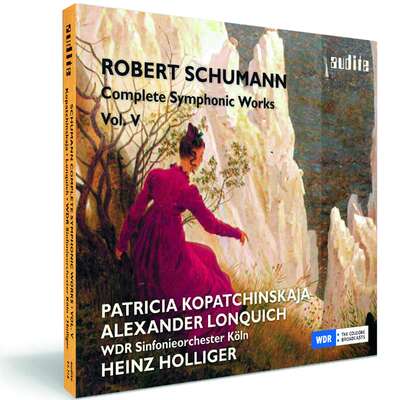

“Holliger’s profound empathy for Schumann shines through these outstanding performances which sustain a miraculous transparency of orchestral texture without sacrificing expressive intensity.” (BBC Music Magazine) „Selten hatte man das Gefühl, ein Dirigent könnte einem Komponisten so in den Kopf schauen wie Heinz Holliger Robert Schumann.” (Fono Forum)mehr

“Holliger’s profound empathy for Schumann shines through these outstanding performances which sustain a miraculous transparency of orchestral texture without sacrificing expressive intensity.” (BBC Music Magazine) „Selten hatte man das Gefühl, ein Dirigent könnte einem Komponisten so in den Kopf schauen wie Heinz Holliger Robert Schumann.” (Fono Forum)

Titelliste

Details

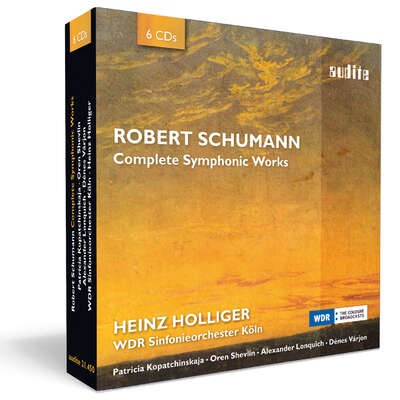

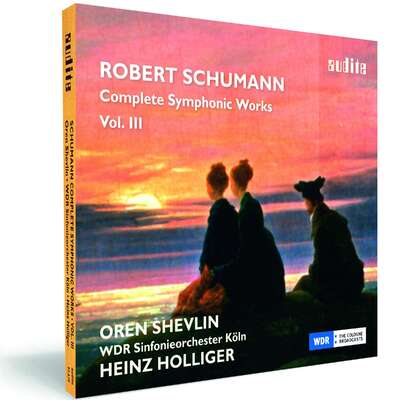

| Robert Schumann: Complete Symphonic Works | |

| Artikelnummer: | 21.450 |

|---|---|

| EAN-Code: | 4022143214508 |

| Preisgruppe: | BCG |

| Veröffentlichungsdatum: | 2. November 2018 |

| Spielzeit: | 398 min. |

Zusatzmaterial

Informationen

"[...] one of the most attractive collections of this music." (Gramophone)

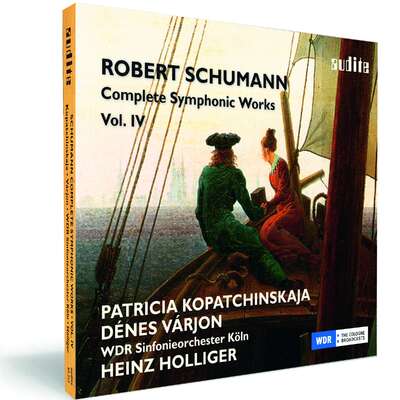

Die Edition enthält neben den Sinfonien Nr. 1-4 die Sinfonie d-Moll in der Originalfassung und die „Zwickauer-Symphonie" in g-Moll. Hinzu kommen Ouvertüre, Scherzo & Finale, die Ouvertüren (Manfred / Hermann und Dorothea / Genoveva / Die Braut von Messina / Julius Cäsar / Szenen aus Goethes Faust) und alle Solowerke mit Orchester: Das Violinkonzert und die Fantasie mit Orchester (Patricia Kopatchinskaja), das Cellokonzert (Oren Shevlin), das Klavierkonzert (Dénes Várjon), die beiden Konzertstücke für Klavier (Alexander Lonquich) und das Konzertstück für vier Hörner (Horngruppe des WDR Sinfonieorchesters).

