Das Pathos des Sachlichen. Der Pianist Friedrich Gulda in den 1950er Jahren Das Bild, das die musikalische Öffentlichkeit von Friedrich Gulda (1930-2000) hat, ist gespalten: Den einen gilt er als einer der bedeutendsten Beethoven-Interpreten des 20. Jahrhunderts, den anderen als ein Enfant...mehr

"Es ist ein rundum zu empfehlende, weil sehr glücklich machende CD-Box." (NDR Kultur)

Titelliste

Details

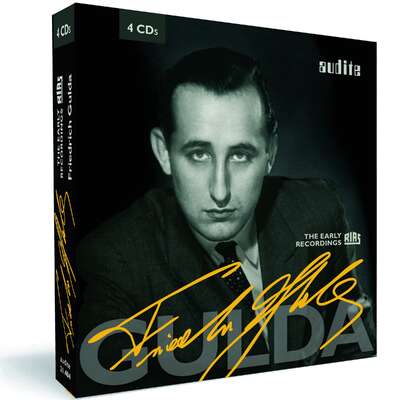

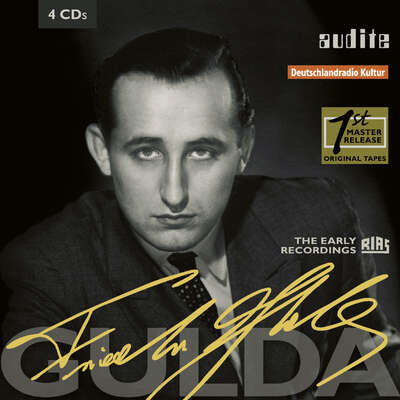

| Edition Friedrich Gulda – The early RIAS recordings | |

| Artikelnummer: | 21.404 |

|---|---|

| EAN-Code: | 4022143214041 |

| Preisgruppe: | BCT |

| Veröffentlichungsdatum: | 28. August 2009 |

| Spielzeit: | 244 min. |

Zusatzmaterial

Informationen

Das Pathos des Sachlichen. Der Pianist Friedrich Gulda in den 1950er Jahren

Das Bild, das die musikalische Öffentlichkeit von Friedrich Gulda (1930-2000) hat, ist gespalten: Den einen gilt er als einer der bedeutendsten Beethoven-Interpreten des 20. Jahrhunderts, den anderen als ein Enfant terrible, dessen Kampf gegen das kulturelle Establishment und die Begrenzung seiner vielfältigen künstlerischen Interessen und Begabungen durch die Zwänge des Konzertbetriebs legendär geworden ist. Wie immer, sind solche Zuspitzungen zugleich richtig und falsch.

Die vorliegende Zusammenstellung von bislang unveröffentlichten Aufnahmen Guldas für den RIAS Berlin zwischen 1950 und 1959 ermöglicht es, sich ein differenzierteres und vorurteilsfreies Bild des Pianisten und Musikers Gulda zu machen. Denn es tritt uns bereits hier der „komplette Musiker“ entgegen, als der sich Gulda zeitlebens empfand. Das Spektrum der Einspielungen, die angesichts der geradezu beängstigenden Konzert- und Aufnahmeaktivitäten Guldas in diesem Jahrzehnt nur die Spitze des Eisbergs darstellen, spricht für sich: Es reicht von Mozart bis Prokofiew und zeigt Gulda als einen universalen Künstler, dem es von Anfang an darum ging, größte Sachlichkeit und Texttreue mit höchster Intensität des Musizierens zu verbinden. Die Grundlage der musikalischen und pianistischen Fähigkeiten Guldas legte sein Wiener Lehrer Bruno Seidlhofer, der fast alle wichtigen Pianisten der „Wiener Schule“ formte; die Qualität von Guldas Ausbildung fand ihre Bestätigung im ersten Preis des Genfer Klavierwettbewerbs 1946, den vor ihm Arturo Benedetti Michelangeli erhalten hatte. Vorbilder für eine spontane und zugleich kontrollierte Intensität des Spiels suchte und fand Gulda dagegen im amerikanischen Jazz, dessen unaufhaltsamer Aufstieg im Europa der Nachkriegszeit ihn dauerhaft fesseln sollte. Daraus entstand die unnachahmliche Synthese eines „Pathos des Sachlichen“, die in diesen Aufnahmen zu hören ist.

Dies gilt nicht nur für die frühen Mozart- und Beethoven-Einspielungen von 1950, die Guldas fabelhaften analytischen Sinn für die kompositorischen Strukturen, seine unbestechliche rhythmische Sicherheit und Anschlagsnuancierung zeigen. Geradezu sensationell sind die Chopin- und Ravel-Einspielungen zu nennen: Pianistisch auf höchstem Niveau erfahren Chopins Préludes op. 28 und Ravels Gaspard de la Nuit dramatisch und klanglich zugespitzte Deutungen, wie sie nur selten zu hören sind. Mit seinen Interpretation zweier früher Hauptwerke Debussys, der Suite pour le Piano und der Suite Bergamasque, sowie einer Auswahl aus den Préludes erweist sich Gulda zudem als einer der wenigen Pianisten außerhalb der französischen Schule, die für diese Meisterwerke einen dezidiert modernen und doch stilgerechten Zugang fanden. Abgerundet wird das Programm durch Einzelstücke Chopins (Nocturne c-moll op. 48 Nr. 1 und Berceuse op. 60), die Guldas intensive Auseinandersetzung mit der Romantik bekunden, und eine spektakuläre Einspielung von Prokofjews Klaviersonate Nr. 7 op. 83 aus dem Jahr 1950. Prokofjews Musik, deren Wildheit nicht dauerhaft seine Sache war, führte Gulda nur wenige Jahre in seinem Repertoire, aber er gab wesentliche Impulse an seine berühmteste Schülerin, Martha Argerich, weiter.

Zu dieser Produktion gibt es wieder einen Producer's Comment – das heißt, einen unmittelbaren Eindruck des Produzenten Ludger Böckenhoff.

Die Edition Friedrich Gulda ist Teil unserer Reihe „Legendary Recordings“ und trägt das Qualitämerkmal „1st Master Release“. Dieser Begriff steht für die außerordentliche Qualität der Archivproduktionen bei audite. Denn allen historischen audite-Veröffentlichungen liegen ausnahmslos die Originalbänder aus den Rundfunkarchiven zugrunde. In der Regel sind dies die ursprünglichen Analogbänder, die mit ihrer Bandgeschwindigkeit von bis zu 76 cm/Sek. auch nach heutigen Maßstäben erstaunlich hohe Qualität erreichen. Das Remastering – fachlich kompetent und sensibel angewandt – legt zudem bislang verborgene Details der Interpretationen frei. So ergibt sich ein Klangbild von überlegener Qualität. CD-Veröffentlichungen, denen private Mitschnitte von Rundfunksendungen zugrunde liegen, sind damit nicht zu vergleichen.

Besprechungen

International Piano | May/June 2020 | Benjamin Ivry | 1. Mai 2020

Naked iconoclast

Austrian pianist Friedrich Gulda spent his career straining against the stuffier aspects of the classical music scene in a life that embraced unorthodoxy to the full. Benjamin Ivry profiles this wild child of the piano

A new series from SWR Music containing unissued radio recordings of Friedrich Gulda‘s solo recitals and concertos (see Selected Listening below)Mehr lesen

Yet differences are more striking than similarities. The puritanical Gould shunned crowded auditoriums for the pristine atmosphere of recording studios. The chain-smoking hedonist Gulda, loathing Isolation, wanted to press the flesh even more than he could at keyboard recitals. Gulda claimed to resent that the rigours of playsing classical piano required limiting his alcohol consumption. Accocding to the August 1996 issue of the jazz periodical Down Beat, Gulda once sauntered into a Vienna bar and shouted, 'Dry Martini!‘, whereupon a waiter who thought he was speaking German brought him three martinis (drei-Martinis). Down Beat gives no hint that Gulda sent back the excess booze.

