Fricsay's orchestral work was characterised by a clear orchestral sound, the greatest possible musical energy and ceaseless formation of the music. His post-war career in Berlin began in 1948 with debuts at the Berlin Municipal Opera, the Radio Symphony Orchestra Berlin as well as with the Berlinmore

Ferenc Fricsay

"A valuable addition to his small discography is this Audite issue of live performances of Tchaikovsky's Symphony No. 5 with the Berlin Radio Symphony Orchestra, one of the most exciting you'll ever hear, coupled with Schumann's Piano Concerto in a live performance with the RIAS Orchestra and Alfred Cortot as soloist." (classicalcdreview.com)

Track List

Multimedia

- Ferenc Fricsay's speech on the occasion of the concert celebrating the 10th anniversary of the RSO Berlin, 24 Jan 1957

- 95498_Producer's Comment [german]_Tchaikovsky & Schumann

- Review of the Edition Ferenc Fricsay in Universitas

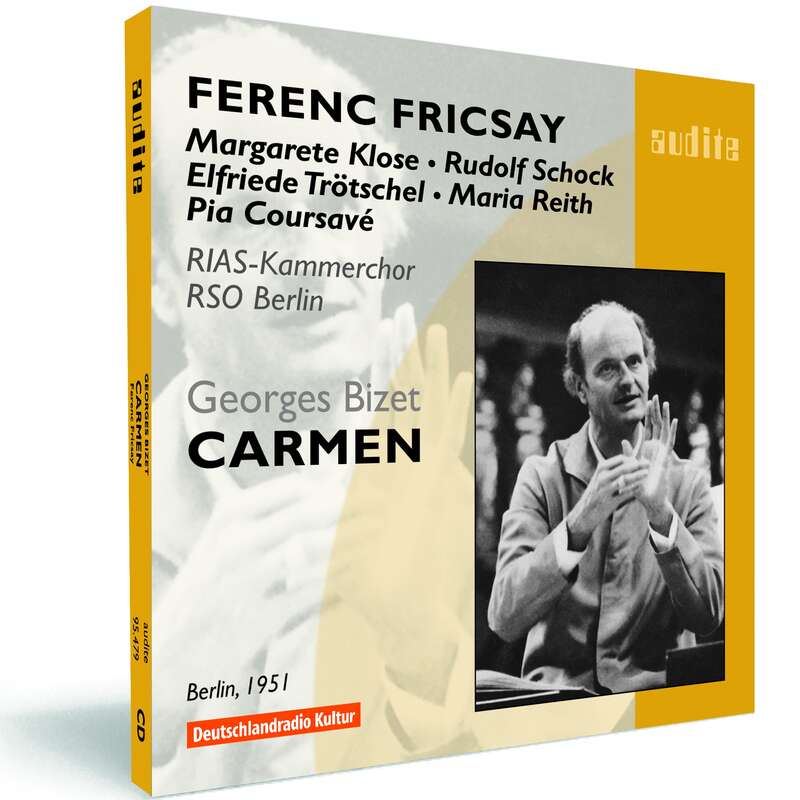

- 95497_Producer's Comment [german]_Bizet: Carmen

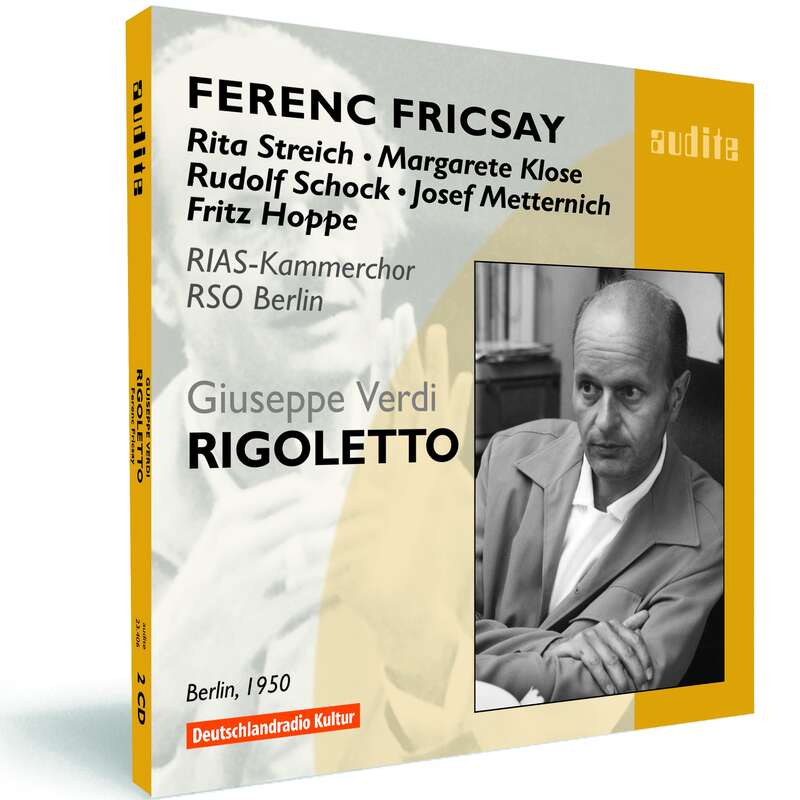

- 23406_Producer's Comment [deutsch]_Verdi: Rigoletto

- Producer's Comment [german]

- Review in Deutschlandradio Kultur, Radiofeuilleton on (25.06.2008)

- 23411_Producer's Comment [german]_Strauss: die Fledermaus

- 95593_Producer's Comment [german]_Beethoven

- 95596_Producer's Comment [german]_Mozart

- Supersonic Award for "Edition Ferenc Fricsay (VII)"

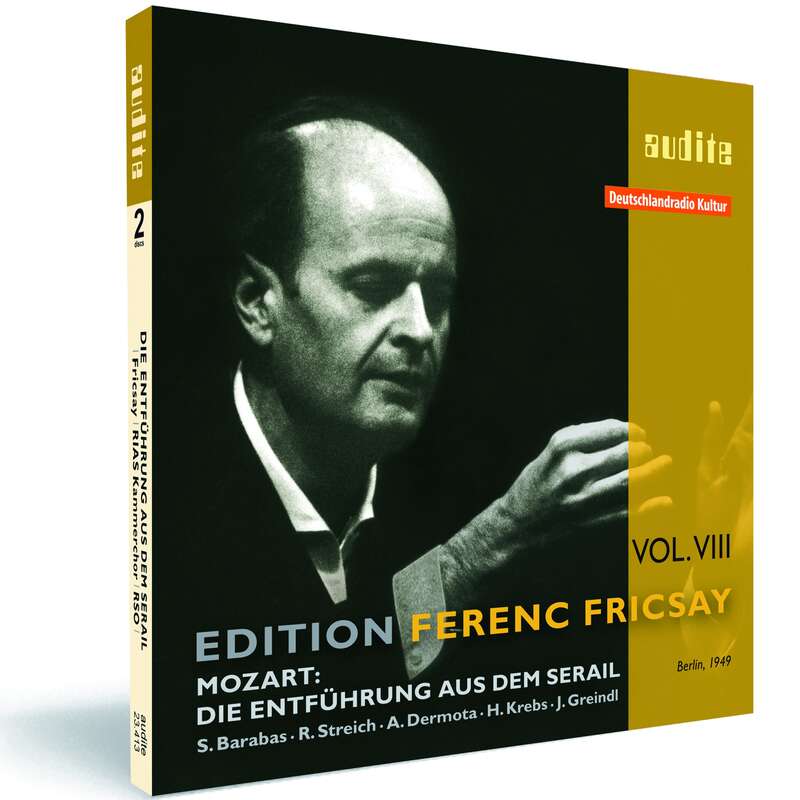

- Entführung aus dem Serail - audite audio trailer

- Supersonic Award for "Edition Ferenc Fricsay (VIII)"

- 23412_Producer's Comment [german]_Donizatti: Lucia di Lammermoor

- 95585_Producer's Comment [german]_Brahms

- Concert program of Rossini's Stabat Mater (Berlin, 1954)

- 95587_Producer's Comment [german]_Rossini: Stabat Mater

-

21407_Producer's Comment [german]_Ferenc Fricsay conducts Bartok

First-hand impressions of producer Ludger Böckenhoff [german]

- Press Info

- Supersonic Award_Pizzicato 042011

Informationen

Fricsay's orchestral work was characterised by a clear orchestral sound, the greatest possible musical energy and ceaseless formation of the music. His post-war career in Berlin began in 1948 with debuts at the Berlin Municipal Opera, the Radio Symphony Orchestra Berlin as well as with the Berlin Philharmonic and the RIAS Symphony Orchestra. Following his successful performances, Fricsay was appointed General Music Director of the Municipal Opera of Berlin in late 1948 taking effect until September 1949, and Principal Conductor of the RIAS Symphony Orchestra (later the Radio Symphony Orchestra Berlin; since 1993 Deutsches Symphonie-Orchester Berlin). From 1949 until 1954 Fricsay led the RIAS Symphony Orchestra, making his stamp on its performing culture and laying the cornerstone for open, contemporarily orientated programme planning. Fricsay played a central role in the reconstruction of musical life in post-war Germany, especially in Berlin. These activities are documented by this series, consisting of 14 parts so far, with archive recordings from the RIAS and the WDR from the early 1950s.

Reviews

Stereoplay | 09|2016 | Lothar Brandt | September 1, 2016 HighClass in HiRes

Fricsay ließ das RIAS-Sinfonieorchester 1950 bis 1952 immer wieder Strauss aufführen; einen repräsentativen Querschnitt der dabei entstandenen Aufnahmen hat audite zu einer wundervollen historischen CD zusammengefasst. Die berühmte Flusshuldigung „An der schönen blauen Donau“ walzt aus Berlin so authentisch, dass man sich nach Wien versetzt fühlt.Mehr lesen

ensuite Kulturmagazin | Mai 2016 | Francois Lilienfeld | May 1, 2016 Aufnahmen mit Ferenc Fricsay (2.Teil)

[…] Neben der Deutschen Grammophon gebührt auch der Firma audite ein großes Lob für ihre Bemühungen, Fricsay-Aufnahmen einem breiten Publikum zuMehr lesen

Audite 95.498 enthält zwei Konzertmitschnitte. Mit dem inzwischen in «Radio-Symphonie-Orchester Berlin» umbenannten RIAS-Orchester interpretiert Ferenc Fricsay Tschaikowskys Fünfte. Der Vergleich mit der DGG-Aufnahme von 1949 ist interessant: In beiden Aufführungen versteht es der Dirigent, die oft recht scharfen Kontraste zwischen Wildheit und lyrischen Stellen überzeugend darzubringen – und die Streicher des RIAS stehen den Berliner Philharmonikern in nichts nach: Beide Klangkörper sind grossartig. Die audite-Version ist jedoch besser durchdacht, konsequenter aufgebaut, insbesondere in den Mittelsätzen. Dies mag auch am Anlass liegen: Das Konzert vom 24. Januar 1957 fand zum zehnjährigen Jubiläum des Orchesters statt – ein besonders inspirierender Moment. Es ist schön, dass die CD auch die kurze Ansprache des Dirigenten enthält.

Mit dem anderen Dokument auf dieser Platte hat es eine besondere Bewandtnis: Es handelt sich um das Schumann-Klavierkonzert mit Alfred Cortot, 1951 mitgeschnitten. Eine brisante Geschichte, hatte doch Cortot während der deutschen Besatzung Frankreichs intensiv mit den Nazis und dem Vichy-Regime kollaboriert. Er nahm leitende Stellungen an und ignorierte zahlreiche Hilferufe bedrängter Künstler. Dies führte unter Anderem zum Bruch mit seinen früheren Trio-Kollegen und Freunden Jacques Thibaud und PabIo Casals. Doch etwas muss man ihm zugute halten (Das Folgende weiss ich dank den Memoiren von Casals): Im Gegensatz zu zahlreichen Kollegen, die sich mit Lügen und Rechtfertigungen durchschlängelten, oft sogar im Innersten Anhänger der Nazi-Ideologie blieben, zeigte Cortot Reue. Im Sommer 1945 besuchte er unangemeldet den großen Cellisten in Prades. «Es ist wahr, Pablo,» sagte er, «ich habe mit den Nazis gearbeitet, ich schäme mich, ich schäme mich furchtbar. Ich bin gekommen, um dich um Vergebung zu bitten.» So kann man denn die Tatsache, dass Cortot im Mai 1951 in Berlin spielte, auch als Geste der Versöhnung betrachten.