Diese Werkauswahl macht die Edition zu einer der umfassendsten Ausgaben der sinfonischen Werke Schumanns.

Der Schumann-Spezialist Heinz Holliger widerlegt mit dieser Edition eindrucksvoll das Vorurteil des für großes Orchester unglücklich instrumentierenden Komponisten Robert Schumann.

Alle Aufnahmen sind weiterhin auch als Einzelausgaben im CD-Format erhältlich.

Besprechungen

Scherzo | 01.05.2019 | Félix de Azúa | 1. Mai 2019

Este cofre es imprescindible para seguidores serios, investigadores o meros aficionados a la música de Schumann. La primera y primordial razón es la espléndida presencia de la orquesta de Colonia, cuya plenitud sonora, disciplina y libertad son sensacionales. Mehr lesen

Stuttgarter Zeitung | 22. Januar 2019 | Hans Jörg Wangner | 22. Januar 2019 | Quelle: https://www.stut...

Der Tondichter spricht

Heinz Holligers beispielhafte Schumann-Aufnahmen sind jetzt in einer Box erschienen

Am 21. Mai wird Heinz Holliger 80 Jahre alt. Für die Freunde und Fans desMehr lesen

La Libre Belgique | 12.12.2018 | N.B. | 12. Dezember 2018 Coffret inattendu que celui-ci

Et aussi parce que le Suisse, dirigeant un orchestre de qualité sans être exceptionnel (celui de laWDR de Cologne) arrive à de très beaux résultats de transparence et d’expressivité.Mehr lesen

Stretto – Magazine voor kunst, geschiedenis en muziek | December 5, 2018 | Michel Dutrieue | 5. Dezember 2018 | Quelle: http://www.stret...

De beroemde, Zwitserse hoboïst, fluitist, componist en dirigent Heinz Holliger (°1939) onderscheidde zich vroeger reeds van andere hoboïsten doorMehr lesen

De Schumann-specialist Heinz Holliger bewijst hier met succes, in tegenstelling tot wat algemeen wordt aangenomen, de grote kunst van orkestratie en instrumentatie van Robert Schumann. De interpretaties van Heinz Holliger zijn gebaseerd op een levenslange studie van de muziek, het denken, de persoonlijkheid en het tragisch lot van Schumann. Het cliché van Schumann als zwakke orkestrator, wordt weerlegd door de opvallend luchtige en subtiel gestructureerde klank van Holligers doordachte uitvoeringen.

Als dirigent komt de veelzijdige muzikaliteit van Heinz Holliger naar voor als een ervaren Schumann-expert, die met het uitstekend WDR-orkest, alles neerzet waarnaar de componist streefde. Het is prachtige (orkest)muziek van een levendige en gedreven, romantische geest, zorgvuldig doordacht. De complete editie van de symfonische werken van Robert Schumann met het WDR Symfonieorkest Keulen, bevat naast de vier Symfonieën, ook de Symfonie in re klein (nr. 4) in de originele versie uit 1841, evenals de onbekende Symfonie in sol klein WoO 29, (“Jugendsinfonie” of “Zwickauer Sinfonie”) uit 1833. Daarnaast zijn opgenomen het Celloconcerto op. 129 met Oren Shevlin (°1969) als solist, het helaas nog steeds onbekend Vioolconcerto in d, WoO 1 met violiste Patricia Kopatchinskaja (°1977), en het Pianoconcerto met Dénes Várjon (°1968) als solisten.

