them. No better illustration of his ability to take in the advanced, forward-looking aspect of Mahler's work is provided by his approach to this most Modernist of Mahler’s symphonies.

Kubelik’s performance of the Sixth is astringent and very pro-active. This is the music of a man of action and vigour which, when Mahler wrote it, he certainly was. The first movement is very fast and this certainly stresses the classical basis of this most classically structured movement and therefore, I believe, the nature of the Tragedy embodied. It makes us see Mahler’s "hero" prior to the tragedy that overwhelms him in the last movement in that the pressing forward stresses optimism, a head held high, a corrective to those accounts that seem to want to condemn Mahler’s hero to his doom from the word go, like Barbirolli, for example. It also has the effect of making the music jagged and nervy in the way the episodes tumble past kaleidoscopically. I must praise the Bavarian Radio Orchestra here for managing to hang on so unerringly to the notes most of the time. Of course the DG studio version means that there are no errors of playing but you could argue that if you are going to hear a one-off "live" performance a few mistakes only add to the tension. Remember, however, that Kubelik’s tempi in Mahler are always on average faster than his colleagues and that ought to mitigate a little the speeds encountered here.

The Scherzo is placed second and reinforces the energy, rigour and astringency I remarked on in the first movement. As usual Kubelik is consistent and uncompromising to his vision. Perhaps the speed adopted here does fail to convey the peculiar "gait" of the music and that must be a minus. After this the third movement is beautifully free-flowing and unselfconscious. In fact it is hard to imagine a performance of this movement that could be much better in the way it seems to unfold unassisted, moving in one great breath to a glorious climax that is more effective for being neither under nor over -stated. Notice particularly the nostalgic solo trumpet that is as true a Mahlerian sound as you could wish for. The close-in recording also allows many details to emerge that you may not have hitherto heard so well.

The opening of the last movement is superbly done with trenchancy and harsh detail unflinchingly presented. The main allegro passages emit the same white-hot intensity of the first two movements and yet there remains a controlling mind behind it to guard against the intensity turning into abandonment and so the tension is ratcheted up. There are, as ever, no histrionics from Kubelik. Indeed there is from him just a tunnel-visioned concentration. However, I did begin to feel, particularly after the first hammer blow, that all of this high intensity actually threatens to overwhelm the music’s innate poetry where there needs to be a degree more flexibility, a degree more humanity. That this impression crucially impedes the listener’s ability to notice contrasting passages where you could reflect on what has gone and what might be to come. I suppose you could say that Kubelik allows no time to catch the breath and I really think there should be some. In fact I think much the same can be said about the first two movements under Kubelik but that it takes the experience of the fourth movement pitched at this pace to really bring this home. The Coda, where the trombone section intones a funeral oration over the remains of the fallen hero is, however, under Kubelik an extraordinary sound with a degree of vibrato allowed to the players that chills to the marrow. That, at least, is deeply moving and well worth waiting for even if my overall verdict on Kubelik in this whole symphony is that it falls short of the greatest.

In the end I am left with the feeling that this is a partial picture of the Sixth, albeit an impressive one, but still a partial one which leaves us unsatisfied. I would advise you to turn to Thomas Sanderling on RS which I deal with in my Mahler recordings survey or Gunther Herbig whose recording on Berlin Classics I nominated a Record of the Month, there is also Mariss Jansons on LSO Live whose recent recording impressed me greatly and Michael Gielen on Hänssler. Look to all of those those first.

Rafael Kubelik views the Sixth as high intensity drama right the way through. A perfectly valid view and thrillingly delivered. But this protean work succeeds when its protean nature is laid out before us and Kubelik, eyes wide open, does not really do that. More space, more weight, more room is needed throughout and at particularly crucial nodal points (the two hammer-blows are too lightweight in preparation and delivery, for example) to really move and impress as this symphony can under those mentioned above.

Kubelik’s Mahler Sixth is a very vivid, though very partial, view of the work.