Soweit die zeitgeschichtlichen Hintergründe. Doch wie steht es mit der musikalischen Qualität? Da muss ich leider sagen, dass man diesen Mitschnitt besser hätte im Archiv schlummern lassen sollen. Auch ich bin kein Anhänger der Null-Fehler-Ästhetik (ein Ausdruck von Habakuk Traber im ausgezeichneten Beiheft). Zwei meiner Lieblingspianisten – Arthur Schnabel und Rudolf Serkin – passierten auch gelegentliche Schnitzer, aber eben: Sie geschahen gelegentlich und vermochten nicht, den gestalterischen Gestus zu stören. Bei Cortot jedoch hören wir regelmässig brutale Fehler, man hat dazu das Gefühl, dass Schumanns Partitur ihm gar nicht am Herzen liegt, so viele Willkürlichkeiten und Grobheiten erlaubt er sich.

Doch lassen sie sich nicht abhalten: Der Kauf der CD ist wegen der Tschaikowsky-Symphonie unbedingt empfehlenswert!

Auch in der audite-Serie finden wir Haydn- und Mozart-Symphonien. Leider sind es die gleichen, die schon bei DGG erschienen sind. Dies hängt wohl damit zusammen, dass Schallplattenaufnahmen oft im Anschluss an Radio-Produktionen stattfanden – und vergessen wir nicht, dass die Radio-Aufnahmen meist nicht zur Veröffentlichung bestimmt waren. Natürlich sind die Vergleiche interessant: Aber was gäben wir nicht dafür, statt zweimal KV 201 und KV 543 die «Linzer» und die «Prager» zu haben!

Bei den Haydn-Symphonien 44 und 98 spielt auf der audite Produktion zumindest ein anderes Orchester, nämlich das Kölner Rundfunk-Symphonie-Orchester. (audite 95.584)

Bei Mozart fällt die Unkonsequenz bei den Wiederholungen auf, die wohl oft mit der Sendezeit oder der Beschränkung einer Schallplattenseite zusammenhängt, wenn die Firma unbedingt eine ganze Symphonie auf eine Seite drängen wollte. In der A-dur-Symphonie KV 201 wiederholt Fricsay die Exposition des 1. Satzes bei DG, aber nicht bei audite. In der Es-dur-Symphonie KV 543 hält er es umgekehrt… Bei diesem Werk ist im Übrigen der Vergleich der beiden Fassungen des Trios im 3. Satz reizvoll: Hier die RIAS-Klarinetten mit ihrem samtweichen Ton, bei DG die Bläser der Wiener Symphoniker, die dem Wienerisch-Folkloristischen im Klang näher sind und etwas herber klingen. Die Qualität ist in beiden Fällen fabelhaft.

Die sehr kurze Exposition im g-moll-Werk wird immer wiederholt. (Symphonien Nrn 29, 39, 40: audite 95.596)

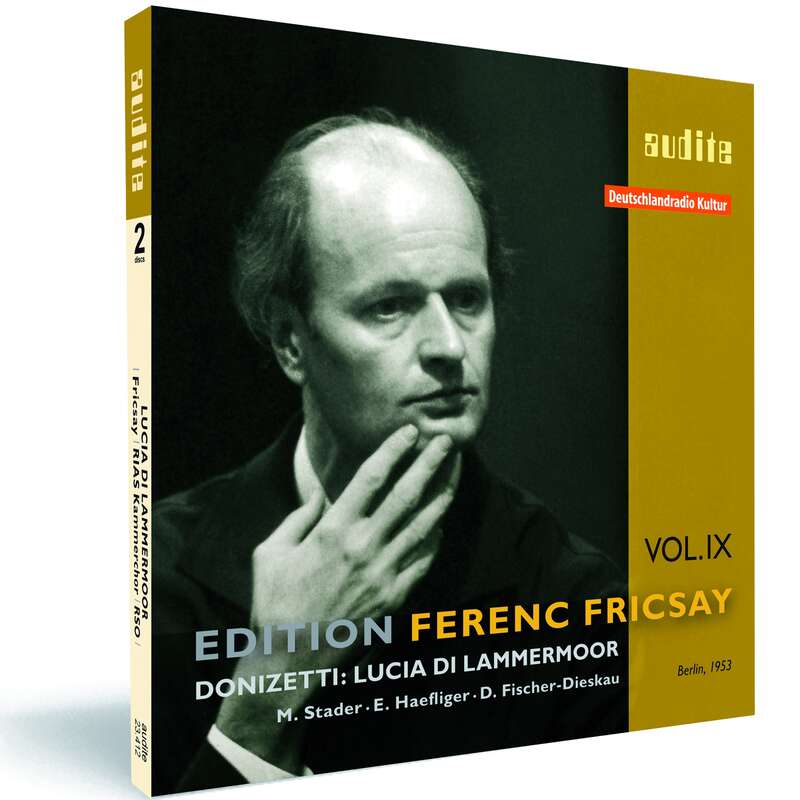

Eine absolute Sternstunde bietet audite mit der Einspielung von Donizettis «Lucia di Lammermoor» (audite 23.412). Diese Radio-Produktion von Januar 1954 wurde in deutscher Sprache aufgenommen, was damals eher der Normalfall war. Auch die vorgenommenen Kürzungen – 105 Minuten Spielzeit anstelle von gut anderthalb Stunden – entsprechen der Gewohnheit der Zeit; man musste noch lange auf komplette Aufführungen und Einspielungen warten. Dramaturgisch schwerwiegend ist vor allem das Fehlen der Begegnung zwischen Enrico und Edgardo am Anfang des dritten Aktes, wo sich die Gegenspieler zum Duell verabreden. Dadurch wirkt die letzte Szene – der Monolog Edgardos – nicht ganz folgerichtig. Dazu kommt das Problem, dass zwei gleich aufgebaute Szenen unmittelbar aufeinander folgen: erst Jubel, dann Umschwung ins Dramatisch-Tragische.

Auch die kurze Szene nach der Wahnsinnsarie, in der Enrico Reue zeigt, wäre für den dramatischen Ablauf wichtig: Ohne sie verschwindet diese Figur plötzlich im Nichts... Interessante Bemerkungen zu diesem Thema sind im Übrigen im ausgezeichneten Beiheft-Text von Habakuk Traber nachzulesen.

Doch, seien wir zufrieden mit dem, was wir haben: Denn die Aufführung ist schlicht und einfach überwältigend! Fricsay erweist sich einmal mehr als hochbegabter Dramatiker, RIAS-Orchester und -Chor (Einstudierung: Herbert Froitzheim) sind in Hochform. Zum Ereignis wird die Aufnahme jedoch durch Maria Staders Interpretation der Lucia. Gesangstechnisch und stimmlich kenne ich keine ebenbürtige Interpretin dieser Rolle, ausser Dame Joan Sutherland – und das ist aus meiner Feder ein Riesenkompliment! Maria Staders Porträt ist im Ansatz allerdings verschieden: Sie ist eine leidende Figur, eine Tragödin der leisen Töne. Den Wahnsinn stellt sie zurückhaltend, als Phantasma dar, nicht als dramatischen Gestus. Dass sie sich dabei genau an Donizetttis Notentext hält, ist ein weiterer Pluspunkt. Und der/die ungenannte Flötist(in) ergänzt den Gesang auf perfekte Weise. Ihr Partner, Ernst Haefliger, bewältigt die für ihn im Prinzip zu gewichtige Partie durch Intelligenz und perfektes technisches Können (ähnlich wie den Florestan im vor einem Monat besprochenen Fidelio). Wenn die beiden Künstler sich im Duett vereinigen, entsteht ein selten erreichter Wohlklang, ein perfektes Zusammengehen zweier zauberhaft schöner Stimmen; wahrlich, wir sind in der Welt des Belcanto!

Dietrich Fischer-Dieskaus Wutausbruch in der ersten Szene geschieht manchmal auf Kosten der Gesangslinie. Doch, ab dem Duett mit Lucia ist seine Interpretation des Enrico ein Modell an Gesang und Differenzierung. Auch die kürzeren Rollen sind sehr gut besetzt. Ein schottisches Sujet, von einem Italiener komponiert, auf deutsch aufgeführt: Wenn die Qualität stimmt, geht auch das!

Erwähnt sei noch, dass audite auf einer Doppel-CD die in der letzten Ensuite-Nummer hochgepriesene Aufnahme der «Fledermaus» als Einzelausgabe veröffentlicht hat (audite 23 411), mit einer hochinteressanten Dokumentation von Habakuk Traber im Beiheft.

ensuite Kulturmagazin | Mai 2016 | Francois Lilienfeld | May 1, 2016 Aufnahmen mit Ferenc Fricsay (2.Teil)

[…] Neben der Deutschen Grammophon gebührt auch der Firma audite ein großes Lob für ihre Bemühungen, Fricsay-Aufnahmen einem breiten Publikum zuMehr lesen

Audite 95.498 enthält zwei Konzertmitschnitte. Mit dem inzwischen in «Radio-Symphonie-Orchester Berlin» umbenannten RIAS-Orchester interpretiert Ferenc Fricsay Tschaikowskys Fünfte. Der Vergleich mit der DGG-Aufnahme von 1949 ist interessant: In beiden Aufführungen versteht es der Dirigent, die oft recht scharfen Kontraste zwischen Wildheit und lyrischen Stellen überzeugend darzubringen – und die Streicher des RIAS stehen den Berliner Philharmonikern in nichts nach: Beide Klangkörper sind grossartig. Die audite-Version ist jedoch besser durchdacht, konsequenter aufgebaut, insbesondere in den Mittelsätzen. Dies mag auch am Anlass liegen: Das Konzert vom 24. Januar 1957 fand zum zehnjährigen Jubiläum des Orchesters statt – ein besonders inspirierender Moment. Es ist schön, dass die CD auch die kurze Ansprache des Dirigenten enthält.

Mit dem anderen Dokument auf dieser Platte hat es eine besondere Bewandtnis: Es handelt sich um das Schumann-Klavierkonzert mit Alfred Cortot, 1951 mitgeschnitten. Eine brisante Geschichte, hatte doch Cortot während der deutschen Besatzung Frankreichs intensiv mit den Nazis und dem Vichy-Regime kollaboriert. Er nahm leitende Stellungen an und ignorierte zahlreiche Hilferufe bedrängter Künstler. Dies führte unter Anderem zum Bruch mit seinen früheren Trio-Kollegen und Freunden Jacques Thibaud und PabIo Casals. Doch etwas muss man ihm zugute halten (Das Folgende weiss ich dank den Memoiren von Casals): Im Gegensatz zu zahlreichen Kollegen, die sich mit Lügen und Rechtfertigungen durchschlängelten, oft sogar im Innersten Anhänger der Nazi-Ideologie blieben, zeigte Cortot Reue. Im Sommer 1945 besuchte er unangemeldet den großen Cellisten in Prades. «Es ist wahr, Pablo,» sagte er, «ich habe mit den Nazis gearbeitet, ich schäme mich, ich schäme mich furchtbar. Ich bin gekommen, um dich um Vergebung zu bitten.» So kann man denn die Tatsache, dass Cortot im Mai 1951 in Berlin spielte, auch als Geste der Versöhnung betrachten.

Soweit die zeitgeschichtlichen Hintergründe. Doch wie steht es mit der musikalischen Qualität? Da muss ich leider sagen, dass man diesen Mitschnitt besser hätte im Archiv schlummern lassen sollen. Auch ich bin kein Anhänger der Null-Fehler-Ästhetik (ein Ausdruck von Habakuk Traber im ausgezeichneten Beiheft). Zwei meiner Lieblingspianisten – Arthur Schnabel und Rudolf Serkin – passierten auch gelegentliche Schnitzer, aber eben: Sie geschahen gelegentlich und vermochten nicht, den gestalterischen Gestus zu stören. Bei Cortot jedoch hören wir regelmässig brutale Fehler, man hat dazu das Gefühl, dass Schumanns Partitur ihm gar nicht am Herzen liegt, so viele Willkürlichkeiten und Grobheiten erlaubt er sich.