Daarnaast ontdekt u het Konzertstück voor Piano & orkest in d, op. 134 (1853) met als solist, Alexander Lonquich, het Konzert-Allegro mit Introduktion voor piano en orkest op. 134 (1853 ) door Patricia Kopatchinskaja, de Fantasie voor Viool en orkest, op. 131 (1853), Introduktion und Allegro appassionato – Konzertstück voor piano en orkest in G, op. 92 (1849) door Alexander Lonquich en het indrukwekkend Konzertstück voor vier hoorns & orkest, op. 86 (1849) met als solisten Paul van Zelm, Ludwig Rast, Rainer Jurkiewicz en Joachim Pöltl. Schitterend!

Deze selectie van werken creëert een van de meest uitgebreide en best uitgevoerde en opgenomen edities van Schumanns symfonische werken door een ware Schumann-specialist, Heinz Holliger. Niet te missen.

BRF 1 Radio

| Mittwoch, den 7. November 2018, Klassikzeit | Hans Reul | 7. November 2018 | Quelle: https://1.brf.be...

BROADCAST

Klassikzeit: WDR-Sinfonieorchester spielt Robert Schumann

Unter der Leitung von Heinz Holliger bringt das WDR-Sinfonieorchester beimMehr lesen

Correspondenz Robert Schumann Gesellschaft | Nr. 39 / Januar 2017 | Irmgard Knechtges-Obrecht | 1. Januar 2017

Die Musiker des WDR Sinfonieorchesters finden aufgrund des feinnervigen und auf Schumann spezialisierten Dirigats von Heinz Holliger für jedes Werk den entsprechenden Ton, was diese CD besonders farbenreich und vielseitig werden lässt. Mehr lesen

Correspondenz Robert Schumann Gesellschaft | Nr. 39 / Januar 2017 | Gerd Nauhaus | 1. Januar 2017

Wir erleben ein homogenes Quartett, aus dem sich die halsbrecherisch schwierige 1. Hornpartie bei Bedarf heraushebt, das aber in lyrischen wie dramatischen Partien mühelos seinen Mann steht, so dass eine der mitreißendsten Darbietungen des Konzertstücks entsteht, die der heutige Musikmarkt zu bieten hat.Mehr lesen

Stereo | 1/2017 Januar | Arnt Cobbers | 1. Januar 2017 Kritiker-Umfrage: Die zehn besten CDs 2016

Arndt Cobbers: 2. Schumann, Sämtliche Sinfonische Werke Vol. 5; Kopatchinskaja, Lonquich, WDR Sinfonieorchester, Holliger (Audite): Das alsMehr lesen

Correspondenz Robert Schumann Gesellschaft | Nr. 39 / Januar 2017 | Michael Struck | 1. Januar 2017

[Patricia Kopatchinskaja] zwingt uns zum Zuhören. Kein Ton lässt sie kalt. Sie liebt die Extreme, lebt sie geigerisch aus – und wirkt dann mitunter wie eine "Nina Hagen des klassischen Violinspiels".Mehr lesen

Rheinische Post | 28. Dezember 2016 | Volker Hagedorn | 28. Dezember 2016 | Quelle: http://www.rp-on...

Die Geister, die Robert Schumann rief

Sein großartiges Violinkonzert wird derzeit von vielen Geigern entdeckt. Ein Vergleich fördert spannende Entdeckungen zutage

"Robert hat ein höchst interessantes Violinkonzert beendet, er spielte es mir ein wenig vor, doch wage ich mich darüber nicht auszusprechen, als bisMehr lesen

Ach, hätten ihm Geisterstimmen doch noch zugeflüstert, dass 150 Jahre später fast alle großen Geiger sein Stück spielen würden! Vorläufige Krönung: drei der derzeit profiliertesten Geigerinnen. Als erste legte Isabelle Faust vor einem Jahr ihre Aufnahme mit dem Freiburger Barockorchester vor, es folgte Patricia Kopatchinskaja mit dem WDR-Sinfonieorchester, und nun ist auch Carolin Widmanns Aufnahme mit dem Chamber Orchestra of Europe (COE) zu haben. Die Musikerinnen, alle zur Generation der frühen 1970er zählend, haben endgültig jene Stufe der Rezeption gezündet, auf der es nicht mehr um eine umstrittene Rarität geht.