Even in their intimate lives, Gould and Gulda were essentially dissimilar. Ever-secretive, Gould recorded emotive, valid renditions of lieder by Hindemith with a paramour, the Canadian vocalist Roxolana Roslak. By contrast, Gulda recorded execrable performances of Schumann lieder with a companion, Ursula Anders, and in an un-Gouldian way, traipsed onstage naked with Anders to perform them live. Alternatively, the nude Gulda would play the crumhorn, a Renaissance woodwind instrument. He alto experimented on baritone sax, hut spared audiences the sight of him tooting it ungarbed.

As a classical piano dropout, Gulda was closer to the Hungarian-American Ervin Nyiregyházi (1903-1987), who also jettisoned a concert career to experience earthier pleasures in the red-light districts of San Francisco and elsewhere. Yet Nyiregyházi languished in poverty for most of his life, unlike Gulda, whose trendy concert antics earned him enough to pay for frequent holidays in Ibiza.

This career began when Gulda‘s pianist mother urged him to lake lessons as a boy, leading to quick, and seemingly effortless, success. During the war years, Gulda and his family braved Nazi strictures to listen toAllied Army broadcasts, including jazz. Gulda always identified jazz with liberation, especially since his lifelong friend Joe Zawinul, with whom he played impromptu clandestine concerts during the war, grew up to be a jazz fusion keyboardist with Cannonball Adderley and Miles Davis. Zawinul assimilated into a milieu where Gulda remained an investigative outsider, seriously interested in the idiom, but lacking the authenticity required of jazz.

Yet Gulda considered jazz the only new music, scorning contemporary piano works by Boulez and Stockhausen, while considering Bartók and Schoenberg to be insufficiently separated from the past. He made his Carnegy Hall debut In 1950 at age 20, following three days of detention at Ellis Island after admitting that 10 years previously, he had been obliged to join a Nazi youth organisation, whose meetings he never attended. As soon as his well-received Manhattan debut was over, he hurried to Birdland, a celebrated jazz club, to hear Duke Ellington‘s orchestra.

Despite early acclaim, reviewers reminded punters that Gulda had ample competition at a time when legendary keyboard talents still thrived. In November 1951, the Musical Times compared two renditions of Beethoven‘s Sonata Op 111 in C minor, by Edwin Fischer and Gulda, from that year's Salzburg Festival, concluding that 21-year-old Gulda's showed 'insufficient maturity and depth'. Similarly, the MT of May 1956 evaluated recordings of the first book of Debussy's Préludes, complaining that despite Gulda‘s interpretive qualities, he was 'no match for [the elder Walter Gieseking's] almost miraculously perfect performance‘.

Small wonder that around the age of 30, Gulda rebelled against the elderly – performers and audiences alike. In interviews akin to rollercoaster rides of jokes, rage, and profanity, he described punters at piano recitals as 'centenarian paralytics‘ and 'stinking reactionary art lemurs' who expect to hear the same five sonatas performed ad infinitum.

On a personal level, Gulda had trouble coping with early success, which translated to chess games played against himself in lonely hotel rooms. He longed for the camaraderie of jazz clubs, in stark opposition to the chilly solitude and competitiveness of virtuoso piano careers.

As Flower Power evolved in the late 1960s and early 1970s, Gulda jumped on the bandwagon, transcribing versions of hits by the Doors and Stevie Wonder. Yet as his son Paul Gulda informed Welt am Sonntag newspaper in May 2010, the elder Gulda could be an old-fashioned choleric paterfamilias, citing an episode when Paul was around 15 and his father invited him to improvise on the recorder in the family garden. When Paul interpolated part of a Mozart symphony into his playing, his father reacted 'very contemtously', concluding, 'My son does not appreciate freedom, my son does not feel my vibes, he defaces Mozart.'

Gulda could be a nightmare faher-figure to grownups too, despite the laidback attitudes he professed to espouse. In September 1971, Helmut Müller-Brühl, director of Germany's Brühl Palace Concerts, told the New York Times that Gulda would never be invited again: '[Gulda] always get angry. He‘s difficult about money, about what he wants to eat. He‘s difficult about his music, too.‘ This tyrannical side of Gulda makes it fitting that his most famous pupil, Martha Argerich, was allowed access to him only after blurting out (aged 12) to an admirer – the Argentinian dictator Juan Perón – that her most cherished dream would be to work with Gulda. Perón made Argerich‘s studies with Gulda possible.

As past of his imperious tendencies, Gulda refused in later years to divulge recital programmes until the public was assembled, preferring to rely on spontaneity. Scorning most maestros, he insisted upon conducting from the keyboard, despite his lack of talent in leading orchestras. Yet the SWR reissues reestablish why Gulda enjoyed an early career breakthrough. A spry, impish rendition of part of Bach’s English Suite No 2 in A minor, a psychologically fragile Impromptu in A-flat major and poignant Sonata No 16 in A minor, the last two by Schubert, are impressive. Yet Gulda repeatedly stated that he was too close to the Viennese-style mindset of 'smiles and suicide' epitomised by the oft-desparing, doomed Schubert to frequent this repertoire, no matter how acutely he mastered it.

One wonders, on the other hand, if French compositions were really his cup of tea, from a limp performance of Couperin‘s L’épineuse, followed by a sketchily envisioned Second Book of Debussy's Préludes, lacking stylistic assurance. Meanwhile, his own compositions, of which Prélude and Fugue and the Doors transcription Light My Fire proved widely popular, were repetitious to a fault, although more rollicking than the usual drily sober-sided minimalism. Today, his transcriptions of pop and rock music do not seem to transcend the indigence of the original melodies.

Gulda was at his most attractive communicating domestic warmth and affection in Mozart, especially in the Sonata No 13 in B-flat major, with a final movement, marked Allegretto grazioso, like a richly imagined miseen-scène from an 18th-century stage comedy. Instinctively imagining the spirit of the rococo, Gulda also perceived its sadly fleeting aspects, like an Austrian version of the painter Watteau. He could also be a philosopher in Beethoven’s works, being drawn to the pensive Fourth Concerto and Sonata No 28 in A major. In the first movement of the latter, marked 'somewhat lively, but with intense feeling,’ Gulda appears to be asking some essential questions about mankind's motivation for existence.

Unlike these highly personalised conceptions, Gulda's version of Handel’s Suite in E minor HWV 429 sounds rather formal and anonymous. The more outlandish sides of Gulda are evident in his use of an amplified clavichord for Bach, its weired echoing twang like a puny electric guitar more suited to the Hawaiian shirts he sported onstage in later recitals, in addition to other exotic wear, than Baroque music.

On the SWR recital reissue, 30 minutes of portentous, dated sonic explorations with his jazz ensemble are included: Gulda’s Perspective No I lacks only the presence of Yoko Ono to become the definitive hippie-era waste of time. In concertos, Gulda is at his best in a January 1962 performance of Mozart’s Concerto No 14 in E-flat major conducted by Hans Rosbaud, in which the pianist manages to be fizzy and celebratory in turn. Mozart’s Concerto No 23 in A major from April 1959, also with Rosbaud, is equally fine, particularly an unadorned, moving second movement Adagio followed by a spiffy finale, marked Allegro assai.