Doch lassen sie sich nicht abhalten: Der Kauf der CD ist wegen der Tschaikowsky-Symphonie unbedingt empfehlenswert!

Auch in der audite-Serie finden wir Haydn- und Mozart-Symphonien. Leider sind es die gleichen, die schon bei DGG erschienen sind. Dies hängt wohl damit zusammen, dass Schallplattenaufnahmen oft im Anschluss an Radio-Produktionen stattfanden – und vergessen wir nicht, dass die Radio-Aufnahmen meist nicht zur Veröffentlichung bestimmt waren. Natürlich sind die Vergleiche interessant: Aber was gäben wir nicht dafür, statt zweimal KV 201 und KV 543 die «Linzer» und die «Prager» zu haben!

Bei den Haydn-Symphonien 44 und 98 spielt auf der audite Produktion zumindest ein anderes Orchester, nämlich das Kölner Rundfunk-Symphonie-Orchester. (audite 95.584)

Bei Mozart fällt die Unkonsequenz bei den Wiederholungen auf, die wohl oft mit der Sendezeit oder der Beschränkung einer Schallplattenseite zusammenhängt, wenn die Firma unbedingt eine ganze Symphonie auf eine Seite drängen wollte. In der A-dur-Symphonie KV 201 wiederholt Fricsay die Exposition des 1. Satzes bei DG, aber nicht bei audite. In der Es-dur-Symphonie KV 543 hält er es umgekehrt… Bei diesem Werk ist im Übrigen der Vergleich der beiden Fassungen des Trios im 3. Satz reizvoll: Hier die RIAS-Klarinetten mit ihrem samtweichen Ton, bei DG die Bläser der Wiener Symphoniker, die dem Wienerisch-Folkloristischen im Klang näher sind und etwas herber klingen. Die Qualität ist in beiden Fällen fabelhaft.

Die sehr kurze Exposition im g-moll-Werk wird immer wiederholt. (Symphonien Nrn 29, 39, 40: audite 95.596)

Eine absolute Sternstunde bietet audite mit der Einspielung von Donizettis «Lucia di Lammermoor» (audite 23.412). Diese Radio-Produktion von Januar 1954 wurde in deutscher Sprache aufgenommen, was damals eher der Normalfall war. Auch die vorgenommenen Kürzungen – 105 Minuten Spielzeit anstelle von gut anderthalb Stunden – entsprechen der Gewohnheit der Zeit; man musste noch lange auf komplette Aufführungen und Einspielungen warten. Dramaturgisch schwerwiegend ist vor allem das Fehlen der Begegnung zwischen Enrico und Edgardo am Anfang des dritten Aktes, wo sich die Gegenspieler zum Duell verabreden. Dadurch wirkt die letzte Szene – der Monolog Edgardos – nicht ganz folgerichtig. Dazu kommt das Problem, dass zwei gleich aufgebaute Szenen unmittelbar aufeinander folgen: erst Jubel, dann Umschwung ins Dramatisch-Tragische.

Auch die kurze Szene nach der Wahnsinnsarie, in der Enrico Reue zeigt, wäre für den dramatischen Ablauf wichtig: Ohne sie verschwindet diese Figur plötzlich im Nichts... Interessante Bemerkungen zu diesem Thema sind im Übrigen im ausgezeichneten Beiheft-Text von Habakuk Traber nachzulesen.

Doch, seien wir zufrieden mit dem, was wir haben: Denn die Aufführung ist schlicht und einfach überwältigend! Fricsay erweist sich einmal mehr als hochbegabter Dramatiker, RIAS-Orchester und -Chor (Einstudierung: Herbert Froitzheim) sind in Hochform. Zum Ereignis wird die Aufnahme jedoch durch Maria Staders Interpretation der Lucia. Gesangstechnisch und stimmlich kenne ich keine ebenbürtige Interpretin dieser Rolle, ausser Dame Joan Sutherland – und das ist aus meiner Feder ein Riesenkompliment! Maria Staders Porträt ist im Ansatz allerdings verschieden: Sie ist eine leidende Figur, eine Tragödin der leisen Töne. Den Wahnsinn stellt sie zurückhaltend, als Phantasma dar, nicht als dramatischen Gestus. Dass sie sich dabei genau an Donizetttis Notentext hält, ist ein weiterer Pluspunkt. Und der/die ungenannte Flötist(in) ergänzt den Gesang auf perfekte Weise. Ihr Partner, Ernst Haefliger, bewältigt die für ihn im Prinzip zu gewichtige Partie durch Intelligenz und perfektes technisches Können (ähnlich wie den Florestan im vor einem Monat besprochenen Fidelio). Wenn die beiden Künstler sich im Duett vereinigen, entsteht ein selten erreichter Wohlklang, ein perfektes Zusammengehen zweier zauberhaft schöner Stimmen; wahrlich, wir sind in der Welt des Belcanto!

Dietrich Fischer-Dieskaus Wutausbruch in der ersten Szene geschieht manchmal auf Kosten der Gesangslinie. Doch, ab dem Duett mit Lucia ist seine Interpretation des Enrico ein Modell an Gesang und Differenzierung. Auch die kürzeren Rollen sind sehr gut besetzt. Ein schottisches Sujet, von einem Italiener komponiert, auf deutsch aufgeführt: Wenn die Qualität stimmt, geht auch das!

Erwähnt sei noch, dass audite auf einer Doppel-CD die in der letzten Ensuite-Nummer hochgepriesene Aufnahme der «Fledermaus» als Einzelausgabe veröffentlicht hat (audite 23 411), mit einer hochinteressanten Dokumentation von Habakuk Traber im Beiheft.

ensuite Kulturmagazin | Mai 2016 | Francois Lilienfeld | May 1, 2016 Aufnahmen mit Ferenc Fricsay (2.Teil)

[…] Neben der Deutschen Grammophon gebührt auch der Firma audite ein großes Lob für ihre Bemühungen, Fricsay-Aufnahmen einem breiten Publikum zuMehr lesen

Audite 95.498 enthält zwei Konzertmitschnitte. Mit dem inzwischen in «Radio-Symphonie-Orchester Berlin» umbenannten RIAS-Orchester interpretiert Ferenc Fricsay Tschaikowskys Fünfte. Der Vergleich mit der DGG-Aufnahme von 1949 ist interessant: In beiden Aufführungen versteht es der Dirigent, die oft recht scharfen Kontraste zwischen Wildheit und lyrischen Stellen überzeugend darzubringen – und die Streicher des RIAS stehen den Berliner Philharmonikern in nichts nach: Beide Klangkörper sind grossartig. Die audite-Version ist jedoch besser durchdacht, konsequenter aufgebaut, insbesondere in den Mittelsätzen. Dies mag auch am Anlass liegen: Das Konzert vom 24. Januar 1957 fand zum zehnjährigen Jubiläum des Orchesters statt – ein besonders inspirierender Moment. Es ist schön, dass die CD auch die kurze Ansprache des Dirigenten enthält.

Mit dem anderen Dokument auf dieser Platte hat es eine besondere Bewandtnis: Es handelt sich um das Schumann-Klavierkonzert mit Alfred Cortot, 1951 mitgeschnitten. Eine brisante Geschichte, hatte doch Cortot während der deutschen Besatzung Frankreichs intensiv mit den Nazis und dem Vichy-Regime kollaboriert. Er nahm leitende Stellungen an und ignorierte zahlreiche Hilferufe bedrängter Künstler. Dies führte unter Anderem zum Bruch mit seinen früheren Trio-Kollegen und Freunden Jacques Thibaud und PabIo Casals. Doch etwas muss man ihm zugute halten (Das Folgende weiss ich dank den Memoiren von Casals): Im Gegensatz zu zahlreichen Kollegen, die sich mit Lügen und Rechtfertigungen durchschlängelten, oft sogar im Innersten Anhänger der Nazi-Ideologie blieben, zeigte Cortot Reue. Im Sommer 1945 besuchte er unangemeldet den großen Cellisten in Prades. «Es ist wahr, Pablo,» sagte er, «ich habe mit den Nazis gearbeitet, ich schäme mich, ich schäme mich furchtbar. Ich bin gekommen, um dich um Vergebung zu bitten.» So kann man denn die Tatsache, dass Cortot im Mai 1951 in Berlin spielte, auch als Geste der Versöhnung betrachten.

Soweit die zeitgeschichtlichen Hintergründe. Doch wie steht es mit der musikalischen Qualität? Da muss ich leider sagen, dass man diesen Mitschnitt besser hätte im Archiv schlummern lassen sollen. Auch ich bin kein Anhänger der Null-Fehler-Ästhetik (ein Ausdruck von Habakuk Traber im ausgezeichneten Beiheft). Zwei meiner Lieblingspianisten – Arthur Schnabel und Rudolf Serkin – passierten auch gelegentliche Schnitzer, aber eben: Sie geschahen gelegentlich und vermochten nicht, den gestalterischen Gestus zu stören. Bei Cortot jedoch hören wir regelmässig brutale Fehler, man hat dazu das Gefühl, dass Schumanns Partitur ihm gar nicht am Herzen liegt, so viele Willkürlichkeiten und Grobheiten erlaubt er sich.

Doch lassen sie sich nicht abhalten: Der Kauf der CD ist wegen der Tschaikowsky-Symphonie unbedingt empfehlenswert!

Auch in der audite-Serie finden wir Haydn- und Mozart-Symphonien. Leider sind es die gleichen, die schon bei DGG erschienen sind. Dies hängt wohl damit zusammen, dass Schallplattenaufnahmen oft im Anschluss an Radio-Produktionen stattfanden – und vergessen wir nicht, dass die Radio-Aufnahmen meist nicht zur Veröffentlichung bestimmt waren. Natürlich sind die Vergleiche interessant: Aber was gäben wir nicht dafür, statt zweimal KV 201 und KV 543 die «Linzer» und die «Prager» zu haben!

Bei den Haydn-Symphonien 44 und 98 spielt auf der audite Produktion zumindest ein anderes Orchester, nämlich das Kölner Rundfunk-Symphonie-Orchester. (audite 95.584)

Bei Mozart fällt die Unkonsequenz bei den Wiederholungen auf, die wohl oft mit der Sendezeit oder der Beschränkung einer Schallplattenseite zusammenhängt, wenn die Firma unbedingt eine ganze Symphonie auf eine Seite drängen wollte. In der A-dur-Symphonie KV 201 wiederholt Fricsay die Exposition des 1. Satzes bei DG, aber nicht bei audite. In der Es-dur-Symphonie KV 543 hält er es umgekehrt… Bei diesem Werk ist im Übrigen der Vergleich der beiden Fassungen des Trios im 3. Satz reizvoll: Hier die RIAS-Klarinetten mit ihrem samtweichen Ton, bei DG die Bläser der Wiener Symphoniker, die dem Wienerisch-Folkloristischen im Klang näher sind und etwas herber klingen. Die Qualität ist in beiden Fällen fabelhaft.

Die sehr kurze Exposition im g-moll-Werk wird immer wiederholt. (Symphonien Nrn 29, 39, 40: audite 95.596)

Eine absolute Sternstunde bietet audite mit der Einspielung von Donizettis «Lucia di Lammermoor» (audite 23.412). Diese Radio-Produktion von Januar 1954 wurde in deutscher Sprache aufgenommen, was damals eher der Normalfall war. Auch die vorgenommenen Kürzungen – 105 Minuten Spielzeit anstelle von gut anderthalb Stunden – entsprechen der Gewohnheit der Zeit; man musste noch lange auf komplette Aufführungen und Einspielungen warten. Dramaturgisch schwerwiegend ist vor allem das Fehlen der Begegnung zwischen Enrico und Edgardo am Anfang des dritten Aktes, wo sich die Gegenspieler zum Duell verabreden. Dadurch wirkt die letzte Szene – der Monolog Edgardos – nicht ganz folgerichtig. Dazu kommt das Problem, dass zwei gleich aufgebaute Szenen unmittelbar aufeinander folgen: erst Jubel, dann Umschwung ins Dramatisch-Tragische.