Denn dieses Werk gehört zum Großartigsten, was Schumann für sinfonische Besetzung geschrieben hat. Ein neuer Ton ist da zu hören, im ersten d-Moll-Satz blockhaft Archaisches in expressive Rückblicke drängend, im zweiten Satz subtilste Rhythmik. Mit dem Finale indes hatte schon Clara ein Problem, und Joachim fand es "entsetzlich schwer für die Geige". War das ein Grund, die Partitur zu verstecken? Auf Claras Wunsch kam sie nicht in die Gesamtausgabe. Joachim, Besitzer des Autographs, verwies dazu 1889 auf "eine gewisse Ermattung, welcher geistige Energie noch etwas abzuringen sich bemüht".

Auf ihn und Clara geht die zählebige "ideé fixe" zurück, Schumanns Spätwerk zeige Züge geistiger Zerrüttung. Joachims Sohn verkaufte das Autograf der Preußischen Staatsbibliothek 1907 mit der Auflage, das Konzert 100 Jahre lang nicht zu publizieren, Schumanns Tochter Eugenie wehrte sich noch als Greisin gegen die Publikation, die 1937 nur möglich wurde, weil die Nazis einen "arischen" Ersatz für das Violinkonzert von Felix Mendelssohn brauchten. Dem Nationalgeiger Georg Kulenkampff war die Partie zu schwer (anders als zur selben Zeit dem jungen Yehudi Menuhin in den USA), und kein Geringerer als Paul Hindemith gab sich dazu her, von 523 Takten der Sologeige mehr als die Hälfte umzuschreiben, sie hochzuoktavieren, einfacher spielbar und dabei "brillanter" zu machen – was faule Routiniers gern "dankbar" nennen.

Auch diese "Uraufführung" vom 26. November 1937 kann man nun wieder hören, ohne die einleitenden Worte von Propagandaminister Goebbels zu Beginn dieser "Kraft durch Freude"-Veranstaltung in Berlin. Georg Kulenkampff hetzt durch den ersten Satz wie durch eine Zirkusnummer, den letzten Satz hat er von Schumanns Metronomzahl 63 auf 104 hochgedreht, und der langsame Satz versinkt zum Glück im spacigen Zirbeln der Interferenzen und Datenverluste, die sich beim Überspielen welker Wachsplatten auf Band ergaben. Obwohl auch Yehudi Menuhin das Werk wenig später in den USA spielte, hatte es nun einen braunen Schatten zusätzlich zum Zerrüttungsverdacht. Wirklich verlässliche Notenausgaben gibt erst seit knapp zehn Jahren.

Diese lange Geschichte ist wie weggeblasen, wenn das famose Chamber Orchestra of Europe dirigentenlos in den ersten Satz einsteigt, schneller als von Schumann gedacht, voller Sturm und Drang. Die leeren E-Saiten der Geigen werden bewusst expressiv, fast schmerzhaft eingesetzt, was die Nachdenklichkeit der Solistin um so deutlicher macht. Den halben Noten zwischen ihren Sechzehnteln sinnt Carolin Widmann wie mit weiten Blicken nach, während Kopatchinskaja diese Töne ankrallt, hinschmeißt, fast wütend, und Isabelle Faust lange und kurze Noten in Schönheit verbindet – nuancenreich, nicht oberflächlich.

