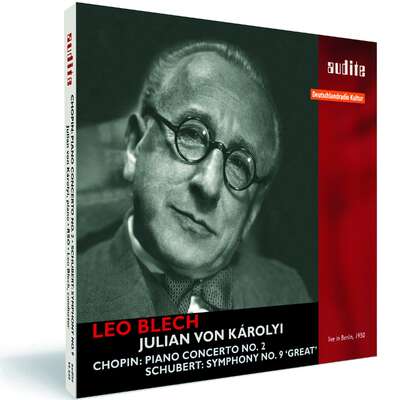

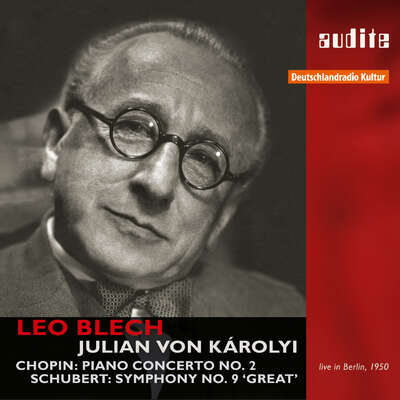

Leo Blech was considered one of the greatest conductors of his time before he was forced in 1937 by the Nazis to emigrate, due to his Jewish faith. His artistic partnership with Julian von Károlyi, one of the leading pianists of his generation, is documented on this CD in a live recording from 1950. Both artists, outstanding interpreters of the twentieth century, are unjustly neglected today.more

Leo Blech was considered one of the greatest conductors of his time before he was forced in 1937 by the Nazis to emigrate, due to his Jewish faith. His artistic partnership with Julian von Károlyi, one of the leading pianists of his generation, is documented on this CD in a live recording from 1950. Both artists, outstanding interpreters of the twentieth century, are unjustly neglected today.

Details

| F. Chopin: Piano Concerto No. 2 & F. Schubert: Symphony ‘The Great’ in C major, D. 944 | |

| article number: | 95.640 |

|---|---|

| EAN barcode: | 4022143956408 |

| price group: | BCB |

| release date: | 26. August 2011 |

| total time: | 78 min. |

Bonus Material

Informationen

The conductor Leo Blech and the pianist Julian von Károlyi, whose live performance of the Chopin Second Piano Concerto given at the Berlin Titania Palast in 1950 is documented on this CD, are nowadays ranked amongst the greatest but unjustly forgotten interpreters of the twentieth century. Blech, whose sophisticated mature reading of Schubert’s Symphony in C major, “The Great”, can also be admired on this recording, had been a leading German conductor since 1908 until he was pushed out of his post by the Nazis in 1933, due to his Jewish faith, and was forced to emigrate. Károlyi, a leading pianist of his generation in the 1950s, was later accused of being routine-driven. His masterful Chopin interpretation demonstrates, however, that his ability to combine musicianship and virtuosity is exemplary even today.

The production is part of our series „Legendary Recordings“ and bears the quality feature „1st Master Release“. This term stands for the excellent quality of archival productions at audite. For all historical publications at audite are based, without exception, on the original tapes from broadcasting archives. In general these are the original analogue tapes, which attain an astonishingly high quality, even measured by today‘s standards, with their tape speed of up to 76 cm/sec. The remastering – professionally competent and sensitively applied – also uncovers previously hidden details of the interpretations. Thus, a sound of superior quality results. CD publications based on private recordings from broadcasts or old shellac records cannot be compared with these.

Reviews

Diverdi Magazin | n°213 (abril 2012) | Arturo Reverter | April 1, 2012

Dos olvidados

Leo Blech y Károlyi en grabación histórica de Audite

La vida es aveces inexplicablemente injusta y deja que una pátina de silencio caiga sobre situaciones o nombres sin aparente razón. Al germano LeoMehr lesen

Este disco, de sonido bastante aceptable, proviene de unas tomas de la RIAS de Berlín realizadas durante un concierto celebrado en cl histórico Titania-Palast el 4 de junio de 1950. La “Sinfonia n° 9” de Schubert se afronta de manera amplia, que no ampulosa, sometida a una fIuctuación constante de tempi, curiosa más que caprichosa, que otorga en todo caso vida al discurso, cuajado de detalles y de accidentes amenos e inesperados. Resuelve Blech estupendamente el problema que siempre acecha a la resolución deI comienzo de la obra, ese Andante que vira inopinadamente a Allegro ma non troppo.