Badische Zeitung | 18.11.2003 | Heinz W. Koch | November 18, 2003

... Wie spezifisch, ja wie radikal sich Gielens Mahler ausnimmt, erhellt schlagartig, wenn man Rafael Kubeliks dreieinhalb Jahrzehnte alte und vorMehr lesen

Eine gehörige Überraschung gab’s schon einmal – als nämlich die nie veröffentlichten Münchner Funk-„Meistersinger“ von 1967 plötzlich zu haben waren. Jetzt ist es Gustav Mahlers drei Jahre später eingespieltes „Lied von der Erde“, das erstmals über die Ladentische geht. Es gehört zu einer Mahler Gesamtaufnahme, die offenbar vor der rühmlich bekannten bei der Deutschen Grammophon entstand. Zumindest bei den hier behandelten Sinfonien Nr. 3 und Nr. 6 war das der Fall. Beim „Lied von der Erde“ offeriert das Symphonie-Orchester des Bayerischen Rundfunks, dessen Chef Kubelik damals war, ein erstaunlich präsentes, erstaunlich aufgesplittertes Klangbild, das sowohl das Idyllisch-Graziöse hervorkehrt wie das Schwerblütig-Ausdrucksgesättigte mit großem liedsinfonischem Atem erfüllt – eine erstrangige Wiedergabe.

Auch die beiden 1967/68 erarbeiteten Sinfonien erweisen sich als bestechend durchhörbar. Vielleicht geht Kubelik eine Spur naiver vor als die beim Sezieren der Partitur schärfer verfahrenden Dirigenten wie Gielen, bricht sich, wo es geht, das ererbte böhmische Musikantentum zumindest für Momente Bahn. Da staunt einer eher vor Mahler, als dass er ihn zu zerlegen sucht. Wenn es eine Verwandtschaft gibt, dann ist es die zu Bernstein. Das Triumphale der „Dritten“, das Nostalgische an ihr wird nicht als Artefakt betrachtet, sondern „wie es ist“: Emotion zur Analyse. ...

(aus einer Besprechung mit den Mahler-Interpretationen Michael Gielens)

El País

| 19.04.2003 | Javier Pérez Senz | April 19, 2003

Kubelik, en el corazón de Mahler

Dos sinfonías de Gustav Mahler grabadas en vivo abren la edición que el sello Audite dedica al director checo Rafael Kubelik, uno de los grandes mahlerianos de la historia.

[...] dirige el célebre adagietto con un encendido lirismo y una intensidad que hipnotiza al oyente –, situándose entre las mejores de la discografía.Mehr lesen

Die Rheinpfalz | 12.02.2003 | Gerhard Tetzlaf | February 12, 2003 Idealer Interpret – Livemitschnitte unter Rafael Kubelik

Die Gesamtaufnahme der Sinfonien Gustav Mahlers durch Rafael Kubelik undMehr lesen

International Record Review | 10/2002 | Christopher Breuning | October 1, 2002

The German firm Audite has given us not only this near complete live cycle of Mahler symphonies (sans 4 or 8), but valuable Kubelik/Curzon readings ofMehr lesen

Recorded between 1967 and 1971, Kubelik's DG cycle has been at budget price for some time now (Collector 463 738-2, ten discs) and the Audite alternatives of 1, 5 and 7 have been in the shops for months. The NHK-recorded Ninth (Audite 95471), made during a 1975 Tokyo visit by the Bavarian RSO, was reviewed in CRC, Spring 2001 (I found the sound unfocused and the brass pinched in sound, but welcomed in particular playing ‘ablaze’ after the visionary episode in the Rondo burleske and a crowning finale). No. 1 on DG is widely admired but this 1979 version is more poetic still, wonderfully so in the introduction and trio at (II). There is something of a pal of resonance in place of applause, cut from all these Audite transfers. In No.7 the balance is more airy than DG’s multi-miked productions, and (as in No.5) Kubelik sounds less constrained than when working under studio conditions, although rhythm in the opening bars of (II) goes awry and the very opening note is succeeded by a sneeze! The disturbing and more shadowy extremes are more vividly characterised, the finale a riotous display.

Some critics feet that Kubelik gives us ‘Mahler-lite’ which may seem so in comparison with, say, Chailly's Decca cycle or the recent BPO/Abbado Third on DG – not to mention Bernstein's. But there is plenty of energy here, and the divided strings with basses set to the rear left give openness to textures. However, the strings are not opulent and the trumpets are often piercing. It would be fair to say that Kubelik conducted Mahler as if it were Mozart!