Auch die kurze Szene nach der Wahnsinnsarie, in der Enrico Reue zeigt, wäre für den dramatischen Ablauf wichtig: Ohne sie verschwindet diese Figur plötzlich im Nichts... Interessante Bemerkungen zu diesem Thema sind im Übrigen im ausgezeichneten Beiheft-Text von Habakuk Traber nachzulesen.

Doch, seien wir zufrieden mit dem, was wir haben: Denn die Aufführung ist schlicht und einfach überwältigend! Fricsay erweist sich einmal mehr als hochbegabter Dramatiker, RIAS-Orchester und -Chor (Einstudierung: Herbert Froitzheim) sind in Hochform. Zum Ereignis wird die Aufnahme jedoch durch Maria Staders Interpretation der Lucia. Gesangstechnisch und stimmlich kenne ich keine ebenbürtige Interpretin dieser Rolle, ausser Dame Joan Sutherland – und das ist aus meiner Feder ein Riesenkompliment! Maria Staders Porträt ist im Ansatz allerdings verschieden: Sie ist eine leidende Figur, eine Tragödin der leisen Töne. Den Wahnsinn stellt sie zurückhaltend, als Phantasma dar, nicht als dramatischen Gestus. Dass sie sich dabei genau an Donizetttis Notentext hält, ist ein weiterer Pluspunkt. Und der/die ungenannte Flötist(in) ergänzt den Gesang auf perfekte Weise. Ihr Partner, Ernst Haefliger, bewältigt die für ihn im Prinzip zu gewichtige Partie durch Intelligenz und perfektes technisches Können (ähnlich wie den Florestan im vor einem Monat besprochenen Fidelio). Wenn die beiden Künstler sich im Duett vereinigen, entsteht ein selten erreichter Wohlklang, ein perfektes Zusammengehen zweier zauberhaft schöner Stimmen; wahrlich, wir sind in der Welt des Belcanto!

Dietrich Fischer-Dieskaus Wutausbruch in der ersten Szene geschieht manchmal auf Kosten der Gesangslinie. Doch, ab dem Duett mit Lucia ist seine Interpretation des Enrico ein Modell an Gesang und Differenzierung. Auch die kürzeren Rollen sind sehr gut besetzt. Ein schottisches Sujet, von einem Italiener komponiert, auf deutsch aufgeführt: Wenn die Qualität stimmt, geht auch das!

Erwähnt sei noch, dass audite auf einer Doppel-CD die in der letzten Ensuite-Nummer hochgepriesene Aufnahme der «Fledermaus» als Einzelausgabe veröffentlicht hat (audite 23 411), mit einer hochinteressanten Dokumentation von Habakuk Traber im Beiheft.

ensuite Kulturmagazin | Mai 2016 | Francois Lilienfeld | May 1, 2016 Aufnahmen mit Ferenc Fricsay (2.Teil)

[…] Neben der Deutschen Grammophon gebührt auch der Firma audite ein großes Lob für ihre Bemühungen, Fricsay-Aufnahmen einem breiten Publikum zuMehr lesen

Audite 95.498 enthält zwei Konzertmitschnitte. Mit dem inzwischen in «Radio-Symphonie-Orchester Berlin» umbenannten RIAS-Orchester interpretiert Ferenc Fricsay Tschaikowskys Fünfte. Der Vergleich mit der DGG-Aufnahme von 1949 ist interessant: In beiden Aufführungen versteht es der Dirigent, die oft recht scharfen Kontraste zwischen Wildheit und lyrischen Stellen überzeugend darzubringen – und die Streicher des RIAS stehen den Berliner Philharmonikern in nichts nach: Beide Klangkörper sind grossartig. Die audite-Version ist jedoch besser durchdacht, konsequenter aufgebaut, insbesondere in den Mittelsätzen. Dies mag auch am Anlass liegen: Das Konzert vom 24. Januar 1957 fand zum zehnjährigen Jubiläum des Orchesters statt – ein besonders inspirierender Moment. Es ist schön, dass die CD auch die kurze Ansprache des Dirigenten enthält.

Mit dem anderen Dokument auf dieser Platte hat es eine besondere Bewandtnis: Es handelt sich um das Schumann-Klavierkonzert mit Alfred Cortot, 1951 mitgeschnitten. Eine brisante Geschichte, hatte doch Cortot während der deutschen Besatzung Frankreichs intensiv mit den Nazis und dem Vichy-Regime kollaboriert. Er nahm leitende Stellungen an und ignorierte zahlreiche Hilferufe bedrängter Künstler. Dies führte unter Anderem zum Bruch mit seinen früheren Trio-Kollegen und Freunden Jacques Thibaud und PabIo Casals. Doch etwas muss man ihm zugute halten (Das Folgende weiss ich dank den Memoiren von Casals): Im Gegensatz zu zahlreichen Kollegen, die sich mit Lügen und Rechtfertigungen durchschlängelten, oft sogar im Innersten Anhänger der Nazi-Ideologie blieben, zeigte Cortot Reue. Im Sommer 1945 besuchte er unangemeldet den großen Cellisten in Prades. «Es ist wahr, Pablo,» sagte er, «ich habe mit den Nazis gearbeitet, ich schäme mich, ich schäme mich furchtbar. Ich bin gekommen, um dich um Vergebung zu bitten.» So kann man denn die Tatsache, dass Cortot im Mai 1951 in Berlin spielte, auch als Geste der Versöhnung betrachten.

Soweit die zeitgeschichtlichen Hintergründe. Doch wie steht es mit der musikalischen Qualität? Da muss ich leider sagen, dass man diesen Mitschnitt besser hätte im Archiv schlummern lassen sollen. Auch ich bin kein Anhänger der Null-Fehler-Ästhetik (ein Ausdruck von Habakuk Traber im ausgezeichneten Beiheft). Zwei meiner Lieblingspianisten – Arthur Schnabel und Rudolf Serkin – passierten auch gelegentliche Schnitzer, aber eben: Sie geschahen gelegentlich und vermochten nicht, den gestalterischen Gestus zu stören. Bei Cortot jedoch hören wir regelmässig brutale Fehler, man hat dazu das Gefühl, dass Schumanns Partitur ihm gar nicht am Herzen liegt, so viele Willkürlichkeiten und Grobheiten erlaubt er sich.

Doch lassen sie sich nicht abhalten: Der Kauf der CD ist wegen der Tschaikowsky-Symphonie unbedingt empfehlenswert!

Auch in der audite-Serie finden wir Haydn- und Mozart-Symphonien. Leider sind es die gleichen, die schon bei DGG erschienen sind. Dies hängt wohl damit zusammen, dass Schallplattenaufnahmen oft im Anschluss an Radio-Produktionen stattfanden – und vergessen wir nicht, dass die Radio-Aufnahmen meist nicht zur Veröffentlichung bestimmt waren. Natürlich sind die Vergleiche interessant: Aber was gäben wir nicht dafür, statt zweimal KV 201 und KV 543 die «Linzer» und die «Prager» zu haben!

Bei den Haydn-Symphonien 44 und 98 spielt auf der audite Produktion zumindest ein anderes Orchester, nämlich das Kölner Rundfunk-Symphonie-Orchester. (audite 95.584)

Bei Mozart fällt die Unkonsequenz bei den Wiederholungen auf, die wohl oft mit der Sendezeit oder der Beschränkung einer Schallplattenseite zusammenhängt, wenn die Firma unbedingt eine ganze Symphonie auf eine Seite drängen wollte. In der A-dur-Symphonie KV 201 wiederholt Fricsay die Exposition des 1. Satzes bei DG, aber nicht bei audite. In der Es-dur-Symphonie KV 543 hält er es umgekehrt… Bei diesem Werk ist im Übrigen der Vergleich der beiden Fassungen des Trios im 3. Satz reizvoll: Hier die RIAS-Klarinetten mit ihrem samtweichen Ton, bei DG die Bläser der Wiener Symphoniker, die dem Wienerisch-Folkloristischen im Klang näher sind und etwas herber klingen. Die Qualität ist in beiden Fällen fabelhaft.

Die sehr kurze Exposition im g-moll-Werk wird immer wiederholt. (Symphonien Nrn 29, 39, 40: audite 95.596)

Eine absolute Sternstunde bietet audite mit der Einspielung von Donizettis «Lucia di Lammermoor» (audite 23.412). Diese Radio-Produktion von Januar 1954 wurde in deutscher Sprache aufgenommen, was damals eher der Normalfall war. Auch die vorgenommenen Kürzungen – 105 Minuten Spielzeit anstelle von gut anderthalb Stunden – entsprechen der Gewohnheit der Zeit; man musste noch lange auf komplette Aufführungen und Einspielungen warten. Dramaturgisch schwerwiegend ist vor allem das Fehlen der Begegnung zwischen Enrico und Edgardo am Anfang des dritten Aktes, wo sich die Gegenspieler zum Duell verabreden. Dadurch wirkt die letzte Szene – der Monolog Edgardos – nicht ganz folgerichtig. Dazu kommt das Problem, dass zwei gleich aufgebaute Szenen unmittelbar aufeinander folgen: erst Jubel, dann Umschwung ins Dramatisch-Tragische.

Auch die kurze Szene nach der Wahnsinnsarie, in der Enrico Reue zeigt, wäre für den dramatischen Ablauf wichtig: Ohne sie verschwindet diese Figur plötzlich im Nichts... Interessante Bemerkungen zu diesem Thema sind im Übrigen im ausgezeichneten Beiheft-Text von Habakuk Traber nachzulesen.

Doch, seien wir zufrieden mit dem, was wir haben: Denn die Aufführung ist schlicht und einfach überwältigend! Fricsay erweist sich einmal mehr als hochbegabter Dramatiker, RIAS-Orchester und -Chor (Einstudierung: Herbert Froitzheim) sind in Hochform. Zum Ereignis wird die Aufnahme jedoch durch Maria Staders Interpretation der Lucia. Gesangstechnisch und stimmlich kenne ich keine ebenbürtige Interpretin dieser Rolle, ausser Dame Joan Sutherland – und das ist aus meiner Feder ein Riesenkompliment! Maria Staders Porträt ist im Ansatz allerdings verschieden: Sie ist eine leidende Figur, eine Tragödin der leisen Töne. Den Wahnsinn stellt sie zurückhaltend, als Phantasma dar, nicht als dramatischen Gestus. Dass sie sich dabei genau an Donizetttis Notentext hält, ist ein weiterer Pluspunkt. Und der/die ungenannte Flötist(in) ergänzt den Gesang auf perfekte Weise. Ihr Partner, Ernst Haefliger, bewältigt die für ihn im Prinzip zu gewichtige Partie durch Intelligenz und perfektes technisches Können (ähnlich wie den Florestan im vor einem Monat besprochenen Fidelio). Wenn die beiden Künstler sich im Duett vereinigen, entsteht ein selten erreichter Wohlklang, ein perfektes Zusammengehen zweier zauberhaft schöner Stimmen; wahrlich, wir sind in der Welt des Belcanto!

Dietrich Fischer-Dieskaus Wutausbruch in der ersten Szene geschieht manchmal auf Kosten der Gesangslinie. Doch, ab dem Duett mit Lucia ist seine Interpretation des Enrico ein Modell an Gesang und Differenzierung. Auch die kürzeren Rollen sind sehr gut besetzt. Ein schottisches Sujet, von einem Italiener komponiert, auf deutsch aufgeführt: Wenn die Qualität stimmt, geht auch das!