No estamos ante una versión a lo Furtwängler, ya que para ello falta grandeza, humanismo, monumentalidad, pero no andamos lejos. Blech es más lírico y grácil. A la segunda escucha nos identificamos con sus criterios en parte oscilantes pero de rara musicalidad. Que son los que sin duda aplica a la interpretación del “Concierto n° 2” de Chopin, en donde la orquesta se une al teclado con presteza y elasticidad, con finura y sentido del canto, lo que propicia una versión muy rica y ajena al énfasis o al edulcoramiento en la que navega gustoso Károlyi, que demuestra ser un artista de primera, con un toque delicado pero muelle, un sonido exquisito y un fraseo natural ceñido al estilo. Un Chopin de alto rango, cristalino y viril. Buena oportunidad, pues, para el reencuentro o según los casos, el encuentro con dos figuras postergadas. ¿Qué mejor manera para rescatarlas del olvido que ésta?

American Record Guide | 01.03.2012 | David Radcliffe | March 1, 2012

Leo Blech (1871–1958) was a popular and prolific Victor artist in the 1920s and 30s whose career was wrecked by the Nazis late in life. It wasMehr lesen

If the RIAS musicians respond to Blech with obvious enthusiasm, they seem to have had difficulty following his motions, for entrances and balances lack the precision one expects and that Blech obtained in his earlier recordings. It may be just that he was getting old or that there was not enough rehearsal time, but I think I hear something more than that—an orchestra more accustomed to being told exactly what was required of them struggling to follow the lead of a conductor accustomed to a more fluid working relationship with his players. They grasp the idea, but the execution tends to be rugged.

However that may be, the interpretations seem a throwback to the earlier times of Nikisch and Mahler, with untethered tempos, free rubato, and much striving for rhetorical effect: hoary old Leo Blech grabs the listener by the collar and never stops shaking. This can be exhausting in the long Schubert performance, which suffers by comparison to Furtwangler—who used similar devices with a sense of control lacking here. Blech can be heard to better advantage in this symphony in his studio recording, the ancient Victor M 33. But there is a poignancy about this late performance not to be gainsaid: it is not merely the survival but the positive assertion of 19th Century musical values in bomb-shattered Berlin. It was a bold thing for a Jewish conductor to return to Germany after the war (the story is well told in the liner notes) and Blech must have felt that he had important things to convey to a younger generation of listeners. In the Chopin concerto he finds a fit companion in the Hungarian pianist Julian von Karolyi (1914-93) who swoops and teeters and soars in the best old-fashioned virtuoso manner. The broadcast sound is wooly, not much of an improvement on Blech’s early electrics, but the sense of occasion triumphs over all in this moving historical reissue.

Diapason | N° 600, Mars 2012 | Rémy Louis | March 1, 2012

Ce concert donné en juin 1950 au Titania-Palast de Berlin-Steglitz nous ramène à une époque peuplée de fantômes. Très actif à Berlin avant,Mehr lesen

Les variations souvent considérables de tempo sont frappantes – curieusement, Wolfgang Rathert n'en souffle mot dans son superbe texte de présentation. Cela ne surprend pas, génération oblige, chez ce chopinien patenté qu'était Karolyi : doigts agiles, timbre et couleurs très vifs, articulation et ornementation subtiles, narration riche de multiples nuances (une gravure de studio du meme Opus 21) existe chez Emi-Electrola, avec le Philharmonique de Berlin dirigé par Schüchter, mais cherchez aussi ses témoignages DG, Emi, Melodram, Arkadia...).