Das Freiburger Barockorchester, von Pablo Heras-Casado geleitet, entwickelt dabei nicht so viel Sog wie das Chamber Orchestra of Europe, lässt aber Registerwechsel, Farbkontraste deutlicher werden und ist trockener aufgenommen. Das größer besetzte WDR-Sinfonieorchester unter Heinz Holliger, als Autor ein kompetenter und subtiler Schumann-Versteher, wirkt dagegen etwas gedeckelt und unterspannt – in kuriosem Kontrast zur Geigerin Patricia Kopatchinskaja, der ihr Eigensinn öfter wichtiger ist als das poetische Potenzial der Musik. Krachende Tonbildung im Forte und Pianissimi an der Grenze der Hörbarkeit können durchaus nerven, auch wenn man ihr alle Aktionen glaubt und sich oft fragt, was ihr wohl als nächstes einfällt. Sie gibt ein bisschen das "bad girl".

Die Überraschungen ihrer Kolleginnen liegen in dem, was sie bei Schumann entdecken. Während Isabelle Faust ihn behutsam mit der weiten Welt verbindet, geht Carolin Widmann ins Innere und beschert uns im langsamen Satz die zärtlichsten Töne, unfassbar intim. Ihre schlichten leisen Synkopen in Takt 13 und 14 wagt man kaum ein zweites Mal zu hören, so etwas Unwiederbringliches haben sie. Dabei hilft freilich eine Aussteuerung, die die Solovioline auch bei leisesten Tönen unterstützt, während Isabelle Faust realistischer aufgenommen wurde, tiefer im Geflecht der umgebenden Töne. Genau das hat man Schumann – im bornierten Vergleich mit Genrestandards – vorgeworfen: Sein Solopart bewege sich zu oft im Schatten tieferer Lagen.

Vielleicht nimmt sich da einfach ein Subjekt zurück? Im Finale gilt das allerdings auch fürs Genie. Vielleicht war es Zeitdruck, der Schumann hier auf die "Images der Polenromantik" (so der Musikwissenschaftler Reinhard Kapp) vertrauen ließ: Eine gigantische Polonaise tritt auf der Stelle, Holzbläser verbreiten schauerlichen sächsischen Humor und die Geige spinnt fingerbrecherische Girlanden. Soll man das einfach schnell hinter sich bringen? Widmann und Kopatchinskaja drehen das Tempo auf 80 hoch, nur Faust lässt sich (fast) auf Roberts Angabe ein, und prompt scheint die Violine doch etwas zu sagen. Nur was? Rätsel hinter einer lächelnden Maske: Wir sollten nicht glauben, ihn jetzt zu kennen.

Das Orchester | 11/2016 | Jörg Loskill | 1. November 2016 | Quelle: http://www.dasor...

Der vielseitige Musiker Heinz Holliger ist als Dirigent ein kenntnisreicher Schumann-Exeget, der zusammen mit dem Maßstäbe setzenden WDR-Orchester alles zum Leuchten, Glühen und Brillieren bringt, was der Komponist anstrebte: einfach schöne Musik aus dem Geist der pulsierenden und aktuellen Romantik, ungebrochen, aber nachhaltig reflektiert.Mehr lesen

Die Zeit | Nr. 43 vom 13. Oktober 2016 | Volker Hagedorn | 13. Oktober 2016

Roberts Rächerinnen

Faust, Kopatchinskaja und Widman: Drei profilierte Geigerinnen haben Schumanns Violinkonzert eingespielt

Wie gewohnt gibt die Moldawierin ein bisschen das bad girl.Mehr lesen

Fanfare | October 2016 | Peter Burwasser | 1. Oktober 2016

This is the sixth and final volume of Audite’s survey of the complete symphonic works of Robert Schumann. As is often the case with suchMehr lesen

While there are no revelations in this program, the music is generally of high quality, even though it comes from the end of Schumann’s career, perhaps something of a rejoinder to the “truism” that Schumann’s abilities and imagination had eroded somewhat at this point. The problem for the listener, at least this one, is that the blustery nature of this dramatic music becomes a bit wearisome by the end of a complete listening. In hindsight, it may have made more sense to have included these dramatic overtures in more varied programs of symphonies and concertos, as is usually the practice in presenting such work. The exception is the early attempt at symphonic writing by a 21-year-old Schumann, the incomplete Symphony in G-Minor, named for the city it was premiered in, Zwickau. It is replete with lovely writing, with the composer’s signature firmly in place.