Erwähnt sei noch, dass audite auf einer Doppel-CD die in der letzten Ensuite-Nummer hochgepriesene Aufnahme der «Fledermaus» als Einzelausgabe veröffentlicht hat (audite 23 411), mit einer hochinteressanten Dokumentation von Habakuk Traber im Beiheft.

ensuite Kulturmagazin | Mai 2016 | Francois Lilienfeld | May 1, 2016 Aufnahmen mit Ferenc Fricsay (2.Teil)

[…] Neben der Deutschen Grammophon gebührt auch der Firma audite ein großes Lob für ihre Bemühungen, Fricsay-Aufnahmen einem breiten Publikum zuMehr lesen

Audite 95.498 enthält zwei Konzertmitschnitte. Mit dem inzwischen in «Radio-Symphonie-Orchester Berlin» umbenannten RIAS-Orchester interpretiert Ferenc Fricsay Tschaikowskys Fünfte. Der Vergleich mit der DGG-Aufnahme von 1949 ist interessant: In beiden Aufführungen versteht es der Dirigent, die oft recht scharfen Kontraste zwischen Wildheit und lyrischen Stellen überzeugend darzubringen – und die Streicher des RIAS stehen den Berliner Philharmonikern in nichts nach: Beide Klangkörper sind grossartig. Die audite-Version ist jedoch besser durchdacht, konsequenter aufgebaut, insbesondere in den Mittelsätzen. Dies mag auch am Anlass liegen: Das Konzert vom 24. Januar 1957 fand zum zehnjährigen Jubiläum des Orchesters statt – ein besonders inspirierender Moment. Es ist schön, dass die CD auch die kurze Ansprache des Dirigenten enthält.

Mit dem anderen Dokument auf dieser Platte hat es eine besondere Bewandtnis: Es handelt sich um das Schumann-Klavierkonzert mit Alfred Cortot, 1951 mitgeschnitten. Eine brisante Geschichte, hatte doch Cortot während der deutschen Besatzung Frankreichs intensiv mit den Nazis und dem Vichy-Regime kollaboriert. Er nahm leitende Stellungen an und ignorierte zahlreiche Hilferufe bedrängter Künstler. Dies führte unter Anderem zum Bruch mit seinen früheren Trio-Kollegen und Freunden Jacques Thibaud und PabIo Casals. Doch etwas muss man ihm zugute halten (Das Folgende weiss ich dank den Memoiren von Casals): Im Gegensatz zu zahlreichen Kollegen, die sich mit Lügen und Rechtfertigungen durchschlängelten, oft sogar im Innersten Anhänger der Nazi-Ideologie blieben, zeigte Cortot Reue. Im Sommer 1945 besuchte er unangemeldet den großen Cellisten in Prades. «Es ist wahr, Pablo,» sagte er, «ich habe mit den Nazis gearbeitet, ich schäme mich, ich schäme mich furchtbar. Ich bin gekommen, um dich um Vergebung zu bitten.» So kann man denn die Tatsache, dass Cortot im Mai 1951 in Berlin spielte, auch als Geste der Versöhnung betrachten.

Soweit die zeitgeschichtlichen Hintergründe. Doch wie steht es mit der musikalischen Qualität? Da muss ich leider sagen, dass man diesen Mitschnitt besser hätte im Archiv schlummern lassen sollen. Auch ich bin kein Anhänger der Null-Fehler-Ästhetik (ein Ausdruck von Habakuk Traber im ausgezeichneten Beiheft). Zwei meiner Lieblingspianisten – Arthur Schnabel und Rudolf Serkin – passierten auch gelegentliche Schnitzer, aber eben: Sie geschahen gelegentlich und vermochten nicht, den gestalterischen Gestus zu stören. Bei Cortot jedoch hören wir regelmässig brutale Fehler, man hat dazu das Gefühl, dass Schumanns Partitur ihm gar nicht am Herzen liegt, so viele Willkürlichkeiten und Grobheiten erlaubt er sich.

Doch lassen sie sich nicht abhalten: Der Kauf der CD ist wegen der Tschaikowsky-Symphonie unbedingt empfehlenswert!

Auch in der audite-Serie finden wir Haydn- und Mozart-Symphonien. Leider sind es die gleichen, die schon bei DGG erschienen sind. Dies hängt wohl damit zusammen, dass Schallplattenaufnahmen oft im Anschluss an Radio-Produktionen stattfanden – und vergessen wir nicht, dass die Radio-Aufnahmen meist nicht zur Veröffentlichung bestimmt waren. Natürlich sind die Vergleiche interessant: Aber was gäben wir nicht dafür, statt zweimal KV 201 und KV 543 die «Linzer» und die «Prager» zu haben!

Bei den Haydn-Symphonien 44 und 98 spielt auf der audite Produktion zumindest ein anderes Orchester, nämlich das Kölner Rundfunk-Symphonie-Orchester. (audite 95.584)

Bei Mozart fällt die Unkonsequenz bei den Wiederholungen auf, die wohl oft mit der Sendezeit oder der Beschränkung einer Schallplattenseite zusammenhängt, wenn die Firma unbedingt eine ganze Symphonie auf eine Seite drängen wollte. In der A-dur-Symphonie KV 201 wiederholt Fricsay die Exposition des 1. Satzes bei DG, aber nicht bei audite. In der Es-dur-Symphonie KV 543 hält er es umgekehrt… Bei diesem Werk ist im Übrigen der Vergleich der beiden Fassungen des Trios im 3. Satz reizvoll: Hier die RIAS-Klarinetten mit ihrem samtweichen Ton, bei DG die Bläser der Wiener Symphoniker, die dem Wienerisch-Folkloristischen im Klang näher sind und etwas herber klingen. Die Qualität ist in beiden Fällen fabelhaft.

Die sehr kurze Exposition im g-moll-Werk wird immer wiederholt. (Symphonien Nrn 29, 39, 40: audite 95.596)

Eine absolute Sternstunde bietet audite mit der Einspielung von Donizettis «Lucia di Lammermoor» (audite 23.412). Diese Radio-Produktion von Januar 1954 wurde in deutscher Sprache aufgenommen, was damals eher der Normalfall war. Auch die vorgenommenen Kürzungen – 105 Minuten Spielzeit anstelle von gut anderthalb Stunden – entsprechen der Gewohnheit der Zeit; man musste noch lange auf komplette Aufführungen und Einspielungen warten. Dramaturgisch schwerwiegend ist vor allem das Fehlen der Begegnung zwischen Enrico und Edgardo am Anfang des dritten Aktes, wo sich die Gegenspieler zum Duell verabreden. Dadurch wirkt die letzte Szene – der Monolog Edgardos – nicht ganz folgerichtig. Dazu kommt das Problem, dass zwei gleich aufgebaute Szenen unmittelbar aufeinander folgen: erst Jubel, dann Umschwung ins Dramatisch-Tragische.

Auch die kurze Szene nach der Wahnsinnsarie, in der Enrico Reue zeigt, wäre für den dramatischen Ablauf wichtig: Ohne sie verschwindet diese Figur plötzlich im Nichts... Interessante Bemerkungen zu diesem Thema sind im Übrigen im ausgezeichneten Beiheft-Text von Habakuk Traber nachzulesen.

Doch, seien wir zufrieden mit dem, was wir haben: Denn die Aufführung ist schlicht und einfach überwältigend! Fricsay erweist sich einmal mehr als hochbegabter Dramatiker, RIAS-Orchester und -Chor (Einstudierung: Herbert Froitzheim) sind in Hochform. Zum Ereignis wird die Aufnahme jedoch durch Maria Staders Interpretation der Lucia. Gesangstechnisch und stimmlich kenne ich keine ebenbürtige Interpretin dieser Rolle, ausser Dame Joan Sutherland – und das ist aus meiner Feder ein Riesenkompliment! Maria Staders Porträt ist im Ansatz allerdings verschieden: Sie ist eine leidende Figur, eine Tragödin der leisen Töne. Den Wahnsinn stellt sie zurückhaltend, als Phantasma dar, nicht als dramatischen Gestus. Dass sie sich dabei genau an Donizetttis Notentext hält, ist ein weiterer Pluspunkt. Und der/die ungenannte Flötist(in) ergänzt den Gesang auf perfekte Weise. Ihr Partner, Ernst Haefliger, bewältigt die für ihn im Prinzip zu gewichtige Partie durch Intelligenz und perfektes technisches Können (ähnlich wie den Florestan im vor einem Monat besprochenen Fidelio). Wenn die beiden Künstler sich im Duett vereinigen, entsteht ein selten erreichter Wohlklang, ein perfektes Zusammengehen zweier zauberhaft schöner Stimmen; wahrlich, wir sind in der Welt des Belcanto!

Dietrich Fischer-Dieskaus Wutausbruch in der ersten Szene geschieht manchmal auf Kosten der Gesangslinie. Doch, ab dem Duett mit Lucia ist seine Interpretation des Enrico ein Modell an Gesang und Differenzierung. Auch die kürzeren Rollen sind sehr gut besetzt. Ein schottisches Sujet, von einem Italiener komponiert, auf deutsch aufgeführt: Wenn die Qualität stimmt, geht auch das!

Erwähnt sei noch, dass audite auf einer Doppel-CD die in der letzten Ensuite-Nummer hochgepriesene Aufnahme der «Fledermaus» als Einzelausgabe veröffentlicht hat (audite 23 411), mit einer hochinteressanten Dokumentation von Habakuk Traber im Beiheft.

Die Tonkunst | Juli 2013 | Tobias Pfleger | July 1, 2013 Edition Ferenc Fricsay – Werke von Haydn, Mozart, Beethoven, Rossini, Bizet, Brahms, Strauß, Verdi, Bartók u. a.

Ferenc Fricsay gehörte zu den bedeutenden Dirigenten des mittleren 20.Mehr lesen

Die Tonkunst | Juli 2013 | Tobias Pfleger | July 1, 2013 Edition Ferenc Fricsay – Werke von Haydn, Mozart, Beethoven, Rossini, Bizet, Brahms, Strauß, Verdi, Bartók u. a.

Ferenc Fricsay gehörte zu den bedeutenden Dirigenten des mittleren 20.Mehr lesen

Die Tonkunst | Juli 2013 | Tobias Pfleger | July 1, 2013 Edition Ferenc Fricsay – Werke von Haydn, Mozart, Beethoven, Rossini, Bizet, Brahms, Strauß, Verdi, Bartók u. a.

Ferenc Fricsay gehörte zu den bedeutenden Dirigenten des mittleren 20.Mehr lesen

Die Tonkunst | Juli 2013 | Tobias Pfleger | July 1, 2013 Edition Ferenc Fricsay – Werke von Haydn, Mozart, Beethoven, Rossini, Bizet, Brahms, Strauß, Verdi, Bartók u. a.

Ferenc Fricsay gehörte zu den bedeutenden Dirigenten des mittleren 20.Mehr lesen

Die Tonkunst | Juli 2013 | Tobias Pfleger | July 1, 2013 Edition Ferenc Fricsay – Werke von Haydn, Mozart, Beethoven, Rossini, Bizet, Brahms, Strauß, Verdi, Bartók u. a.

Ferenc Fricsay gehörte zu den bedeutenden Dirigenten des mittleren 20.Mehr lesen

Die Tonkunst | Juli 2013 | Tobias Pfleger | July 1, 2013 Edition Ferenc Fricsay – Werke von Haydn, Mozart, Beethoven, Rossini, Bizet, Brahms, Strauß, Verdi, Bartók u. a.

Ferenc Fricsay gehörte zu den bedeutenden Dirigenten des mittleren 20.Mehr lesen

Die Tonkunst | Juli 2013 | Tobias Pfleger | July 1, 2013 Edition Ferenc Fricsay – Werke von Haydn, Mozart, Beethoven, Rossini, Bizet, Brahms, Strauß, Verdi, Bartók u. a.

Die Klangtechnik ist für damalige Verhältnisse von sehr hoher Qualität, der helle, fast metallische Charakter des fokussierten Streicherklangs unterstützt Fricsays Ästhetik klanglicher Transparenz und Tiefenschärfe.<br /> [...] In paradigmatischer Weise zeigt sich Fricsays zündende Verbindung von flexibler Begleitung, Sog der Kantilene, rhythmischem Feuer, geschärfter Artikulation und suggestiver Phrasierung in den Opern- und Operettenaufnahmen; sie bilden weitere Höhepunkte der Edition.Mehr lesen

[...] In paradigmatischer Weise zeigt sich Fricsays zündende Verbindung von flexibler Begleitung, Sog der Kantilene, rhythmischem Feuer, geschärfter Artikulation und suggestiver Phrasierung in den Opern- und Operettenaufnahmen; sie bilden weitere Höhepunkte der Edition.