As it happens, in the most controversial of his readings, No. 6, the DG is preferable to the Audite, where Kubelik projects little empathy with its slow movement and where the Scherzo is less cohesive. The real problem is that the very fast speed for (I) affects ail subsequent tempo relationships. Nor does the finale of No. 3. one of the glories of the DG cycle, quite have that same radiance; the singers are the same, the Tölz Boys making a sound one imagines Mahler must have beard in his head, and this performance predates the DG by one month. Nevertheless, these newer issues of Nos 2 and 3 are worth hearing, the ‘Resurrection’ not least for Brigitte Fassbaender's account of the ‘Urlicht’.

Nowadays, every orchestra visiting London seems to programme Mahler's Fifth Symphony as a Showpiece, but in 1951 (when Bruno Walter's 78rpm set was the collector's only choice) a performance would surely have been uncommon even at the Concertgebouw – Mengelberg was prohibited from conducting in Holland from 1946 until he died that year. Although the start of (V) is marred by the horns, this is an interesting, well executed account with a weightier sound, from what one can surmise through the inevitable dimness – the last note of (I) is almost inaudible. The three versions vary sufficiently to quote true timings (none is given by Tahra): (I) 11m 34s/12m 39s/11m 35s (Tahra/Audite/DG); (II) 13m/14m 52s/13m 52s; (III) 15m 56s/17m 54s/17m 23s; (IV) 9m 24s/10m 24s/9m 44s); (V) 14m 26s/14m 57s/15m 29s. The live Munich version is tidier than on DG; the spectral imagery in (III) is

heavier in effect, too; and in the Adagietto the dynamic and phrasing shadings and poetic quality of the string playing also give the live performance the edge. Towards the end of the finale, and elsewhere the engineers reduced dynamic levels.

Tahra's booklet comprises an untidily set-out synopsis of Kubelik's career. Audite's have full description of the works with texts for Nos 2 and 3, and different back-cover colour portraits of the conductor.

Classic Record Collector | 10/2002 | Christopher Breunig | October 1, 2002

The German firm Audite has given us not only this near complete live cycle of Mahler symphonies (sans 4 or 8), but valuable Kubelik/Curzon readings ofMehr lesen

Recorded between 1967 and 1971, Kubelik’s DG cycle has been at budget price for some time now and the Audite alternatives of 1, 5 and 7 have been in the shops for months. The NHK-recorded Ninth, made during a 1975 Tokyo visit by the Bavarian RSO, was reviewed in CRC, Spring 2001 (I found the sound unfocused and the brass pinched in sound, but welcomed in particular playing ‘ablaze’ after the visionary episode in the Rondo burleske and a crowning final). No. 1 in DG is widely admired but this 1979 version is more poetic still, wonderfully so in the introduction and trio at (II). There is something of a pall of resonance in place of applause, cut from all these Audite transfers. In No. 7 the balance is more airy than DG’s multi-miked productions, and (as in No. 5) Kubelik sounds less constrained than when working under studio conditions, although rhythm in the opening bars of (II) goes awry and the very opening note is succeeded by a sneeze! The disturbing and more shadowy extremes are more vividly characterized, the finale a riotous display.

Some critics feel that Kubelik gives us ‘Mahler-lite’, which may seem in comparison with, say, Chailly’s Decca cycle or the recent BPO/Abbado Third on DG – not to mention Bernstein’s. But there is plenty of energy here, and the divided strings with basses set to the rear left give openness to textures. However, the strings are not opulent and the trumpets are often piercing. It would be fair to say that Kubelik conducted Mahler as if it were Mozart!

As it happens, in the most controversial of his readings, No. 6, the DG is preferable to the Audite, where Kubelik projects little empathy with its slow movement and where the Scherzo is less cohesive. The real problem is that the very fast speed for (I) affects ail subsequent tempo relationships. Nor does the finale on No. 3, one of the glories of the DG cycle, quite have the same radiance; the singers are the same, the Tölz Boys making a sound one imagines Mahler must have heard in his head, and this performance predates the DG by one month. Nevertheless, these newer issues of Nos 2 and 3 are worth hearing, the ‘Resurrection’ not least for Brigitte Fassbaender’s account of ‘Urlicht’.