Certains s'étonneront de cette liberté. Qu'ils écoutent alors la 9e de Schubert, où Blech enchaîne les changements de tempo – qu'il ralentisse ou qu'il accélère! – en lien avec la dramatisation des contrastes, parfois jusqu'à l'emphase... Compositeur d'opéras à succès (Das war Ich, Aschenbrödel, Versiegelt...), il s'approprie le texte sans lui ôter sa clarté. Le résultat? Une lecture espressivo surprenante mais lumineuse, qui échappe et séduit tout à la fois. Ce que Karolyi réalisait si bien dans le Concerto en fa mineur, Blech le prolonge dans ce Schubert qui nous dit certainement encore quelque chose des modes d'interprétations du XIXe•siècle – quasi trentenaire en 1900, il était un musicien d'avant la Sachlichkeit (Objectivité), fût-elle ou non Neue. Peu importe alors les faiblesses contingentes, les pailles instrumentals çà ou là. Dans ce moment d'Histoire, tout vit, chante, progresse avec une spontanéité contagieuse. Les deux témoignages avaient existé séparément en CD (Melodram, Hunt, Archipel...), mais le remastering d'Audite est une nouvelle fois hors concours, bien sûr.

Fanfare | 01.03.2012 | Boyd Pomeroy | March 1, 2012

Another wonderful disc in Audite’s archival RIAS series. Leo Blech is best known for his many fine recordings on 78s before the war; this discMehr lesen

The performance of the “Great C Major” captured here is nothing short of a revelation, extraordinary for a man of any age. The introduction is richly pliable, full of imaginatively molded details and with an arresting quality of “speaking” declamation. In the Allegro ma non troppo, he seems to devour the music whole in long, fluid paragraphs. The tempo is flexible, with an extreme volatility in the expanses of the second theme, accelerating by its end to a speed far beyond the initial Allegro. The long sequences of the development have a rare visceral excitement. Orchestral balances are lean and sharp, and the players’ response to his galvanizing direction has real bite. The Andante con moto bursts with dramatic life and heightened rhetoric—hear the spontaneous volatility of the main theme’s contrasting middle section (Rehearsal A ff.), or the amazing life-or-death intensity with which he invests the two-chord motive at 7 before D, etc. The lyrical second theme is shaped with tactile immediacy. At the movement’s central climax, his accelerando is disconcertingly extreme, yet of a piece with his heightened conception of the whole. The Scherzo is lean and fiery; the Trio forward-pressing with little relaxation. The edifice is capped by a big-boned and weighty finale, flexible within a controlled master tempo, with biting accents and long-breathed shaping of paragraphs. Altogether a fascinating contrast with Furtwängler’s postwar performances of the work, with their very different brand of interpretive freedom, but every bit as compelling.

The Chopin concerto is no less welcome, for a reminder of the quality of the near-forgotten Julian von Károlyi, who plays the work with a rare incisiveness, thrust, and exciting Hungarian rhythmic snap. His sound is on the dry side, using very little pedal, with agile reflexes and precision at high speed (exceptionally clean fioriture). Musical gestures are economical, but there is a coil-spring inner tension to his phrasing, and he has that rare knack of suggesting a lot while seeming to do very little. Blech’s conducting is dynamic and involved (unusually for the time, he plays the opening ritornello complete; curiously, he observes a much shorter cut at the end of the movement).

As usual, Audite’s production values are superb; the sound, transferred from the original master tapes, is of astounding vividness, color, clarity, and dynamic range for its time and provenance. An altogether exceptional disc, and I wouldn’t be too surprised if this were to wind up in my next Want List.

Musica | febbraio 2012 | Giuseppe Rossi | February 1, 2012

La prima cosa che colpisce in questa registrazione di un concerto tenutoMehr lesen

Gramophone | February 2012 | February 1, 2012

Contrasting maestros

Mahler from a Russian in Germany, a pair of German conductors and a British band in Dvořák

At the opposite end of the interpretative spectrum from Böhm's temperate Beethoven is Kyrill Kondrashin's combustible Mahler, the Sixth havingMehr lesen

More musically compelling by far, and surprisingly individualistic, is a performance of Schubert's 'Great' C major Symphony that Leo Blech conducted in Berlin (with the Berlin RIAS SO) in 1950. I expected something fairly traditional, but right from the Andante opening Blech's wide range of tempi renders even Furtwängler straitlaced by comparison, the first movement flying off at a real lick then broadening significantly for the coda until the movement grinds to a halt for the final bars. The welcome coupling features the underrated Hungarian pianist Julian von Károlyi in a supple and sensitive performance of Chopin's Second Piano Concerto, the opening tutti immediately arresting one's attention on account of its sensitive phrasing. This is a peach of a disc, and the sound quality is excellent.