Die Tonkunst | Juli 2013 | Tobias Pfleger | July 1, 2013 Edition Ferenc Fricsay – Werke von Haydn, Mozart, Beethoven, Rossini, Bizet, Brahms, Strauß, Verdi, Bartók u. a.

Ferenc Fricsay gehörte zu den bedeutenden Dirigenten des mittleren 20.Mehr lesen

Die Tonkunst | Juli 2013 | Tobias Pfleger | July 1, 2013 Edition Ferenc Fricsay – Werke von Haydn, Mozart, Beethoven, Rossini, Bizet, Brahms, Strauß, Verdi, Bartók u. a.

Ferenc Fricsay gehörte zu den bedeutenden Dirigenten des mittleren 20.Mehr lesen

Die Tonkunst | Juli 2013 | Tobias Pfleger | July 1, 2013 Edition Ferenc Fricsay – Werke von Haydn, Mozart, Beethoven, Rossini, Bizet, Brahms, Strauß, Verdi, Bartók u. a.

Ferenc Fricsay gehörte zu den bedeutenden Dirigenten des mittleren 20.Mehr lesen

Die Tonkunst | Juli 2013 | Tobias Pfleger | July 1, 2013 Edition Ferenc Fricsay – Werke von Haydn, Mozart, Beethoven, Rossini, Bizet, Brahms, Strauß, Verdi, Bartók u. a.

Ferenc Fricsay gehörte zu den bedeutenden Dirigenten des mittleren 20.Mehr lesen

Die Tonkunst | Juli 2013 | Tobias Pfleger | July 1, 2013 Edition Ferenc Fricsay – Werke von Haydn, Mozart, Beethoven, Rossini, Bizet, Brahms, Strauß, Verdi, Bartók u. a.

Ferenc Fricsay gehörte zu den bedeutenden Dirigenten des mittleren 20.Mehr lesen

Die Tonkunst | Juli 2013 | Tobias Pfleger | July 1, 2013 Edition Ferenc Fricsay – Werke von Haydn, Mozart, Beethoven, Rossini, Bizet, Brahms, Strauß, Verdi, Bartók u. a.

Ferenc Fricsay gehörte zu den bedeutenden Dirigenten des mittleren 20.Mehr lesen

Die Tonkunst | Juli 2013 | Tobias Pfleger | July 1, 2013 Edition Ferenc Fricsay – Werke von Haydn, Mozart, Beethoven, Rossini, Bizet, Brahms, Strauß, Verdi, Bartók u. a.

Ferenc Fricsay gehörte zu den bedeutenden Dirigenten des mittleren 20.Mehr lesen

American Record Guide | 16.10.2012 | David Radcliffe | October 16, 2012

The 1950s was the great decade for Bartok performances — would that the composer had been still alive! It was a remarkable recovery considering theMehr lesen

The RIAS Symphony doesn’t help: they are competent in what must have been unfamiliar repertoire, but they certainly come across as Berliners: their sound is smooth and attractive but lacking in earth tones. That said, Fricsay’s soloists, Hungarian compatriots all, supply the necessary ingredients to make Bartok sing.

The concertos are all wonderful, particularly Tibor Varga in the violin concerto and Geza Anda in the Third Piano Concerto. Conceding that Bartok performances can work even in the mode of high-modernist abstraction, I much prefer the color and inflection that typified central European music-making in the composer’s lifetime. Since Bartok concertos are not heard so often now as in the 1950s, and since this collection has been admirably produced from original sources (studio and broadcast) it is well worth seeking out.

WDR 3 | Freitag, 20.07.2012: Klassik Forum | Hans Winking | July 20, 2012

Historische Aufnahmen

Ferenc Fricsay dirigiert Werke von Béla Bartók

In Berlin nach dem 2. Weltkrieg wuchs mit dem 1946 gegründetenMehr lesen

Pizzicato | N° 221 - 3/2012 | March 1, 2012 ICMA 2012: Historical Recording

Pizzicato: Supersonic – Fricsay hat Bartok nie weichgekocht, er serviert ihn uns in intensiv aufbereitetem rohen Zustand, mit viel Impetus und einerMehr lesen

DeutschlandRadio | 01.02.2012 | February 1, 2012

International Classical Music Award 2012 für historische Aufnahmen aus dem RIAS-Archiv

"Ferenc Fricsay conducts Béla Bartók • The Complete RIAS Recordings" ausgezeichnet

Die Edition "Ferenc Fricsay conducts Béla Bartók • The Complete RIAS Recordings" aus den Archiven des Deutschlandradios erhält den InternationalMehr lesen

Die vorliegende Anthologie der Bartók-Aufnahmen Ferenc Fricsays für den RIAS Berlin dokumentiert ein Gipfeltreffen berühmter ungarischer Solisten: die Pianisten Géza Anda, Andor Foldes, Louis Kentner und der Geiger Tibor Varga. Fricsays bewährter und kongenialer Gesangssolist ist Dietrich Fischer-Dieskau. Der Dirigent Ferenc Fricsay gilt als authentischer Interpret der Werke Béla Bartóks, was dem Wert der Einspielungen zusätzliches Gewicht verleiht. In der klanglichen Präsentation überzeugt die Edition durch äußerst sorgfältiges Remastering der originalen Masterbänder.

Nach zahlreichen anderen Auszeichnungen, etwa dem "Preis der deutschen Schallplattenkritik" 2/2011 gewinnt die Edition "Ferenc Fricsay conducts Béla Bartók" mit dem International Classical Music Award (ICMA), dem Nachfolger des MIDEM Classical Award, nun eine der höchsten internationalen Auszeichnungen der Musikszene. Die Classical Awards werden jährlich von einer unabhängigen Jury vergeben, der Musikjournalisten führender internationaler Musikmagazine, Radiosender und Musikinstitutionen angehören.

Die Preisverleihung findet am 15. Mai 2012 in Nantes statt.

Fono Forum | Dezember 2011 | Christoph Vratz | December 1, 2011 Empfehlungen unserer Mitarbeiter 2011

Historische Aufnahme des Jahres:<br /> <br /> Die Wiederentdeckungen beim Label Audite (etwa Ferenc Fricsay mit Bartók)Mehr lesen

Die Wiederentdeckungen beim Label Audite (etwa Ferenc Fricsay mit Bartók)

Die Wiederentdeckungen beim Label Audite (etwa Ferenc Fricsay mit Bartók)

www.opusklassiek.nl | december 2011 | Aart van der Wal | December 1, 2011

In het Berlijnse Titania-Palast (in mijn oren min of meer een akoestischMehr lesen

Hi-Fi News

| October 2011 | Christopher Breunig | October 1, 2011

Radio revelations

All Fricsays’ 1960s Bartók recordings made by RIAS engineers have been collected as an Audite set. In some ways they surpass the DG studio equivalents. Christopher Breunig explains why

Few music premieres have created such uproar as Le Sacre du printemps, given in Paris in 1913 under Pierre Monteux. Nowadays the score presents fewMehr lesen

Look back 40 years to the 1961 Gramophone catalogue and there’s a substantial Bartók listing: six versions of the relatively popular Concerto for Orchestra, for instance – though none far better than the 1948 Decca 78rpm set by van Beinum. One name that recurs is that of the Hungarian conductor, signed to DG, Ferenc Fricsay. He was in charge of the RIAS Orchestra (Radio in American Sector, Berlin), with access to the Berlin Philharmonic for certain projects. Sessions were held in the Jesus-Christus-Kirche, which had excellent acoustics. The classical director of the orchestra Elsa Schiller invited Fricsay to Berlin in 1948; later she would become a key figure in organising Deutsche Grammophon’s postwar repertory.

The German company Audite has now issued a 3CD set [21.407] from radio tapes duplicating most of the DG material but with different soloists, eg. Foldes in the Rhapsody; Kentner in the Third Piano Concerto [live]. A 1953 studio Second with Géza Anda adds to his live versions with Karajan, Boulez, et al. There’s no Concerto for Orchestra or First Piano Concerto, but Audite offers alternatives for the Second Violin Concerto (Tibor Varga) [live]. Cantata profana (Fischer-Dieskau/Krebs), Dance Suite, Divertimento for strings [live], Two portraits (Rudolf Schulz) and Music for strings, percussion and celesta.

These RIAS recordings were also made in the Berlin church; the live tapes are from the Titania-Palast. The booklet note veers from dry facts to contentious opinion!

Some tape!

We all know that, as Allied bombers were flying over Germany, radio engineers were still tinkering with stereo and were able to record on wire (precursor to tape). The tape quality on DG mono LPs has always amazed me and in this Audite set there’s a prime example with the Third Piano Concerto. The levels were set, frankly, far too high and with the soloist rather close. But even when the overload is obvious, somehow it still sounds ‘musical’.

This is the performance which stands out for me as most significant. Louis Kentner, born in Hungary (as Lajos), had come to the UK in 1935, marrying into the Menuhin family, and had, with the BBC SO under Boult, given the European premiere of this work – they recorded it the very next day, in February 1946.

A Liszt specialist, he plays here with total aplomb, notably in the counterpoint of the finale. The ‘night music’ section of the Adagio religioso, instead of bristling with insects and eery rustles, sounds more akin to a Beethoven scherzando. His touch put me in mind of something the composer had demonstrated to Andor Foldes: ‘This [playing one note on the piano] is sound; this [making an interval] is music.’ The last two notes of movements (ii) and (iii) here are very much musical statements. Notwithstanding the limitations of the 1950 source, many orchestral colours struck me anew. In sum: this may not be a version to introduce a listener to the concerto, but it’s a version those familar with it should on no account miss. And it illustrates perfectly the thesis that today’s smoother readings lose something indefinable yet essential.

Brilliant illumination

Fricsay died aged only 49. If you don’t know his musicianship, the intensity in the slow movement of the Divertimento here (far greater than on his DG version) will surely be a revelation. He appeared, said Menuhin, ‘like a comet on the horizon … no-one had greater talent.’

Scherzo | Jg. XXVI, N° 269 | Santiago Martín Bermúdez | August 1, 2011 Bartók y Fricsay: Históricos

Las grabaciones de obras de Bartók dirigidas por Ferenc Fricsay en laMehr lesen

www.operanews.com | July 2011 — Vol. 76, No. 1 | David Shengold | July 1, 2011 Bartók: Cantata Profana (and other instrumental works)

Ferenc Fricsay (1914–63) was a master of many musical styles but broughtMehr lesen

Fanfare | Issue 34:6 (July/Aug 2011) | Lynn René Bayley | July 1, 2011

This wonderful three-CD set presents itself as Fricsay’s complete recordings of Bartók’s music, yet the liner notes refer to DG studio recordingsMehr lesen

What is present is, for the most part, marvelous, though the tightly miked, over-bright sound of the Violin Concerto No. 2 and the Divertimento for String Orchestra somewhat spoil the effect of the music. In both, the brass and high strings sound as shrill as the worst NBC Symphony broadcasts, and this shrill sound also affects Varga’s otherwise excellent solo playing. On sonic rather than musical terms, I was glad when they were over. The remastering engineer should have softened the sound with a judicious reduction of treble and possibly the addition of a small amount of reverb.

Needless to say, the studio recordings are all magnificent, not only sonically but meeting Fricsay’s high standards for musical phrasing. I’m convinced that it is only because the famous Fritz Reiner recording is in stereo that his performance of the Music for Strings, etc. is touted so highly; musically Fricsay makes several points in the music that Reiner does not. The liner notes lament that the Cantata profana is sung in German in order to accommodate two of Fricsay’s favorite singers, Helmut Krebs and Dietrich Fischer-Dieskau. No matter, for the performance itself is splendid and, sonics again aside, it has never been surpassed.

In a review I previously wrote of a modern pianist’s recordings of the Bartók concertos, I brought up the Annie Fischer–Igor Markevitch recording of No. 3 as an example of what the music really should sound like. The Anda–Fricsay recording of No. 2 is yet another example. The music flies like the wind, none of the brass interjections or rhythmic propulsion are ignored, yet none of it sounds like a jackhammer chopping up the pavement of your brain. Indeed, the Adagio enters and maintains a particularly soft and mysterious sound world that is the essence of Bartók’s post-Romanticism. The notes take Kentner to task for glossing over “some of the intricacies of the fragile dialogue between soloist and orchestra in the middle movement” of the Third Concerto, but I find this a small if noticeable blemish in this live concert performance. Many of the orchestral textures completely contradict what one hears in the modern recording on Chandos, and even Kentner’s very masculine reading has more of a legato feeling.