Nowadays every orchestra visiting London seems to programme Mahler’s Fifth Symphony as a showpiece, but in 1951 (when Bruno Walter’s 78rpm set was the collector’s only choice) a performance would surely have been uncommon even at the Concertgebouw – Mengelberg was prohibited from conducting in Holland from 1946 until he died that year. Although the start of (V) is marred by horns, this is an interesting, well executed account with a weightier sound, from what one can surmise through the inevitable dimness – the last note of (I) is almost inaudible. The three versions vary sufficiently to quote true timings (none is given by Tahra): (I) 11m 34s/12m 39s/11m 35s (Tahra/Audite/DG); (II) 13m/14m 52s/13m 52s; (III) 15m 56s/17m 54s/17m 23s; (IV) 9m 24s/10m 24s/9mm 44s); (V) 14m 26s/14m 57s/15m 29s. The live Munich version is tidier than on DG; the spectral imagery in (III) is heavier in effect, too; and in the Adagietto the dynamic and phrasing shadings and poetic quality of the string playing also give the live performance the edge. Towards the end of the finale, and elsewhere, the engineers reduced dynamic levels.

Tahra’s booklet comprises an untidily set-out synopsis of Kubelik’s career. Audite’s have full descriptions of the works with text for Nos 2 and 3, and different back-cover colour portraits of the conductor.

Gramophone | 08/2002 | David Gutman | August 1, 2002 Undercharcterised Mahler from Kubelik

Do you remember the 1960s? A time before Mahler symphony series were two-a-penny, when conductors like Abravanel, Bernstein, Haitink and Solti vied toMehr lesen

True, the conductor excels himself in the slow movement. Here you'll find the luminous string tone, natural pacing and inner simplicity of his best work, along with sonic unvarnished wind and brass playing. (Don't forget how unfamiliar this music must have been at the time: the Sixth had to wait until 1966 for its French première). The eccentric booklet notes tell us that this Andante moderato 'takes off the stifling corset that prevents one from breathing freely in the other movements'. This isn't - I think - meant to allude to Kubelik's brisk, inflexible pacing, but I found such an approach problematical, particularly in the first two movements where expressive contrasts are consistently underplayed. Given the overall timing shown above, you may be surprised to discover that Kubelik does in fact make the first movement repeat. Only Neeme Järvi races through the music marked Allegro energico via non troppo (but never mind the qualifier) - at quite such a lick. And although Bernstein runs them close, his famously neurotic march has a rhythmic certainty and an alertness to detail and nuance that elude Kubelik in his headlong dash across country. The generalised élan of the finale is rather undermined by the fluffs and false entries, while its coda serves as an unlikely showcase for brass timbre of a more distinctive and regional variety than is beard from this source today. All in all, a bit of a gabble but a gift for confirmed Kubelik fanciers.

Hi Fi Review | Vol. 192, May/June 2002 | May 1, 2002

chinesische Rezension siehe PDFMehr lesen

Fanfare | May/June 2002 | Christopher Abbot | May 1, 2002

According to the booklet that accompanies this release, Audite has released an almost-complete cycle of the Mahler Symphonies conducted by MaestroMehr lesen

In fact, the performance on this disc would appear to be a concert performance that directly preceded the recording made for DG. It was Kubelik's practice to perform the Symphonies in concert and then to go into the studio (in this case, the same venue as the concert: Munich's Herkulessaal) and record the work for release on disc.

It should come as no surprise, then, that the two performances are nearly identical. The DG version has gained a few seconds per movement, but the differences are negligible. Most noticeable is the slightly more expansive development of the first movement, especially in the ethereal "mountain air" music. Orchestral definition is somewhat clearer on DG too, while there is the occasional lapse in ensemble and intonation on Audite that one forgives in a live performance.

As for the performance, it features many of the attractive characteristics of Kubelik's Mahler. His was a dynamic but somewhat understated approach, mostly free of Bernstein hyperbole and less purely driven than Solti. He shared with Haitink both emotional neutrality and the ability to bring clarity to Mahler's contradictory nature. His Sixth begins in an almost frantic manner with an unnecessary accelerando, but it is certainly energetic; the aforementioned development is atmospheric and is a perfect contrast to the relentlessness of the march. The second movement is possessed of much the same energy, but is leavened with whimsy. Not surprisingly, the Andante is starkly beautiful without being schmaltzy.

The finale strikes a balance between the expressionistic episodes, the mountain reminiscences, and the almost manic attempts to forestall the inevitable. The hammer blows (there are two) are not sharp or dry sounding, but the cowbells and celesta are perfect. The final chord is shattering and well judged.