Piano lovers may mourn that Gulda renounced artistic collaboration with the likes of Rosbaud, favouring instead onstage happenings with nubile disco dancers and Giuseppe Nuzzo, an Italian disc jockey known as DJ Pippi, who headlined at Pacha, Ibiza’s stellar nightspot. Yet we can only conclude that Gulda knew his own psychological fragilities and emotional imperatives, and followed his heart. Hie legacy, one of wilful talent and wildly uneven results, remains substantial.

Frankfurter Allgemeine Zeitung | 16.01.2017 | Gerhard R. Koch | 16. Januar 2017

Der Grenzuntergänger

Im Niemandsland zwischen Liszt und Last: Ein Rückblick auf den Wiener Pianisten Friedrich Gulda, der am liebsten zwischen allen Stühlen saß

Der junge Gulda hat zwischen 1950 und 1959 für Rias Berlin Mozart, Beethoven, Frederic Chopin, Debussy, Maurice Ravel, ja Prokofjews siebte Sonate eingespielt: makellos perfekt, virtuos ohne Allüre, bestechend stilsicher, in jeder Hinsicht kontrolliert, dabei mit energischem Drive – ein Musterschüler mit Überschuss (vier CDs bei audite). Mehr lesen

Pforzheimer Zeitung | 30.12.2011 | Thomas Weiss | 30. Dezember 2011 Guldas frühe Rundfunkaufnahmen

Dass sich Friedrich Gulda gerne als Provokateur, als Wiener Grantler oderMehr lesen

DeutschlandRadio Kultur - Radiofeuilleton | 30.12.2010 | 30. Dezember 2010

Friedrich Gulda

Historische Aufnahmen aus dem RIAS-Archiv

"Für mich ist der Gulda immer noch die Nummer 1. Der beste Pianist der Welt. Und das war er eben auch! Er hat nie falsche Töne gespielt – bei denMehr lesen

... Das habe ich nie bei einem anderen Pianisten erlebt.", erinnert sich Dorothee Ehrensberger, die ab den 1950er Jahren Musikredakteurin im RIAS war und zahlreiche Konzerte und Studioproduktionen mit Friedrich Gulda betreut hat.

Aus diesem umfangreichen Archivschatz senden wir heute einen kleinen Teil, ausschließlich Aufnahmen, die bislang unveröffentlicht sind, aus den Jahren 1965 bis 1971. Darunter auch eine Version der Sonate B-Dur op. 106, der sogenannten Hammerklaviersonate von Ludwig van Beethoven, für die Friedrich Gulda im Herbst 1967 von seiner üblichen Aufnahmestrategie abwich: eine Hammerklaviersonate hatte er angekündigt, die selbst er so im Konzert nicht spielen könnte. Und so erarbeiteten Pianist und Tonmeister vor der Aufnahme einen Schnittplan – 5 Tage und knapp 200 Schnitte später war die Einspielung perfekt.

Klaus Bischke war damals Tonmeister, er und Dorothee Ehrensberger erinnern sich an diese und andere Produktionen. Auch Gulda selbst kommt zu Wort: was seine Art, Mozart zu spielen, dem Jazz zu verdanken hat, ist da unter anderem zu erfahren, in einem Interview zum Thema "Auszierungen – Verzierungen", das er im April 1967 nach seiner Aufnahme der Sonate C-Dur KV 545 gegeben hat.

Grandios dokumentiert im RIAS-Archiv: ein geradezu unglaublicher Zugabenmarathon zum Abschluss eines Konzerts in der Berliner Philharmonie am 10. November 1971 mit Johann Sebastian Bachs Wohltemperiertem Klavier. Das war seine letzte Aufnahme für den RIAS.

Ein Porträt Friedrich Guldas, zusammengestellt aus Studioaufnahmen und Konzertmitschnitten: Klassik, Jazz - und jede Menge Gulda.

France Musique | mercredi 15 décembre 2010 | Frédérique Jourdaa | 15. Dezember 2010 BROADCAST Le point du jour

Sendebeleg siehe PDF!Mehr lesen

France Musique | mardi 14 décembre 2010 | Frédérique Jourdaa | 14. Dezember 2010 BROADCAST Le point du jour

Sendebeleg siehe PDF!Mehr lesen

American Record Guide | May-June 2010 | Alan Becker | 1. Mai 2010

Although a product of the Vienna Music Academy, which he entered at the age of 12 to study under Bruno Seidlhofer and Joseph Marx, Gulda wasMehr lesen

These recordings of the pianist in his 20s give us an opportunity to review his early accomplishments in the classical repertory. After being without these for many years, it was refreshing to hear them once again and resp[ond to some grand and astonishing music-making. The sound is generally fine— clear and warm, if close and monaural.

The Beethoven sonatas (10, 28, 30), Eroica Variations, and 32 Variations in C minor are sometimes brusque, with sharp accents and wide contrasts. They are not, however, out of keeping with what we know of Beethoven’s personality. The beauty of the composer’s slow sections is not slighted in the least, as Gulda’s marvelous concentration and phrasing come fully to the fore. Also present, as in the final movement of Sonata 10, is Beethoven’s sense of humor—this Scherzo rides the wind with gale speed.

Debussy’s Pour le Piano, Suite Bergamasque, and the few excerpts from the Preludes, Estampes, and Images are not patted down with layers of Impressionist gauze. They are very direct—forceful and impetuous. They are also, as in the final ‘Toccata’ from Pour le Piano virtuosic to the extreme. Gulda plays all of this music full out. The famous ‘Clair de Lune’, while refined, grows heavy with nostalgia as it unfolds its beauty; but these along with Ravel’s Gaspard de la Nuit show the artist considerably short of the imagination needed to be fully convincing.

The 24 Chopin Preludes do not find the pianist at his most persuasive. While there are certain niceties, Prelude 3 uses the pedal too much, causing a smear in the rippling left hand. Prelude 10, on the other hand, is most spirited, with the right hand always sparkling. Prelude 11 has perhaps more expressive rubato then it needs, while the ensuing Presto of Prelude 12 is driven and choppy, as it should be. The Allegro of Prelude 14 is thrilling, especially with its spare use of pedal and clearsounding organized chaos. Prelude 15 (Raindrop) begins daintily but soon finds Gulda, drenched with emotion, squeezing everything he can get out of the piece. The violence of Prelude 18 is well conveyed as it seizes one by the throat until its energy has been spent. The gentle but speedy 19th Prelude is just about perfect—one of the best I have heard—but the very last of the set puts you through the emotional wringer once again. In all, a mixed bag.

Chopin’s Nocturne in C minor, Op. 48:1, is not a laid-back performance. It moves in a positive way, and the contrasting stormy middle section is most effectively realized. The Barcarolle, on the other hand, is uneven, with rhythms that may be pulled about too much for some tastes. On the positive side, it’s certainly a big-boned approach to one of the composer’s finest compositions.

Prokofieff’s wartime Sonata 7 is appropriately demonic, with the final ‘Precipitato’ hammering away towards its violent conclusion. There is a respite in the slow movement’s lyricism, though the dark clouds are never far away.

Recorded in 1950, the sound can be a bit murky when razor-sharp vividness is what’s really called for.