The complete set of Schumann orchestral music by these forces is certainly a success by almost any measure. I would offer one caveat, and that is that the WDR SO, while excellent and a great pleasure to hear, lacks the ultimate degree of polish and finesse of the top-tier orchestras of the world. But I’m not sure how much that matters in this material, given that a certain degree of lustiness, if anything, enhances the expressiveness of the music.

Frankfurter Allgemeine Zeitung | Montag, 19. September 2016 Nr. 219 | Jan Brachmann | 19. September 2016

Redet diese Musik, träumt sie?

Zwei Editionen mit den Konzerten von Robert Schumann wetteifern um die Deutung – auf hohem Niveau

Holliger und Kopatchinskaja machen im Violinkonzert auch Schumanns Zerrissenheit hörbar. Anschwellend, ausbrechend, versinkend entfaltet sich das erste Orchestertutti. In Kopatchinskajas erst dünnem, dann schnell und scharf akzentuiertem Geigenton liegen Wachheit, Reizbarkeit, bis jäh die Spannkraft erlahmt, die Sehnsucht nach Rückzug spürbar wird – und die Musik implodiert. Gespenstisch doppelgesichtig fallen Selbstbehauptung und seelische Ermüdung auseinander. Im Souveränitätsverlust treten Seiten des Menschlichen zutage, aus denen Kunst eine eigene Dringlichkeit gewinnt. Holliger hat das erkannt – und zugelassen.Mehr lesen

American Record Guide | September / October 2016 | Stephen Wright | 1. September 2016 | Quelle: http://www.ameri...

This is Volume 6 of Audite’s Complete Symphonic Works edition and contains Schumann’s earliest and latest pieces for orchestra, including all hisMehr lesen

Beethoven’s influence is also obvious in the only non-overture here, the unfinished Zwickau Symphony of 1833; this is Schumann’s third and final revision of the first movement, so it lacks the slow intro of John Gardiner’s 1998 recording (DG 457591). Gardiner’s orchestra has 40 strings where Holliger’s has 60, plus Holliger’s accents are tempered and his pace relaxed, so I heard for the first time the influence of Louis Spohr—another hero of the young Schumann—in the wilting chromaticism of the s tring figures.

Before the two-movement symphony, Holliger raises the curtain on the concert with the mature sonata-form Manfred Overture. In it we hear Holliger’s approach to all the overtures: warm, genial, and flowing. He lets the dramatic tension build up slowly, free of histrionics, with subtle orchestral flexibility to broaden tempos for grand climaxes and lyrical passages. The violins are split left and right as they were in Schumann’s time and they play cleanly, without vibrato, and this clarifies Schumann’s allegedly thick and clumsy orchestrations. There’s no mention anywhere of period instruments or gut strings, so I assume they’re modern, but at 60 strong they don’t sound shrill, nor do they indulge any supposed historic practice like swelling on long notes.

The sound quality matches interpretation: warm, full, and detailed, especially the surround-sound recording, right now available only as a download from Audite’s website (mentioned on the back of the digipak). The improvement in three-dimensional depth and presence is unmistakable in the five overtures recorded in 2010 but subtle in the symphony and Manfred recorded in 2015. Considering the high quality of both performance and surround-sound recording, I hope Audite issues a boxed set of this complete series on SACD (or Blu-Ray).

The booklet is informative, recounting the circumstances of each piece’s composition. This is an attractive and rewarding survey of Schumann’s overtures and makes me want to hear the other volumes in the series.

Das Orchester | 09/2016 | Thomas Bopp | 1. September 2016 | Quelle: http://www.dasor...