This release would appear to be superfluous were it not for the fact that Kubelik’s DG recording is available only as part of his complete set, albeit at bargain price. This performance may be no match for the precision of Boulez or the emotional commitment of Tennstedt, and it lacks the overall mastery of Zander. But it is historically important, since it documents the work of a gifted second-generation Mahlerian.

Fono Forum | 4/2002 | Christian Wildhagen | April 1, 2002 Sogkraft

Von Rafael Kubelíks Studio-Zyklus aller Mahler-Sinfonien hieß es oft, er betone die böhmische Seite der Musik – ein allzu billigesMehr lesen

Offenkundig handelt es sich bei den Sinfonien Nr. 3 und Nr. 6 um Aufzeichnungen der Konzerte, die den DG-Aufnahmen vorangingen. Man erlebt alle Höhen und Tiefen von Live-Produktionen: kleinere Patzer und eine im Eifer des Gefechts mitunter nivellierte Dynamik, dafür aber mitreißende Spannungsbögen und eine Natürlichkeit der vorwärts drängenden Agogik, die ihresgleichen sucht. So gehört die „Feurig“ überschriebene Passage im Finale der Sechsten (ab 12’58’’) zu den atemberaubendsten Beispielen eines virtuos-enthemmten Orchesterspiels. Eine fast fatalistische Sogkraft scheint die Musik in ihren Strudel zu ziehen, auch im Andante gönnt Kubelík dem Hörer keine Oase der Entrückung.

Ausgeglichener und überragend in seiner großräumigen Disposition wirkt der Mitschnitt der Dritten, der in jedem Moment von der Persönlichkeit des Dirigenten durchdrungen scheint. Kaum ein Detail bleibt da unausgeleuchtet, und allenfalls das zu grobschlächtige Blech trübt bisweilen das Hochgefühl dieser beeindruckenden Aufführung.

Das Orchester | 4/02 | Kathrin Feldmann | April 1, 2002

Zeit seines Lebens wurde Mahler seitens der Kritiker als größenwahnsinnigMehr lesen

The Independent | February 22, 2002 | Rob Cowan | February 22, 2002

Mahler's massive Sixth Symphony runs the gamut of emotion from courageousMehr lesen

Video Pratique | Fevrier-Mars 2002 | February 1, 2002

Une symphonie marquée par le désespoir absolu, d'une noirceur totale,Mehr lesen

Rondo | 13.12.2001 | Oliver Buslau | December 13, 2001

Als die Zuhörer am Nikolaustag des Jahres 1968 im Münchner HerkulessaalMehr lesen

BBC Music Magazine | December 2001 | David Nice | December 1, 2001

Collectors who like to keep a chamber of horrors in their CD library must not be without Scherchen’s live Mahler Five. Did the Philadelphians knowMehr lesen

klassik.com | 29.11.2001 | Beate Hennenberg | November 29, 2001

Das Label Audite setzt mit vorliegender Aufnahme die erfolgreiche Reihe derMehr lesen

Répertoire | No 151 | Pascal Brissaud | November 1, 2001

La même cas de figure se reproduit à l’encontre de Kubelik, dont auMehr lesen

Monde de la Musique | novembre 2001 | Patrick Szersnovicz | November 1, 2001

Volet central de la grande trilogie instrumentale mahlérienne, la Sixième Symphonie (1903-1904) diffère fort de ses jeux voisines: la plus grandeMehr lesen

rapide d'ombres et de lumières débouchant en catastrophe sur le néant, son gigantesque finale évite la grandiloquence malgré son volume sonore, et l'anecdotique malgré sa durée. Le rythme général des formes s'y apparente à un traitement abrupt des tonalités qui permet une meilleure différenciation plastique des plans harmoniques entre eux. Dans de nombreux passages éclate brusquement un ton de suvageric panique. Mahler n'oubliera jamais dans ses oeuvres ultérieures ce qu'il a accompli dans sa Sixième Symphonie: une lumière particulière braquée sur les contours, l'usage de bizarres, de combinaisons paradoxales de forte et de piano, et surtout une tendance du contrepoint à produire d'inattendues dissonances s'alliant à la polarité majeur-mineur (les contrepoints adoptant le mode opposé à celui des harmonies qui les accompagnent).