If you take in stride some of the harshness in the live performances (particularly the violin concerto), you’ll definitely want this set in your collection. So much in these performances represents Bartók’s music as it should sound, and it should be remembered that Kodály, Bartók, and Dohnányi were Fricsay’s teachers at the Liszt Music Academy in Budapest. Historically informed performance students, take heed.

Classical Recordings Quarterly | Summer 2011 | Alan Sanders | July 1, 2011

This set contains all the surviving RIAS recordings by Ferenc Fricsay of Bartók's music (a 1958 recording of Bluebeards Castle was woefullyMehr lesen

Though the radio recordings of the remaining works all date from 1950-53 they are all more than adequate in sound – sometimes they are startlingly good. Varga's live recording of the Second Violin Concerto is the only failure in Audite's set. The soloist's playing is frankly very poor, since it is technically fallible, with bad intonation and an unpleasantly insistent, rapid vibrato, and as recorded Vargas tone quality is squally and scratchy. (In their "Portrait" issue DG offered Varga's commercial recording, made some months earlier. Here the playing is more accurate, but the unpleasant vibrato and undernourished tone are again in evidence.) It is a relief to hear Rudolf Schulz's solo violin performance in the First Portrait, for he plays most beautifully.

Music for Strings, Percussion and Celesta, with its separate instrumental groups, does really need stereo recording, but Fricsay's lithe, intense performance is superlative. In common with the Violin Concerto the Divertimento performance derives from a concert performance, rather than one prepared in the radio studio. Fricsay uses a big string group and neither intonation nor ensemble are accurate, but the performance is characterful – strong, poetic and full of energy. In the Dance Suite Fricsay, as opposed to Dorati in his equally authoritative but very different performances, is more flexible, less insistent rhythmically, and his tempi tend to be a bit faster. Two equally valid views of this appealing work.

Audite's third disc comprises works for piano and orchestra played by three pianists famous for their Bartók. Andor Foldes is given a forward balance in the Rhapsody, but not even his advocacy can convince me that this early, derivative work is an important item in the composer's output. Géza Anda's commercial stereo recording of the Second Concerto with Fricsay is familiar to Bartók admirers. In his 1953 performance the younger Anda chooses quite fast tempi in the outer movements, but Fricsay follows willingly, and the result is a fine combination of virtuoso playing and conducting. Both the poetic sections of the middle movement and its quicksilver elements come to life vividly. It's good to have such an important souvenir of Kentner's Bartók in the Third Concerto. He brings a satisfyingly tougher than usual approach to the work as a whole – nothing is 'prettified', and his performance and that of the orchestra are quite brilliant.

Junge Freiheit | Nr. 26/11 (24. Juni 2011) | Sebastian Hennig | June 24, 2011 Behutsame Formbildung

Die Aufnahmen von Béla Bartóks Orchesterwerken durch dasMehr lesen

www.ResMusica.com | 20 juin 2011 | Pierre-Jean Tribot | June 20, 2011 Fricsay dirige Bartók, un monument d’Histoire

L’excellent label berlinois Audite réputé pour le grand soin apportéMehr lesen

Schwäbische Zeitung | Freitag, 10. Juni 2011 | man | June 10, 2011 The Hungarian Connection

Das Label Audite veröffentlicht die interessanten und impulsivenMehr lesen

Der Reinbeker | Jg. 47, Nr. 11 (6. Juni 2011) | Peter Steder | June 6, 2011 Von Klassik bis Jazz und Rock

Ein Knüller: Erstveröffentlichung aller erhaltenen Bartok-EinspielungenMehr lesen

www.schallplattenkritik.de | 2-2011 | Christoph Zimmermann | May 15, 2011 Historische Aufnahmen Klassik

Schatzgrube RIAS: Fricsays hochemotionales, energisches Dirigat läßtMehr lesen

www.schallplattenkritik.de | 2/2011 | Prof. Dr. Lothar Prox | May 15, 2011

Urkunde siehe PDFMehr lesen

www.klavier.de

| 08.05.2011 | Tobias Pfleger | May 8, 2011

Scharfe Rhythmen

Bartok, Bela: Violinkonzert Nr.2

Ferenc Fricsays Einsatz für die Musik Béla Bartóks wird von Audite mitMehr lesen

klassik.com | 08.05.2011 | Tobias Pfleger | May 8, 2011 | source: http://magazin.k... Scharfe Rhythmen

Das Label Audite hat sich in der Vergangenheit mit der VeröffentlichungMehr lesen

Diapason | N° 591 Mai 2011 | Patrick Szersnovicz | May 1, 2011 Bela Bartok

«Dans une partition, je m'attaque d'abord au passage le plus faible et c'est à partir de là que je donne forme à l'ensemble», disait FerencMehr lesen

Tout aussi électrisante, et bénéficiant d'une étonnante clarté des attaques, est la Musique pour cordes, percussion et célesta captée le 14 octobre 1952, au minutage plus généreux que la version de juin 1953 (DG). Inspiré de bout en bout, Fricsay souligne chaque incise tout en privilégiant la continuité, l'ampleur de respiration, l'airain des rythmes et un éclairage polyphonique d'une extrême sensibilité. Vertus précieuses dans la Suite de danses captée le 10 juin 1953 comme dans le Divertimento pour cordes (live du 11 février 1952).

Un rien distant, Fricsay souligne moins les inflexions «hungarisantes» du Concerto pour violon n° 2 (avec Tibor Varga, 1951) que lors de l'enregistrement avec les Berliner Philharmoniker (DG, 1951), tandis que les qualités poétiques et analytiques de la version «officielle» du Concerto pour piano n° 2 avec Geza Anda (DG ou Philips, 1959) ne sont pas tout à fait égalées. Andor Foldes dans la Rhapsodie pour piano et orchestre (studio, 12 décembre 1951) et plus encore Louis Kentner dans le Concerto n° 3 (live, 16 janvier 1950) semblent en revanche aller plus loin dans la simplicité lumineuse. Inégal, donc. Mais à ce niveau, et avec une telle qualité sonore: indispensable!

Fono Forum | Mai 2011 | Thomas Schulz | May 1, 2011 Authentisch

Man darf wohl ohne Übertreibung feststellen, dass kein Dirigent unmittelbar nach dem Zweiten Weltkrieg so viel für die Akzeptanz der Musik BélaMehr lesen

Was zuallererst überrascht, ist die hervorragende Klangqualität. Den CDs liegen die originalen Rundfunkbänder zugrunde, und durch das Remastering wurde eine Transparenz erreicht, die vorbildlich genannt werden kann; eine Ausnahme bildet lediglich der Live-Mitschnitt des dritten Klavierkonzerts. Weniger überraschen dürfte das durchweg hervorragende interpretatorische Niveau; Fricsay, der noch bei Bartók studierte, beherrscht naturgemäß das spezifisch ungarische Element dieser Musik, ihr gleichsam der Sprachmelodie abgelauschtes Rubato. Auch weigert er sich, Bartóks Musik im Tonfall eines permanenten "barbaro" ihrer zahlreichen Facetten zu berauben.

Adäquat unterstützt wird er dabei von den Solisten: Andor Foldes in der Rhapsodie op. 1, Géza Anda im zweiten und Louis Kentner im dritten Klavierkonzert sowie Tibor Varga im Violinkonzert Nr. 2. Die "Cantata profana" erklingt in einer deutschen Übersetzung, doch Dietrich Fischer-Dieskau und dem Tenor Helmut Krebs gelingt es, Inhalt und Grundaussage des viel zu selten aufgeführten Werks überzeugend zu transportieren.

Stereo | 5/2011 Mai | Thomas Schulz | May 1, 2011

Béla Bartók

Orchesterwerke und Konzerte

Kein Dirigent unmittelbar nach dem Zweiten Weltkrieg hat wohl so viel fürMehr lesen

Classica | n° 132 mai 2011 | Stéphane Friédérich | May 1, 2011

Quand Fricsay dirige Bartók

LE LABEL ALLEMAND AUDITE ÉDITE UNE ANTHOLOGIE BARTÓK DU LEGS DE FRICSAY AVEC LE RIAS DE BERLIN. IDIOMATIQUE ET MAGNIFIQUE!

Le label Audite a réuni dans ce coffret de 3 CD une anthologie Bartók (etMehr lesen

auditorium | May 2011 | May 1, 2011

koreanische Rezension siehe PDF!Mehr lesen

Gramophone | May 2011 | Rob Cowan | May 1, 2011

Rob Cowan's monthly survey of reissues and archive recordings

Musical evangelists – A trio of releases that re-energise familiar repertoire

Audite continues its valuable series of radio broadcasts of that most gifted of regenerative post-war conductors, Ferenc Fricsay, with a three-disc,Mehr lesen

Louis Kentner gave the Third Concerto's European premiere and his big-boned version of the Third calls for plenty of Lisztian thunder, especially in the outer movements, whereas the central Adagio religioso recalls the free-flowing style of Bartók's own piano-playing. Fricsay's commercial record of the Second Violin Concerto with Tibor Varga was always highly regarded, even though not everyone takes to Varga's fast and rather unvarying vibrato. Although undeniably exciting, this 1951 live performance falls prey to some ragged tuttis while Varga himself bows one or two conspicuously rough phrases. To be honest, I much preferred the warmer, less nervy playing of violinist Rudolf Schulz in the first of the Two Portraits, while the wild waltz-time Second Portrait (a bitter distortion of the First's dewy-eyed love theme) is taken at just the right tempo. Fricsay's 1952 live version of the Divertimento for strings passes on the expected fierce attack in favour of something more expressively legato (certainly in the opening Allegro non troppo) and parts of the Dance Suite positively ooze sensuality, especially for the opening of the finale, which sounds like some evil, stealthy predator creeping towards its prey at dead of night. Fricsay's versions of the Music for Strings, Percussion and Celesta and Cantata profana (with Helmut Krebs and Dietrich Fischer-Dieskau, sung in German) combine an appreciation of Bartók's mystical side with a keenly focused approach to the faster music's syncopated rhythms. Both works were recorded by Fricsay commercially but the extra adrenalin rush – and, in the case of Strings, Percussion and Celesta, extra breadth of utterance – in these radio versions provides their own justification. Good mono sound throughout and excellent notes by Wolfgang Rathert.

I was very pleased to see that Pristine Classical has reissued Albert Sammons's vital and musically persuasive 1926 account of Beethoven's Kreutzer Sonata, a performance that pre-dates the great Huberman-Friedman version and that, in some key respects, is almost its equal. Regarding Sammon's pianist, the Australian William Murdoch, the critic William James Turner wrote (in 1916), "even when we get to the best pianists it is rarely, if ever, that we find a combination of exceptional technical mastery with tone-power, delicacy of touch, brilliance, command of colour, sensitiveness of phrasing, variety of feeling, imagination and vital passion. Mr Murdoch possesses all these qualities to a high degree."

Pristine's coupling is a real curio and, at first glance, something of a find – Sammons in 1937 playing Fauré's First Sonata, a work which, so far as I know, is not otherwise represented in his discography and that suits his refined brand of emotionalism. But, alas, there is a significant drawback in the piano-playing of Edie Miller, which is ham-fisted to a fault and in one or two places technically well below par, not exactly what you want for the fragile world of Fauré's pianowriting. But if you can blank out the pianist from your listening, it's worth trying for Sammons's wonderful contribution alone. Otherwise, stick to the Beethoven.

A quite different style of Beethoven interpretation arrives via Andromeda in the form of a complete symphony cycle given live in Vienna in 1960 by the Philharmonia Orchestra under Otto Klemperer with, in the Choral Symphony, the Wiener Singverein and soloists Wilma Lipp, Ursula Boese, Fritz Wunderlich and Franz Crass (who delivers a sonorous, warmly felt bass recitative). Inevitable comparisons with Klemperer's roughly contemporaneous EMI cycle reveal some quicker tempi live (ie, in the Eroica's Marcia funebre), an occasionally sweeter turn of phrase among the strings (the opening of the Pastoral's second movement) and a more forthright presence overall, although beware some ragged ensemble and a mono balance that turns Klemperer's normally helpful decision to divide his violin desks into a bit of a liability, meaning that the Seconds are more distant than the Firsts.