Zur Aufnahme mit Isabelle Faust und dem Freiburger Barockorchester haben nun auch Heinz Holliger und seine Solistin Patricia Kopatchinskaja im Rahmen der Gesamtveröffentlichung aller Orchesterwerke Schumanns mit dem WDR Sinfonieorchester Köln ihre Sicht auf das Violinkonzert niedergelegt. Und die dürfte Schumanns Vorstellungen vielleicht sogar noch um einiges näher kommen, als dies Isabelle Faust und den Freiburgern gelungen war.Mehr lesen

Spiegel online

| Sonntag, 21.08.2016 | Werner Theurich | 21. August 2016 | Quelle: http://www.spieg...

Violinkonzerte: Schumanns spätes Sorgenkind

Für die Violine gibt es beliebtere Konzerte als das von Robert Schumann. Carolin Widmann nahm sich das als spröde verschriene Werk vor. Bei ihr klingt es ganz anders als bei der Kollegin Kopatchinskaja

Man sieht Patricia Kopatchinskaja förmlich die Polonaise des dritten Satzes tanzen, weiß man doch aus ihren Konzerten, dass sie gerne mal den angestammten Solistenplatz verlässt und über die Bühne wandelt.<br /> <br /> Ihrem ausdrucksstarken und triumphierenden Spiel tut das Wilde natürlich keinen Abbruch, außerdem kann sie sich auf das sichere Geflecht der WDR-Truppe verlassen. Kopatchinskajas druckvoller Ansatz bekommt dem nun gar nicht so spröden Konzert ebenso ausgezeichnet wie Widmanns ganz andere Akzente. Klar ist auf jeden Fall: Schumanns lange geschmähtes Sorgenkind ist aller Sorgen ledig, wenn es in den richtigen Händen liegt.Mehr lesen

Ihrem ausdrucksstarken und triumphierenden Spiel tut das Wilde natürlich keinen Abbruch, außerdem kann sie sich auf das sichere Geflecht der WDR-Truppe verlassen. Kopatchinskajas druckvoller Ansatz bekommt dem nun gar nicht so spröden Konzert ebenso ausgezeichnet wie Widmanns ganz andere Akzente. Klar ist auf jeden Fall: Schumanns lange geschmähtes Sorgenkind ist aller Sorgen ledig, wenn es in den richtigen Händen liegt.

Fono Forum | August 2016 | Michael Kube | 1. August 2016 Empfehlung des Monats

Ein großer Zyklus kommt zum Abschluss. Nach den Sinfonien, Konzerten und Konzertstücken stehen in der letzten Folge der nahezu rundwegMehr lesen

Holliger aber sind anscheinend gerade diese Partituren ans Herz gewachsen – so ausgeglichen und wirklich als große Werke gespielt habe ich sie noch nicht gehört. Und sie zeigen Schumann im vollen Besitz seiner Fertigkeiten. Wer noch immer von angeblichen Problemen bei der Instrumentation spricht, sollte eher von Problemen der jeweiligen Interpretation sprechen (einer meiner persönlichen Favoriten ist und bleibt die Ouvertüre zu "Julius Cäsar"). Der für Schumann charakteristische, kompakte Klang kommt jedenfalls dem Sinfonieorchester des WDR entgegen, das schon fünf der Kompositionen 2010 eingespielt und sich den "Manfred" wie auch die frühe, unvollständig gebliebene Zwickauer Sinfonie in g-Moll nun für das Finale aufgespart hat – nicht als Supplement, sondern als geniale Vorschau auf das, was noch kommen sollte. So gespielt wirken die beiden Sätze denn auch nicht als philologische Kuriositäten, sondern künstlerisch berechtigt. Aus Holligers Nähe zu Schumann ist hier mit kühlem Kopf etwas Erstrangiges erwachsen.