The only work with orchestra in this set is Mozart’s dramatic Concerto 24 in C minor. Markevitch conducts with all the drama one could wish for, but the overall sound is astringent, with a sour sound in the oboes. All this is of small matter in view of the stirring musicmaking of Gulda. Wolfgang Rathert’s essays contribute substantially to the value of this album.

www.critic-service.de | 30. März 2010 | Christian Ekowski | 30. März 2010

Diese Box mit 4 CDs des Pianisten Friedrich Gulda ist ein überausMehr lesen

Wochen-Kurier | Mittwoch, 10. Febraur 2010 Nr. 6 | Michael Karrass | 10. Februar 2010

Die audite Produktion 21404 "Edition Friedrich Gulda – The early RIASMehr lesen

Musica | febbraio 2010 | Riccardo Risaliti | 1. Februar 2010

L'articolista di questo album, Wolfgang Rathert, parte da un'acuta analisiMehr lesen

www.codaclassic.com | February 2010 | 1. Februar 2010 Edition Friedrich Gulda - The early RIAS recordings

koreanische Rezension siehe PDFMehr lesen

BBC Music Magazine | February 2010, Vol 18 Number 6 | Andrew Mc Gregor | 1. Februar 2010

Historic Friedrich Gulda

Andrew McGregor, presenter of CD Review, reviews two sets which commemorate the eccentric pianist

These two sets illuminate the outer ends of Friedrich Gulda’s career; the Berlin radio recordings he made throughout his 20s, then, following hisMehr lesen

The Early RIAS Recordings (Audite 21.404: 4 CDs) begin in 1959 with Beethoven Sonatas Op. 14 No. 2, and Op. 109 in whose finale Gulda lacks the singing intensity that he finds in his 1967 cycle. The Eroica Variations, though, are gripping, even blisteringly paced. Debussy’s Pour le piano has a bold and brilliant opening. The gibbet in Ravel’s Gaspard de la nuit lacks mesmerising menace, but ‘Scarbo’ has vital electricity. Chopin’s Preludes swing from introverted intensity to explosive violence. Gulda was 19 when he recorded Prokofiev’s Sonata No. 7, yet seems ill-at-ease with its modernism. But his Mozart C minor Concerto K491, with Igor Markevitch conducting in 1953, has a disciplined precision that’s bracing, especially with Hummel’s brilliant cadenzas.

Gulda returned to the classical concert platform in 1981 with three complete cycles of Mozart sonatas in Munich, Paris and Milan. Private recordings were made the following year in a lakeside hotel near Salzburg; only cassette copies survive as the masters disappeared. The Complete Gulda Mozart Tapes (DG 477 8466; 6 CDs) combines the two previously released volumes, with the distortion that marred two of the sonatas electronically tamed so that the cycle is now complete (Gulda’s son Paul plays the missing 30 seconds from the recording of K457). The sound is clean and dry, intimate in the slow movements but unforgivingly brilliant elsewhere. The bass lines have a joyful drive, there’s a keen sense of forward momentum but little sign of the improvisatory freedom Gulda sought in jazz – until you reach the concert performances on the bonus disc. From 1978 there’s a Musikverein performance of the K397 Fantasia which emerges from Gulda’s own Mozartian fantasy, and from 1997 a Mozart Adagio with synthesized strings; a dated sound, but lovingly achieved. Gulda said that when he was dead, he hoped to play piano duets with Mozart; perhaps in his mind they’d have sounded like this. He died three years later, on Mozart’s birthday.

Diapason | février 2010 | Etienne Moreau | 1. Februar 2010

Friedrich Gulda enregistra pour Decca dès 1950, mais hormis son intégrale Beethoven, le label britannique ne nous a jamais vraiment rendu sesMehr lesen

Un sentiment d'austérité ressort de ces Beethoven un peu doctes (Opus 109), parfois raides (Variations « Eroica »), ou de ces Chopin pressés (Préludes). On préfère le disque de musique française, où il se lâche un peu plus, comme dans la Suite bergamasque de Debussy, et un Gaspard de la nuit raffiné mais manquant de puissance (Scarbo). Le plus incontestable ici reste Mozart, représenté par un Concerto KV491 exemplaire que dirige un Markevitch inspiré. Et le plus inattendu est cette Sonate n° 7 de Prokofiev menée bon train mais d'une étonnante sobriété dans la réalisation. Si l'aspect pianistique est intéressant, tout cela est quand même un peu sévère, et ne porte pas encore la marque de la liberté flamboyante qui sera plus tard la signature de Gulda.

Die Presse | 28. Januar 2010 | Wilhelm Sinkovicz | 28. Januar 2010

Der junge Gulda. Seine ersten Aufnahmen verraten, welcher Heißsporn dieserMehr lesen

Mannheimer Morgen | Dienstag, 29.Dezember 2009 | Alfred Huber | 29. Dezember 2009

Kühl kontrollierte Leidenschaft

Der Pianist Friedrich Gulda begeistert mit frühen, bislang unveröffentlichten Aufnahmen aus dem RIAS-Archiv

Ein Exzentriker. Von Anfang an, privat wie musikalisch. Auch wenn die jetztMehr lesen

Deutschlandfunk | Die neue Platte vom 27.12.2009 | Norbert Hornig | 27. Dezember 2009

BROADCAST Die neue Platte: Zurück in die Vergangenheit

Historische Aufnahmen

[…] Haben große Schallplattenfirmen wie EMI, Sony oder Deutsche Grammophon bereits einen großen Teil ihrer diskografischen Schätze gehoben undMehr lesen

Audite hat seinen Katalog mit historischen Aufnahmen aus Rundfunkarchiven auch in diesem Jahr mit vielen Highlights bereichert und etwa die Editionen mit den Dirigenten Karl Böhm, Ferenc Ficsay und Igor Markewitsch weiter ausgebaut. Für besonderes Aufsehen sorgten aber die Veröffentlichungen sämtlicher RIAS-Aufnahmen mit den Berliner Philharmonikern unter der Leitung von Wilhelm Furtwängler und die Aufnahmen, die der junge Friedrich Gulda zwischen 1950 und 1959 für den RIAS Berlin machte. In einem vielgestaltigem Programm begeistert Gulda dabei nicht nur mit Werken von Beethoven, Debussy, Ravel und Prokofieff, sondern auch als raffinierter Chopin-Interpret:

"05. MUSIK: Frédéric Chopin

Prélude Nr. 3 G-Dur (Vivace)

Friedrich Gulda (Klavier)

LC 04480 Audite 21.404"

Während es sich bei den frühen RIAS-Aufnahmen Friedrich Guldas um Erstveröffentlichungen handelt, sind Wilhelm Furtwänglers RIAS-Aufnahmen mit den Berliner Philharmonikern, die zwischen 1947 und 1954 entstanden, in Sammlerkreisen weitgehend bekannt, u.a. von nicht autorisierten Raubpressungen. Wie bei allen historischen Veröffentlichungen von Audite wurden für die Digitalisierung nur die Originalbänder verwendet, wobei auch problematische Tonhöhenschwankungen korrigiert wurden. Auf 12 CDs ist hier Furtwänglers Spätstil dokumentiert, wobei die Symphonik von Beethoven, Brahms und Bruckner im Zentrum steht. Aber auch als Dirigent neuerer Werke ist Furtwängler zu erleben, mit einem Repertoire, dass man mit seinem Namen nicht unmittelbar in Verbindung bringt, etwa die "Concertante Musik für Orchester" von Boris Blacher:

"06. MUSIK: Boris Blacher

Concertante Musik für Orchester op. 10 (Ausschnitt)

Berliner Philharmoniker

Leitung: Wilhelm Furtwängler

LC 04480 Audite 21.403 "

klassik.com | 17. Dezember 2009 | Dr. Daniel Krause | 17. Dezember 2009 | Quelle: http://magazin.k... Vermächtnis mit neunzehn

Vor zehn Jahren lancierte Friedrich Gulda die Nachricht vom eigenen Tod.Mehr lesen

Die Zeit | 10. Dezember 2009 Nr. 51 | Wolfram Goertz | 10. Dezember 2009

Die auf ein neues Talent aufmerksam machen

Friedrich Gulda: The Early Rias-recordings

Furioses Klavierspiel eines jungen Österreichers. Beethoven alsMehr lesen

www.hifistatement.net | 3. Dezember 2009 | Attila Csampai | 3. Dezember 2009 Der junge Gulda in Westberlin

Guldas „Geist“ spukt wieder: Nach den privaten Mozart-Tapes und denMehr lesen

Scherzo | diciembre 2009 | Enrique Pérez Adrián | 1. Dezember 2009 Gulda y otras joyas

El sello alemán Audite (distribuidor: Diverdi) nos trae un nuevoMehr lesen

Diverdi Magazin | 187/ diciembre 2009 | Ignacio González Pintos | 1. Dezember 2009

El dios de las pequeñas cosas

Audite reúne en un estuche de cuatro CDs, con una primorosa reconstrucción sonora, las primeras grabaciones del gran pianista austríaco Friedrich Gulda

“En el caso de Gulda, el afán de objetividad no es tanto un fin en sí mismo como el marco desde el que desarrollar una nueva subjetividad.Mehr lesen

Nuestra época es esencialmente trágica, y precisamente por eso nos negamos a tomarla trágicamente. El cataclismo ya ha ocurrido, nos encontramos entre ruinas, empezamos a construir nuevos y pequeños lugares en que vivir, comenzamos a tener nuevas y pequeñas esperanzas. No es un trabajo fácil. No tenemos ante nosotros un camino llano que conduzca al futuro. Pero rodeamos o superamos los obstáculos. Tenemos que vivir, por muchos que sean los cielos que hayan caído sobre nosotros.

D. H. Lawrence, El amante de Lady Chatterley

El proceso de reconstrucción que testimonia la segunda posguerra europea no podía limitar sus esfuerzos a la urgente rehabilitación material, también debía ocuparse de conjurar los demonios del mundo espiritual, crear vínculos y referencias diferentes, arropar con nuevos valores el pasado susceptible de ser recuperado y abrir perspectivas desde las que atreverse a saludar el futuro. Comienza así en el ámbito de la interpretación musical la depuración de una herencia grandilocuente y sospechosa, la deconstrucción de una tradición con resonancias funestas.

Ganador del concurso de Ginebra en 1946 y artista con contrato en Decca desde 1948, el pianista Friedrich Gulda se presentaba en New York en 1950 tras haber realizado sendas giras por Europa y Sudamérica los años precedentes. Hasta setenta conciertos ofreció ese mismo año un Gulda que había demostrado poseer el talento y la inteligencia para convertirse en símbolo de la nueva y renovadora escuela pianística vienesa.

Una renovación que exigía el regreso desintoxicado a las fuentes o, cuando menos, una intoxicación alternativa de las mismas. Porque, en el caso de Gulda. el afán de objetividad no es tanto un fin en sí mismo como el marco desde el que desarrollar una nueva subjetividad. Intérprete personal, no fue ajeno al capricho y la provocación, profesando incluso cierto culto por la originalidad. Pero Gulda representó a la perfección el emergente modelo de intérprete, el del intelectual que desde una perspectiva estudiada y crítica mantiene en su aproximación una cierta distancia academicista. Nace una estética sin vocación trascendental, ajena a cualquier tipo de compromiso con el público; una sensibilidad que no invoca grandes ideales ni procura encender el ánimo colectivo, un individualismo de apariencia hermética que desde el rigor conceptual evita lugares comunes y se esfuerza en compartir su fascinación por las pequeñas cosas.

Este estuche Audite ofrece un episodio hasta ahora inédito de ese ejercicio de depuración, cuatro discos que reúnen grabaciones en estudio realizadas durante la década de los cincuenta por un Gulda en su apogeo mediático e interpretativo, donde el sonido conserva todo el brillo v la audacia juveniles y el concepto es todavía fresco, oportuno y pertinente.

Ludwig van Beethoven había de convertirse, necesariamente, en el epicentro de la pretendida reforma estilística. Fue además el auténtico caballo de batalla de Gulda, que registró tres ciclos completos de sus sonatas. La pulcritud en la articulación, el énfasis rítmico y el timbre brillante presiden una sonoridad en la que el pedal es un recurso aislado que no llega a integrarse en un discurso ágil, de líneas clarísimas y estructura visible. Lo que subyace es la intención de derribar la imagen idealizada del genio que sólo atiende a la llamada de su destino creador para presentarnos a un Beethoven sonriente que dialoga con su público, que desea ser entendido y escuchado en los hogares de su tiempo. No encontrará el lector rastro alguno de olimpismo en el fraseo de Gulda, tampoco ecos de carácter heroico en los marcados ritmos, ni patética desolación en sus tiempos lentos. Sí, en cambio, una amplia y conseguida gama de emociones domésticas, expresadas con delicada sensibilidad en una apuesta por el Beethoven más comercial y humorístico – Sonata 10, op. 14/2 – , el de escritura dulce y graciosa – Sonata 30, op. 109 – , el un Beethoven que no pierde simpatía ni cuando se obstina – Sonata 28. op. 101 – . Unas variaciones atléticas y de fino impulso completan un particular, luminoso y refrescante cuadro beethoveniano.

Pasiones también domésticas dominan el clima de los Preludios de Chopin, toda vez que la interpretación prescinde del aliento romántico en busca de la modernidad de las piezas. Muy en la línea de la recientemente reeditada en CD versión de Anda del mismo año en cuanto a claridad expositiva, delicadeza (imbrica y carácter casi impresionista, el acercamiento de Gulda posee un puntillismo en ocasiones algo afectado que permanece ausente de la más distinguida lectura del húngaro. Nocturno y Barcarola son ejecutados, por contra, con un más canónico estilo, sin merma de la transparencia y la atención al detalle. El Debussy sorprende por el firme ímpetu y la exactitud métrica que Gulda impone a una selección de piezas que por su definido sonido y por su muy sugerente juego tímbrico se convierten en una de las grandes bazas de esta edición. Algo parecido cabría decir de un Gaspard de la nuit de Ravel que, sin embargo, pierde poder de fascinación a lo largo de un discurso en ocasiones algo confuso. Una Séptima sonata de Prokofiev algo desfigurada se convierte en la nota exótica de este capítulo guldiano.

Cerramos el repaso con el Concierto para piano n° 24 de Mozart, una de las joyas de este cofre. Igor Markevitch dirige a la orquesta de la RIAS con pulso incisivo, precisión en el refinado diálogo orquestal y estilizado dramatismo, abriendo un espacio ideal para que Gulda exponga su pulsación brillante, su fraseo sutil y calculado. Si Beethoven supone un caballo de batalla, Mozart, al que Gulda volvía una y otra vez, luce como un idílico refugio en el que reina el orden, quizá porque la exquisita sencillez del lenguaje mozartiano es el auténtico lenguaje del dios de las pequeñas cosas.