En complet accord avec la psychologie dramatique de Mahler, Rafael Kubelik dans cet enregistrement « live » du 6 décembre 1968 à la tête d'un Orchestre de la Radio bavaroise chauffé à blanc évite la grandiloquence, malgré une rare intensité et l'irruption d'outrances dont la grandeur dépasse toute négativité. Comme dans de remarquables Cinquième, Septième et Neuvième Symphonies et de splendides Première (« Choc ») et Deuxième (idem) précédemment parues, Kubelik dans ce cycle de concerts inédits Mahler/Radio bavaroise se montre plus libre, plus interrogatif, plus fascinant que dans sa version de studio « officielle », réalisée pourtant à la même époque (DG). Assez éloigné du romantisme déchirant de Bernstein/New York 1 (Sony, 1967), Neumann/Gewandhaus (Berlin Classics, 1966) et Karajan/Berlin (DG, 1977) comme de la clarté analytique de Szell/Claveland (Sony, « live » 1967) et Boulez/Vienne (DG, 1994) ou de la beauté des couleurs de Haitink/Berlin (Philipps, 1989), Kubelik, à partir d'une économie sel serrée des contrastes, et des gradations dynamiques, renforce le sentiment d'unité architecturale tout en magnifiant la « pureté de glace » (Schoenberg) de l'orchestre de la Sixième et en tirant un profit maximal des rares paliers de détente pour mieux assumer les soixante-treize minutes de tension émotionnelle. Tout en soulignant les nuances et les aspérités avec une rare urgence dramatique, il impose une vision à la force hymnique irradiante.

Pizzicato | 11/01 | Rémy Franck | November 1, 2001 Zwei Mahler-Welten

Weiche Weiten zwischen zwei exzellenten Mahler-Interpretationen liegen können, zeigen diese zwei Einspielungen unter Kubelik und Gielen.<br /> <br /> In derMehr lesen

In der live im Müncher Herkules-Saal gemachten Aufnahme peitscht Kubelik sein Orchester stringent und fanatisch durch die Symphonie, mit einem dramatischen und spannungsgeladenen 'Straight forward'-Musizieren, das streckenweise einen atemlos ekstatischen Charakter annimmt. Diese Unerbittlichkeit resultiert denn auch in schnellen 74 Minuten, welche die insgesamt sehr packend gespielte Symphonie bei Kubelik dauert, während der bedächtige Gielen ganze 10 Minuten mehr braucht. Ein enormer Unterschied!

Gielen macht natürlich weitaus mehr Musik hörbar als Kubelik und erzielt eine ebenfalls starke und ergreifende, ja sogar Frösteln auslösende Spannung aus der intellektuellen Durchdringung heraus und aus einem überaus nuancierten Spiel.

Das Schicksal schlägt bei Gielen ganz anders zu als bei Kubelik, hintergründiger, schauriger und mit ausladend großer Wucht. Und es reflektiert die Mahler-Musik nachfolgend in Bergs prächtig resalisierten 'Drei Orchesterstücken', die im Anschluss erklingen, vor dem Andante aus Schuberts 10. Symphonie, das Brian Newbould nach den 1978 gefundenen Skizzen Schuberts fertig stellte. Gielen dirigiert den Klagegesang sehr emotional, gefühlsintensiver jedenfalls als Mahlers Sechste und Bergs Orchesterstücke und setzt so einen ergreifenden Schlusspunkt hinter Musik, deren dämonischen Charakter er zwingend umsetzt.

In der

Campus Mag | No 61 | November 1, 2001

Ecrite en 1903, cette 6ème symphonie sur les 9 composées par Mahler estMehr lesen

Rondo | 6/2001 | Oliver Buslau | June 1, 2001

Lorbeer + Zitronen

Was Rondo-Kritikern 2001 besonders gefallen und missfallen hat

Meine stille Liebe:<br /> die Wiederveröffentlichungen der Mahler-Sinfonien mitMehr lesen

die Wiederveröffentlichungen der Mahler-Sinfonien mit

www.ClassicsToday.com | 01.01.2000 | David Hurwitz | January 1, 2000

This live Mahler Sixth sheds less light on Kubelik's way with the musicMehr lesen

Bayerische Staatszeitung | 13.06.1968 | aw | June 13, 1971

Ein künstlerisches Ereignis schon als Begebenheiten: denn das '1904Mehr lesen