Turn to the commercial recordings and stereo balancing maximises on Klemperer's clarity-conscious orchestral layout and the balance is superb, although common to both is the fairly forward placing of the woodwinds. Still, an interesting set, one to place beside Andromeda's recently released Beethoven cycle, the one shared between London (Royal Philharmonic) and Vienna (State Opera Orchestra) under the volatile baton of Hermann Scherchen (Andromeda ANDRCD9078, on five CDs and published last year). If Klemperer invariably fulfilled one's expectations, Scherchen usually confounded them.

Die Rheinpfalz | Nr.90 (Samstag, 16. April 2011) | pom | April 16, 2011 Bartok: Orchester-Werke mit Ferenc Fricsay

Bartoks Musik ist ebenso universal, geschrieben von einem Kosmopoliten, wieMehr lesen

thewholenote.com | April 2011 | Bruce Surtees | April 1, 2011 Old Wine In New Bottles – Fine Old Recordings

The deservedly honoured Hungarian conductor Ferenc Fricsay (1914-1973) ledMehr lesen

Pizzicato | N° 212 - 4/2011 | Rémy Franck | April 1, 2011 Fricsays Bartók

Bela Bartóks Musik ist eng mit der Volksmusik seiner Heimat verbunden, eine Konstante in einem Schaffen, das sich stilistisch im Laufe der JahreMehr lesen

Die vorliegende Zusammenstellung aus den Jahren 1950-53 umfasst alle im RIAS-Archiv erhaltenen Bartók-Einspielungen Fricsays. Sie runden ein Bild ab, das man von Fricsays DG-Aufnahmen aus dieser Zeit hatte.

Fricsay hat Bartók nie weichgekocht, er serviert ihn uns in intensiv aufbereitetem rohen Zustand, mit viel Impetus und einer aufregenden Mischung aus Zynismus, Ironie, Resignation und leidenschaftlicher Beseeltheit. Ein Leckerbissen ist gleich das 2. Violinkonzert mit Tibor Varga. Das schnelle Vibrato des Geigers mag heute ungewohnt klingen, aber der schmachtend lyrische langsame Satz und die virtuosen Ecksätze sind doch sehr interessant. Die beiden 'Portraits', das erste packend emotional, das zweite fulminant virtuos, sind weitere Höhepunkte, genau wie die aufregende Interpretation der Musik für Saiteninstrumente, Schlagzeug und Celesta, mit einem sehr trotzigen 2. Satz, der auf eine düstere Einleitung folgt, und einem notturnohaften, mysteriösen 3. Satz mit Nightmare-Charakter.

Die wenig aufgeführte Cantata profana (Untertitel: Die Zauberhirsche) ist ein Vokalwerk für Tenor, Bariton, Chor und Orchester aus dem Jahre 1930. Ein rumänisches Volkslied mit der Geschichte eines Vaters und seiner neun Söhne, die auf die Jagd gehen, einen Hirsch zu schießen und dabei selbst in Hirsche verwandelt werden, bildet die Vorlage für das Werk. Sie wird hier in einer packenden Interpretation vorgelegt.

Sehr konzentrierte Einspielungen gibt es vom Klavierkonzert Nr. 2 mit Geza Anda sowie von der Klavierrhapsodie mit Andor Foldes.

Record Geijutsu | APR. 2011 | April 1, 2011 Bartók

japanische Rezension siehe PDFMehr lesen

Audiophile Audition | March 29, 2011 | Gary Lemco | March 29, 2011 A splendid assemblage of conductor Ferenc Fricsay’s homage to Bartok, a project to inscribe an integral Bartok legacy but frustrated by the conductor’s untimely demise

The powerful affinity between Hungarian conductor Ferenc FricsayMehr lesen

Die Zeit | N° 12 (17. März 2011) | Wolfram Goertz | March 17, 2011

Der Durchleuchter

So enthusiastisch dirigierte Ferenc Fricsay Musik von Béla Bartók

Er war in Wien angekommen und trotzdem unglücklich. Er dirigierte an derMehr lesen

Classical Recordings Quarterly | Spring 2011 | Norbert Hornig | March 1, 2011 continental report

The Audite label is very busy in releasing new remastered tapes from German broadcast companies, and has enlarged its discography of the greatMehr lesen

Another release from Audite is very special: a live recording of Stravinsky's rarely performed Persephone (a melodrama in three parts for reciter, vocal soloist, double chorus and orchestra). Stravinsky composed Perséphone in 1933-34. The performance on Audite took place in 1960 at the Frankfurt Funkhaus, and the tape is from the archives of the Hessischer Rundfunk (Hessian Radio). Dean Dixon conducts the Symphony Orchestra of the Hessischer Rundfunk and, quite sensationally, Fritz Wunderlich sings the tenor role, for only one time in his life. So this live recording is a collector's item for all Wunderlich fans. The actress Doris Schade was perfectly cast as Perséphone (CD 95.619).

Rheinische Post | Freitag, 25. Februar 2011 | Wolfram Goertz | February 25, 2011 Ferenc Fricsay dirigiert Musik von Bela Bartók

Wenn es über eine Platte heißt, sie sei eine "editorisch sehr mutige Leitung", dann wird man bisweilen mit einem Langweiler konfrontiert, der auchMehr lesen

Ferenc Fricsay war einer der großen Dirigenten des 20. Jahrhunderts, vom Publikum verehrt, von den Musikern geliebt und gefürchtet. Fricsay empfand sich als Durchleuchter, er äderte Musiker hell und klar, statt Linien feucht zu bepinseln. Seinem Landsmann Bela Bartók war er besonders verbunden, und dessen Musik nahm auch eine wichtige Stellung in den Aufnahmen ein, die Fricsay in den frühen Fünfzigern mit dem Rias-Orchester machte. Er waren Einspielungen fürs Archiv des jungen Senders, aber Fricsay geizte mit Temperament nie.

Die Box bietet Klavier- und Violinkonzerte (mit Geza Anda, Andor Foldes und Tibor Varga), die Musik für Saiteninstrumente, Schlagzeug und Celesta, die oft unterschätzte Cantata profana (mit Helmut Krebs und Dietrich Fischer-Dieskau) und das hinreißende Divertimento für Streichorchester. Über allem schwebt und feuert unverkennbar Fricsays Enthusiasmus.

Südwest Presse

| Donnerstag, 24. Februar 2011 | Jürgen Kanold | February 24, 2011

Bevorzugt spätromantisch

Ungarn unter sich

Ungarischer Dirigent führt mit ungarischen Solisten das Werk desMehr lesen

Schwäbisches Tagblatt

| 24.02.2011 | SWP | February 24, 2011

Bevorzugt spätromantisch

Aufnahmen mit Diana Damrau und Hilary Hahn

Ungarischer Dirigent führt mit ungarischen Solisten das Werk desMehr lesen

Der neue Merker | Donnerstag, 24.02.2011 | February 24, 2011 Ferenc Fricsay conducts Béla Bartok – The early RIAS recordings

Das Projekt einer repräsentativen, vielleicht sogar auf VollständigkeitMehr lesen

deropernfreund.de

| 37. Jahrgang, 19. Februar 2011 | Egon Bezold | February 19, 2011

Ferenc Fricsay conducts Béla Bartok – The early RIAS recordings

Die kompletten Einspielungen von RIAS Berlin

Eine lange schwere Krankheit setzt seiner dirigentischen Karriere im Alter von achtundvierzig Jahren leider ein frühes Ende. Spektakulär feierteMehr lesen

So ging Fricsay in knapp fünfzehn Jahren bis zu seinem frühen Tod für das Gelb-Label für über 150 Aufnahmen ins Studio. Eine Fricsay-Edition präsentiert 1977/78 vierzig Black Discs, die in einer exemplarischen Auswahl sein diskografisches Vermächtnis verlebendigten. Zehn CDs halten neben bekannten Titeln auch Erstveröffentlichungen fest, die auf Rundfunkproduktionen oder Live-Mitschnitten in Konzerten zurückgingen (DG 445 400). Die neue Musik findet in Fricsay einen unermüdlichen Anwalt. Er galt auch als ein Mittler für die „gemäßigte Moderne“, die seiner Meinung nach auch auf lange Sicht gesehen den Weg des Publikums zur „neueren Musik“ hätte ebnen können. Zu den Werken, die Fricsay als Erst-und Uraufführungsdirigent im Repertoire führte, gehört die glänzend instrumentierte „Französische Suite“ von Werner Egk – ein dem Dirigenten und seinem Orchester gewidmeter Kompositionsauftrag von RIAS Berlin.

Oft hat Fricsay auch Boris Blachers brillante „Paganini-Variationen“ dirigiert, und zwar mit einem eigenen Schluss, der von dem mit dem Dirigenten befreundeten Komponisten ohne Einwand akzeptiert wurde. Stereofon aufgenommen wurden zwei Kompositionen von Gottfried von Einem, das „Konzert für Klavier und Orchester op. 20“ und die „Ballade für Orchester op. 23“.

Das für klangliche Restaurierungsarbeiten von authentischem Bandmaterial aus dem Rundfunkarchiv von RIAS Berlin renommierte Label audite (remastering Ludger Böckenhoff) veröffentlicht jetzt Bedeutendes vom Ferenc Fricsay Landsmann Béla Bartók. Es handelt sich um Produktionen, die entweder live mitgeschnitten wurden im Titania-Palast Berlin oder unter Studiobedingungen in der Jesus-Christus-Kirche in Berlin entstanden. Sie stammen aus den Jahren 1950, 1951, 1952, 1953.

Mit großem geigerischen Raffinement und blendendem virtuosen Zugriff interpretiert der 2003 in der Schweiz verstorbene ungarische Geiger Tibor Varga das zweite Violinkonzert von Béla Bartók – live 1951 im Titania-Palast mitgeschnitten. Dissonante Abschnitte im Blech werden klanggeschärft ausgespielt und die Konflikte mit Alban Berg deutlich akzentuiert. Die im Anschluss an ein Festwochenkonzert 1951 mit den Berliner Philharmonikern für Deutsche Grammophon in der Jesus-Christus-Kirche entstandene Studioaufnahme soll unter Kennern – so der damalige Fricsay Assistent Csóbadi – als Referenzplatte gehandelt worden sein.

Keine Frage, dass Fricsay ein Herz für die ungarischen Komponisten zeigte, besonders für den unbekannten Bartók. Und er hob auch wahre Schätze aus der Versenkung. So erlebte „Cantata profana“ (Die Zauberhirsche) – eine bewegende Vision des Komponisten für Freiheit und Verbundenheit mit der Natur – erstmals außerhalb Ungarns unter Mitwirkung des damals sechsundzwanzigjährigen Dietrich Fischer-Dieskau eine mitreißende Aufführung. (Studioaufnahme 1951). „Musik für Saiteninstrumente, Schlagzeug und Celesta“ entstand 1952 im Studio Jesus-Christus-Kirche Berlin Dahlem in lobenswerter Geschlossenheit: farbenreich, rhythmisch gespannt und vibrierend im Finalsatz.

Schließlich erhält Bartóks fesselndes Divertimento (live mitgeschnitten 1952) – ein nach dem Concerto grosso-Stil strukturiertes Stück – alles was ihm gebührt: vibrierende emotionale Durchblutung, auch das von Geheimnis umwitterte, dynamisch fein abgestufte Wechselspiel von Soloeinwürfen mit dem vollen Orchester.

Eine eigentümliche Mischung aus ungarischen, rumänischen und arabischen Elementen ist in der fünfsätzigen „Tanzsuite“ auszumachen (Studioeinspielung 1953) – ein Auftragswerk zum 50. Jahrestag der Vereinigung von Buda und Pest. Die instrumentalen Feinheiten treten im Spiel des RIAS-Symphonie-Orchesters ebenso konturenhaft wie feinädrig in den Stimmverläufen zutage.