Un último comentario acerca de la estupenda restauración sonora, a partir de las cintas originales procedentes de los archivos de la RIAS, que han realizado los ingenieros de Audite. Apenas hay diferencias entre las distintas tomas, limpias y espaciosas, en las que se aprecia todo el brillo del piano de Gulda. El ligerísimo soplido de fondo es imperceptible y sólo cierto endurecimiento del sonido a partir del/orte puede limitar muy puntualmente el placer de la escucha. El sello alemán pone a disposición del internauta diverso material adicional – fotografías, recortes de prensa, actas de las sesiones de grabación, una reseña radiofónica de esta edición y dos archivos audio del propio Gulda hablando de Bach y Cortot – que pueden consultarse y descargarse desde la página http://www.audite.de/.

Fono Forum | Dezember 2009 | Norbert Hornig | 11. November 2009 Historische Aufnahme des Jahres

Sämtliche RIAS-Aufnahmen mit Wilhelm Furtwängler (live) und die frühen RIAS-Aufnahmen mit Friedrich Gulda. Kostbarkeiten aus dem Rundfunkarchiv,Mehr lesen

La Musica | November 2009 | 1. November 2009

Rezension siehe PDFMehr lesen

Gramophone | November 2009 | 1. November 2009

Gulda and Richter

A Beethoven performance that convinces in its 'rightness'

There are some recorded performances that spell "rightness" with such unflinching certainty that for the duration you're hoodwinked into believingMehr lesen

By contrast Gulda's bright and crisply articulated account of Mozart's great C minor Concerto, K491 (with Hummel's cadenzas) looks forward to a later age, much abetted by Igor Markevitch's clear-headed conducting. Gulda also offers a dark and at times relentless account of Prokofiev's Seventh Sonata while an all-French programme includes performances of Debussy's Pour le piano and Suite bergamasque, together with shorter pieces, that combine murmuring passagework with vital delivery of the more rhythmic numbers, qualities that also enhance the effect of Ravel's Gaspard de la nuit. And there are the other Beethoven works, the sonatas Opp 14 No 2 (especially engaging) and 109, and the Variations, Op 35 (Eroica) and in C minor. I read from the comprehensive notes that Austrian Radio holds a complete Beethoven sonata cycle from 1953, which would I'm sure be gratefully received by piano aficionados. No need to ask for Sviatoslav Richter recordings: the market is positively flooded with them. And yet one new release from West Hill Radio Archives offers a "fabled" concert (their claim) given at the Budapest Academy of Music in February 1958.

Pictures at an Exhibition is fairly similar to the uncompromisingly direct account put out by Philips (same period) but the real find is Schubert's late C minor Sonata, D958, which is both impetuous and at times delicate. The finale has something of the Erlking's ferocity about it and there are shorter pieces by Rachmaninov and Debussy. The sound is dry but clear.

CD Compact | noviembre 2009 | Benjamín Fontvella | 1. November 2009

He aquí un modélico álbum de homenaje a uno de los pianistas másMehr lesen

Stereoplay | November 2009 | Attila Csampai | 1. November 2009

Früh vollendeter Exzentriker

Alle Jahre wieder zur Hauptverkaufszeit ruft sich Gulda der „Unsterbliche“ mit Privataufnahmen und Archivfunden in Erinnerung. Jetzt mit der CD-Premiere seiner frühen RIAS-Aufnahmen.

Die Dokumente, die seit dem Tod Friedrich Guldas (2000) veröffentlichtMehr lesen

Mitteldeutscher Rundfunk | MDR Figaro - Take 5, 26.10.2009 | 26. Oktober 2009

In seinem Nonkonformismus wurde er mit Glenn Gould verglichen, Peter CosséMehr lesen

Stereoplay | Oktober 2009 | Michael Stegemann | 1. Oktober 2009

„Bis ins letzte ausgeschliffen, jedoch etwas zu sehr mit unpersönlicher,Mehr lesen

Pizzicato | N° 196 - 10/2009 | Alain Steffen | 1. Oktober 2009 Gulda, der Erneuerer

Nach dem 2. Weltkrieg hat besonders die jüngere Generation von Musikern einen Wechsel herbeigesehnt und auch herbeigeführt. Bei den Komponisten kamMehr lesen

International Record Review | October 2009 | 1. Oktober 2009

Igor Markevitch was at the height of his powers in the early 1950s and two discs of broadcast recording' with the RIAS SO, Berlin, have appeared onMehr lesen

The second disc is more interesting. It opens with the Suite No. 2 from Daphnis et Chloé by Ravel. This is very fine indeed, with Markevitch at his most engaged and expressive, and it's good to have the chorus parts included too. Stravinsky's Le Sacre du printemps was always one of this conductor's great specialities (he made two EMl studio recordings of the work in the 1950s alone) and here we have a live 1952 version that is staggeringly exciting and very well played. Few other conductors could deliver such thrilling versions of the Rite in the 1950s, but Ferenc Fricsay was assuredly one of them, and this was, after all, his orchestra (their own stunning DG recording was made two years after this concert). After this volcanic eruption of a Rite, the final item on the disc breathes cooler air: the Symphony No. 5 (Di tre re) by Honegger. Warmly recommended, especially for the Stravinsky (Audite 95.605, 1 hour 13 minutes).

Michael Rabin's too-short career is largely documented through a spectacular series of studio recordings made for EMI, but these never included the Bruch G minor Concerto. Audite has issued a fine 1969 live performance accompanied by the RIAS SO, conducted by Thomas Schippers, transferred from original tapes in the archives of German Radio. Rabin's virtuosity was something to marvel at but so, too, was his musicianship. His Bruch is thoughtful, broad , rich-toned and intensely satisfying. The rest of the disc is taken up with shorter pieces for violin and piano. The stunning playing of William Kroll's Banjo and Fiddle is a particular delight, while other pieces include Sarasate's Carmen Fantasy and Saint-Saëns's Havanaise. Fun as these are, it's the Bruch that makes this so worthwhile (Audite 95.607, 1 hour 10 minutes).

There have been at least three recordings of the Brahms Violin Concerto with Gioconda De Vito (1941 under Paul van Kempen, 1952 under Furtwängler and a 1953 studio version under Rudolf Schwarz), but now Audite has unearthed one with the RIAS Symphony Orchestra, conducted by Fricsay. Recorded in the Jesus-Christus-Kirche on October 8th, 1951, this is a radiant performance. De Vito's rich sound is well caught by the RIAS engineers and the reading as a whole is a wonderful mixture of expressive flexibility within phrases and a strong sense of the work's larger architecture. In this very fine account she is much helped by her conductor: Fricsay is purposeful but fluid, as well as propulsive in both the concerto and the coupling: Brahms's Second Symphony, recorded a couple of years later on October 13th, 1953. This is just as impressive: an imaginatively characterized reading that is affectionately shaped in gentler moments (most beautifully so at the end of the third movement) and fiercely dramatic in the finale. The mono sound, from the original RIAS tapes, is very good for its age. A precious disc celebrating two great artists (Audite 95.585, 1 hour 20 minutes).