A concert recording of Carl Schuricht conducting the Suisse Romande Orchestra in Brahms's Fourth Symphony also has an engaging freshness about it, especially the finale, where the assortment of tempi is almost as varied as Blech's is for Schubert. But it works, and so, oddly enough given one's expectations, does Schuricht's old-world but animated way with Bach's Second Orchestral Suite, where the flute soloist is Andre Pepin. I had no doubt whatever that Nikolai Malko's 1954 Philharmonia set of Dvořák's Slavonic Dances would prove satisfying and thanks to the Magdalen label we're once again able to enjoy Malko's impeccable musical judgement and the liveliness of the Philharmonia's playing. I'd say that viewed overall this is the finest complete set of the Dances to emerge from within these shores, even in view of fine versions under Dorati, Rodzinski and Schwarz. The vinyl-based transfers are more than acceptable.

Piano News | Januar / Februar I/2012 | Carsten Dürer | January 1, 2012 Virtuosität nicht als Selbstzweck

Noch nicht ganz verklungen sind die Einspielungen des Liszt-Jahres. So gibtMehr lesen

Pizzicato | N° 219 - 1/2012 | Guy Wagner | January 1, 2012 Wertvolles Archivstück

Dies ist eine willkommene Ausgrabung, denn es gibt nicht viele Tondokumente, die uns die Kunst von Leo Blech (1871-1958) verdeutlichen. Leo Blech, alsMehr lesen

Die hier vorliegende Einspielung entstand 1950 mit dem RIAS-Orchester und einem anderen, etwas vergessenen Interpreten, dem ungarischen Pianisten Julian von Karolyi (1914-1993), der wegen seiner technischen Brillanz berühmt und seiner pianistischen Exzesse gefürchtet war. Der rigorosen Stabführung von Blech, der sehr mäßige Tempi benutzt, fügt Karolyi sich erstaunlich willig und gestaltet das f-Moll Konzert von Chopin mit ungemein viel Poesie und Delikatesse, schafft emotionale Höhepunkte und gewinnt dem Finale etwas Tänzerisches ab, das bezaubert.

Blech hat, so heißt es, Schuberts 'große' Symphonie besonders gemocht. Seine feierliche, schon fast behäbig zu bewertende Interpretation liegt in der Wiener romantischen Tradition verankert und führt zu einem besonders schönen Gesang der Bläser des RIAS-Orchesters. Am interessantesten erscheint das Andante con moto, dem Blech eine große Farbigkeit und Lebendigkeit verleiht. Sehr energisch geht er das Scherzo an und rückt es in die Nähe Beethovens, während das Finale zwar rhythmisch prägnant ist, doch etwas an Größe und Elan darbt. Trotzdem ist dies zweifellos ein wertvolles CD-Dokument, dem allerdings das Alter der Aufnahme anzumerken ist.

www.klavier.de

| 26.12.2011 | Sophia Gustorff | December 26, 2011

Mehr Glanz als Staub

Chopin, Frédéric: Klavier-Konzert Nr.2 in f-moll

In der Reihe historischer Aufnahmen legt Audite eine Einspielung mit LeoMehr lesen

klassik.com | 26.12.2011 | Sophia Gustorff | December 26, 2011 | source: http://magazin.k... Mehr Glanz als Staub

Die Archiv-Archäologen machen immer wieder interessante Funde: Bei AuditeMehr lesen

Record Geijutsu | November 2011 | November 1, 2011

japanische Rezension siehe PDF!Mehr lesen

Classica | n° 137 novembre 2011 | Stéphane Friédérich | November 1, 2011

Voici un concert (4 juin 1950) particulièrement intéressant car ilMehr lesen

Audiophile Audition | September 18, 2011 | Gary Lemco | September 18, 2011 Two “neglected” masters--Julian von Karolyi and Leo Blech-- return in vivid colors for a concert of Chopin and Schubert from 1950, viscerally restored by Audite

Leo Blech (1871-1958) hardly endures as a famous name in the history ofMehr lesen

Classical Recordings Quarterly | 01.09.2011 | September 1, 2011

Another new release of great historical importance comes from Audite. This is dedicated to the German conductor Leo Blech (1871-1958) and theMehr lesen