Friedrich Gulda's playing from the 1950s is documented through a series of Decca commercial recordings and some fine radio recordings, including a series made in Vienna on an Andante set (AN2110, deleted but still available from major online sellers). I welcomed this very warmly in a round-up when it appeared in 2005, and now Audite has released an equally interesting anthology of Gulda's Berlin Radio recordings. Yet again, here is ample evidence of the very great pianist Gulda was at his best. There is only occasional duplication of repertoire, such as the 1953 Berlin Gaspard de la nuit by Ravel, and Debussy's Pour le piano and Suite bergamasque, immensely refined and yet strongly driven in these Audite Berlin recordings, though 'Ondine' shimmers even more ravishingly in the 1957 Vienna performance (but that's one of the greatest Gaspards I've ever encountered). The opening Toccata from Pour le piano has real urgency and tremendous élan in both versions. The Chopin (from 1959) includes what I believe is the only recording of the Barcarolle from this period in Gulda's career (two versions exist from the end of his career) – it grows with tremendous nobility and Gulda's sound is marvellous, as is his rhythmic control – it’s never overly strict but the music's architecture is always apparent. This follows the 24 Préludes. Gulda's 1953 studio recording has been reissued by Pristine, and this 1959 broadcast version offers an absorbing alternative: a deeply serious performance that captures the individual character of each piece with imagination and sensitivity.

The Seventh Sonata of Prokofiev was taped in January 1950, just over a year after Gulda had made his studio recording of the same work for Decca (reissued on 'Friedrich Gulda: The First Recordings', German Decca 476 3045). The Berlin Radio discs include some substantial Beethoven: a 1950 recording of the Sonata, Op. 101 and 1959 versions of Op. 14 No. 2, Op. 109, the Eroica Variations. Op. 39 and the 32 Variations in C minor, WoO80. Gulda's Beethoven has the same qualities of rhythmic control (and the superb ear for colour and line) that we find in his playing of French music or Chopin, and the result is to give the illusion of the music almost speaking for itself. The last movement of Op. 109 is unforgettable here: superbly song-like, with each chord weighted to perfection. Finally, this set includes Mozart's C minor Piano Concerto, K491, with the RIAS SO and Markevitch from 1953 – impeccably stylish. This outstanding set is very well documented and attractively presented (Audite 21.404, four discs, 4 hours 5 minutes).

Rondo | Nr. 594 / 26.09. - 02.10.2009 | Guido Fischer | 25. September 2009

Von Friedrich Gulda ist die Forderung überliefert, dass ein klassischerMehr lesen

Die Presse | Schaufenster | 25.09.2009 | Wilhelm Sinkovicz | 25. September 2009

2010 wäre Friedrich Gulda 80 geworden. Rechtzeitig erschien bei AuditeMehr lesen

NDR Kultur | Feuilleton | Neue CDs | 21.09.2009 15:30 Uhr | Elisabeth Richter | 21. September 2009

Frühe RIAS-Aufnahmen von Friedrich Gulda

Aufnahmen von 1950, 1953 und 1959

Friedrich Gulda ist ein Künstler gewesen, der sich in kein Schema pressen lassen wollte, ein phänomenal begabter klassischer Pianist, einMehr lesen

Charme und Zauber

"Ich bin der wichtigste kreative Musiker der zweiten Hälfte unseres Jahrhunderts", sagte Gulda einmal in einem Interview. Von mangelndem Selbstbewusstsein zeugt so ein Satz gewiss nicht. Man sagte Gulda Unbescheidenheit und Überheblichkeit nach. Man konnte aber ganz deutlich unter dieser Oberfläche eine sehr zarte und verletzliche Seele spüren. Anders ließe sich Guldas überirdisches Mozart-Spiel etwa kaum erklären. Man kann es in der CD-Box bei Mozarts c-Moll-Klavierkonzert hören. Aber interessanter noch sind die Chopin-Aufnahmen.

Charme und Zauber konnte Gulda vermitteln, und dass man ihn gern als sachlichen Pianisten klassifiziert, das trifft nur auf manche der 24 Chopin-Preludes zu. Es ist angenehm, dass Kitsch und romantisches Pathos nicht seine Sache waren. Wird es virtuos bei Chopin, greift Gulda durchaus beherzt in die Tasten - da gab und gibt es Pianisten, die sauberer und genauer in der Virtuosität sind. Das war vielleicht ein Grund, warum Gulda später kaum Chopin spielte, und gerade deshalb ist diese CD-Box so wertvoll, die eine Chopin-CD enthält.

Eine glücklich machende CD-Box

Beethoven und Mozart fallen einem bei Gulda zuerst als seine bevorzugten Komponisten ein, weniger ist bekannt, mit welchem Feinsinn Gulda die Impressionisten Ravel und Debussy spielte. So differenziert, so genau artikuliert, dabei analytisch und schillernd zugleich, raffiniert alle Möglichkeiten des Klavierklangs ausnützend - so subtil spielen Debussy nur wenige Pianisten. Ein weiterer Glücksfall dieser Box sind also die Debussy und Ravel-Aufnahmen.

Guldas "Paradepferd" Beethoven ist natürlich auch gebührend vertreten, mit den nicht allzu oft gebotenen Eroica-Variationen, den späten Sonaten A-Dur und E-Dur, und der frühen G-Dur- Sonate op. 14. Gulda präsentiert Beethoven in diesen Aufnahmen aus den 50er-Jahren weit radikaler, trockener, kompromissloser als später.

Es ist ein rundum zu empfehlende, weil sehr glücklich machende CD-Box.

Bayern 4 Klassik - CD-Tipp | 16.09.2009 | Bernhard Neuhoff | 16. September 2009 Friedrich Gulda – The early RIAS recordings

In den ersten Jahren nach seinem Tod im Januar 2000 blieb Friedrich Gulda vor allem als Exzentriker im Gedächtnis. Man hatte in frischer Erinnerung,Mehr lesen

Heute hat sich der Nebel um den Provokateur, den Wiener Grantler, das enfant terrible (und wie die Klischees noch heißen mögen) merklich gelichtet. Dadurch wird der Blick endlich wieder frei fürs Wesentliche. Und das ist eine Tatsache, die Gulda im Eifer des Gefechts manchmal vielleicht selbst ein wenig aus den Augen verloren hatte – nämlich dass er als Klassikinterpret einer der größten, für mich persönlich: der größte Pianist seiner Zeit war.

Unerschöpfliche Energie

In der bei audite erschienen Box mit vier CDs werden nun erstmalig Aufnahmen veröffentlicht, die der junge Gulda in den Jahren von 1950 bis 1959 für den RIAS machte, den von der amerikanischen Schutzmacht finanzierten Radiosender in West-Berlin. Und wieder einmal kann man staunend erleben, dass Gulda die Bühne als fertiger Künstler betreten hat, mit einem Repertoire, das von Mozart, Beethoven und Chopin über die französischen Impressionisten bis zu Prokofjew reicht. Von Anfang an scheint Gulda keine technischen Grenzen gekannt zu haben, von Anfang an überragte er seine Altersgenossen durch ein schier unerschöpfliches Reservoire an musikalischer Energie, gepaart mit einer ebenfalls überragenden interpretatorischen Intelligenz.

Kompromisslos objektiv

Diese hellwache musikalische Auffassungsgabe fesselt durch eine unverwechselbare Radikalität, die Gulda sofort kenntlich macht: So spielt kein anderer. Aber – und das unterscheidet ihn fundamental von anderen nonkonformistischen Künstlern seiner Generation wie etwa Glenn Gould, mit dem er immer wieder verglichen wurde – bei Gulda hat diese Radikalität nichts von Willkür, nichts von subjektiven Launen. Stattdessen war er stets kompromisslos den Intentionen des Komponisten auf der Spur. Und so setzt er sich bereits in den frühen 50er Jahren als junger Wilder ganz bewusst ab vom Typus des romantischen Virtuosen, der sich auf Innerlichkeit, Gefühl und Inspiration beruft. Gulda schreibt sich Objektivität auf die Fahnen, vom "Pathos der Sachlichkeit" spricht treffend der informative Booklet-Text.

Zorniger junger Mann

Insofern präsentiert sich der junge Gulda hier als einer jener "angry young men", die gegen den damals vorherrschenden kulturellen Konservatismus ankämpften. Die Generation der Väter war in den Augen dieser zornigen jungen Männer durch den Krieg und das, was zu ihm geführt hatte, zutiefst diskreditiert. Bei Gulda mag jener Nonkonformismus jedoch noch tiefere Wurzeln haben. Den Impuls, sich vom selbstherrlichen Gehabe der großen romantischen Virtuosen abzusetzen, verdankt er nicht zuletzt seinem Lehrer Bruno Seidlhofer. Der wiederum war ein Schüler von Arnold Schönberg und Alban Berg. Mit der Musik der Zweiten Wiener Schule hat Gulda zwar nichts anfangen können, sein Interpretations-Ideal ist jedoch – vermittelt durch seinen Lehrer – stark von Schönbergs Ideen geprägt. Man könnte auch an andere Protagonisten der Wiener Moderne denken, etwa an Karl Kraus, der gegen Phrase und hohles Pathos in der Sprache kämpfte. Insofern steht Gulda durchaus in einer spezifisch wienerischen Tradition.

Lust am Ausdruck

Allerdings zeigt sich der junge Gulda noch vergleichsweise konziliant – vor allem, wenn man die jetzt neu veröffentlichten Beethoven-Interpretationen mit der bekannten Gesamteinspielung von 1968 vergleicht. Bei diesen frühen Aufnahmen, und das macht ihren besonderen Reiz aus, spielt Gulda weniger unerbittlich im Tempo. Dieser Beethoven kennt auch spielerische und charmante Seiten; man spürt eine noch ganz unbefangene Lust an der Expression, die das rigorose Streben nach Texttreue glücklich ausbalanciert.

Entrümpelungs-Furor

Besonders interessant wird die Box durch eine Gesamteinspielung von Chopins Preludes op. 28. Hier zeigt sich eindrucksvoll der Entrümpelungs-Furor des jungen Gulda – und der führt überraschenderweise ganz nah an Chopin heran. Die Preludes sind ja allesamt hochoriginelle Miniaturen, jedes perfekt organisiert und manchmal geradezu verstörend in ihrer Kompromisslosigkeit. Der junge Gulda nimmt jede einzelne Nummer bedingungslos ernst. Mit Nachdruck befreit er Chopin vom Geruch des Salonkomponisten, von allen weichlichen und verzuckerten Klischees. Stattdessen entdeckt er ihn als Wahlverwandten: nämlich als radikalen Nonkonfromisten, der in der konsequenten Verfolgung der jeweiligen Formidee selbst vor dem Bizarren nicht zurückscheut.

Emotionale Kraft

Ähnlich frisch und unverstellt von Konventionen ist Guldas Zugang zu den französischen Impressionisten. Mit berückendem Klangsinn, aber schlank, transparent und, wenn nötig, mit jazzigem Drive spielt der junge Gulda Debussy. Frappierend etwa seine entschlackte, wunderbar schwebende Interpretation des berühmten "Clair de lune" – nichts von dem parfümierten Schmachten, mit dem diesem arg strapazierten Stück so oft Unrecht getan wird. Als einziges Solokonzert, im Zusammenspiel mit dem RIAS-Symphonie-Orchester unter dem beherzt zupackenden Dirigenten Igor Markevitch, ist Mozarts c-Moll-Konzert in der Box vertreten: ein Lehrstück über die emotionale Kraft, die im konsequenten Vermeiden jeglicher Sentimentalität stecken kann. Alles in allem eine Fundgrube für Gulda-Fans und ein Muss für Klavier-Enthusiasten.

Wochen-Kurier | 29. Jahrgang, Nr. 37 | Michael Karrass | 16. September 2009

Das Bild, das die musikalische Öffentlichkeit von Friedrich GuldaMehr lesen

DeutschlandRadio Kultur - Radiofeuilleton | CD der Woche, 14.09.2009 | Oliver Schwesig | 14. September 2009

In einem Gemeinschaftsprojekt zwischen dem Label "audite" und Deutschlandradio Kultur werden seit Jahren einmalige Aufnahmen aus den RIAS-Archiven aufMehr lesen

Die jüngste Produktion dieser Reihe "The Early RIAS-Recordings" enthält bisher unveröffentlichte Aufnahmen von Friedrich Gulda, die zwischen 1950 und 1959 entstanden. Die Einspielungen von Beethoven, Debussy, Ravel und Chopin zeigen den jungen Pianisten an der Schwelle zu internationalem Ruhm.

Die Meinung unserer Musikkritiker:

Eine repräsentative Auswahl bisher unveröffentlichter Aufnahmen, die aber bereits alle Namen enthält, die für Guldas späteres Repertoire bedeutend werden sollten: Mozart, Beethoven, Debussy, Ravel, Chopin. Herausragend insbesondere seine Interpretationen von Werken Beethovens. In dessen später A-Dur-Sonate op. 101 erleben wir den Jungstar als kühnen Stürmer und Dränger, der seine spätere Rolle als kompromissloser Musik-Rebell zwar noch nicht gefunden hat, dessen heftiges "Renitenz-Potential" hier aber bereits deutlich anklingt.

(Wilfried Bestehorn)

In diesen frühen Tondokumenten aus den 50er Jahren ist Guldas typisches intensives, rhythmisch-geschärftes Spiel bereits voll entwickelt. Vor allem in Chopins Préludes op. 28 und Debussys "Suite Bergamasque" wird deutlich: alles atmet, alles fließt, alles entwickelt sich logisch aus dem Notentext heraus: erstaunlich bei einem kaum 20-jährigen Pianisten, erstaunlich auch, dass diese Aufnahmen nach knapp 60 Jahren nichts von ihrer Frische eingebüßt haben.

WDR 3 | WDR 3 TonArt; Mittwoch, 09.09.09 um 15:05 Uhr | Christoph Vratz | 9. September 2009

Er hat die Musikwelt gespalten wie kaum ein Anderer – und er hat sich anMehr lesen

Radio Stephansdom | CD des Tages, 04.09.2009 | 4. September 2009

Aufnahmen, die zwischen 1950 und 1959 entstanden. Glasklar, "gespitzterMehr lesen

Piano News | September/Oktober 2009, 5/2009 | Carsten Dürer | 1. September 2009 Friedrich Guldas frühe RIAS-Aufnahmen

Er war vieles in einer Person: Der Pianist Friedrich Gulda (1930-2000) warMehr lesen

Neue Musikzeitung | 9/2009 | Andreas Kolb | 1. September 2009 Konzertprogramm im Wandel

1978 veröffentlichte Friedrich Gulda auf fünf Langspielplatten seinMehr lesen

www.amazon.de | 3. Februar 2010 | Quelle: https://www.amaz... Eine Offenbarung

Die 4 CDs, aufgenommen 1950, 1953 und 1959, enthalten Werke ganz unterschiedlicher Kompositionen und Stilrichtungen, von Mozart über Beethoven,Mehr lesen