Fanfare | August 2016 | Huntley Dent | 1. August 2016

The Schumann Violin Concerto, rejected in his lifetime by its dedicatee, Joseph Joachim, and suppressed after his death by his wife Clara and devotedMehr lesen

As a non-fan of the Violin Concerto, I can hardly credit that I am even more enthusiastic about this new release in Heinz Holliger’s ongoing Schumann orchestral cycle, of which this is Volume 4, with the extraordinary violinist Patricia Kopatchinskaja as soloist. In its daring departures from convention their reading surpasses Faust’s in fascination. To begin with, Kopatchinskaja, who was born in the former Soviet republic of Moldavia in 1977, has assumed the mantle of the late Lydia Mordkovitch for fierceness of attack and courageous nonconformity. Her timbre here is almost never consistent within a phrase or even beautiful. The tone whistles, whines, and scrapes as often as it sings, all in service of an interpretation that takes not a single note for granted. I associate this kind of keenly felt violin playing with Leila Josefowicz and more recently the young Norwegian phenom Vilde Frang. But Kopatchinskaja is the only violinist who has the ferocity to frighten me—I found her extreme interpretation of the Prokofiev Violin Concerto No. 2 and the Stravinsky Violin Concerto with Vladimir Jurowski from 2013 (Naïve) almost too unsettling to listen to. But it and her other releases, especially a disc of violin concertos by Eötvös, Bartók, and Ligeti on the same label, have been rapturously received, or at the very least caused heads to turn. The same is certainly true here.

The Schumann Piano Concerto exists at the opposite end of universal love and admiration, which makes things difficult for a relative unknown like Hungarian pianist Dénes Várjon—he won’t be unknown to those who have heard his recordings on Naxos, ECM, Hyperion, Capriccio, and other labels (I seem to be out of the loop on this one). A graduate of the Liszt Academy in Budapest, where he now teaches, Várjon has recorded Holliger’s music under the composer, so I assume a close musical affinity. Here they collaborate to produce a reading of the A-Minor Concerto that I’d describe as streamlined but intense. Tempos and phrasing are not out of the ordinary. The total timing is about the same as for Jan Lisiecki’s recent DG recording (reviewed in Fanfare 39:5), but where Lisiecki is poetic to the point of being subdued, Várjon puts his technique on extrovert display. Short of Martha Argerich’s charismatic, rocket-fueled interpretations, this is one of the more engaging readings of the solo part that I’ve heard, even if the finale loses oomph after a while.

Heinz Holliger has focused his Schumann cycle on making us hear the music without prejudice and absent the traditional Schumann Romantic sound. His starkness in the Violin Concerto succeeds remarkably well, although the orchestral part in the Piano Concerto feels a little abrupt and dry at times. At 77 he’s very much a force to be reckoned with. Holliger’s transition from superstar oboist to composer and conductor has worked on all counts, although here he doesn’t make the WDR Symphony sound better than workmanlike. That hardly matters, nor does the good but not exceptional recorded sound. It’s Kopatchinskaja’s highly original playing that wins the day.

Fanfare | August 2016 | Jim Svejda | 1. August 2016

The fourth and fifth volumes of Audite’s Schumann series with Heinz Holliger and the West German Radio Symphony are in many ways the mostMehr lesen

The version of the Piano Concerto is all we’ve come to expect from this excellent series, including alert, rhythmically flexible playing from a first-class radio orchestra (people who play to microphones for a living), a conductor who knows his business in Schumann (a firm grasp of the long line, an ability to clarify the occasionally dense inner voicing, a total lack of fear when it comes to punching the telling accent, an uncanny knack for pointing out the previously overlooked—but deeply important—detail), together with superbly realistic recorded sound that nonetheless bathes everything in an early-Romantic glow. The young Hungarian pianist Dénes Várjon takes a wonderfully fresh and unaffected approach to this familiar music; while everything feels perfectly controlled, he bends the bar line in a way that recalls the great Schumann pianists of the past (Cortot and Rubinstein especially) but nothing feels willful or self-aggrandizing. If the finale lacks the head-long excitement of Fleisher, Janis, Richter, and others, then overall it’s an immensely satisfying outing that makes you want to hear some of the solo piano music from this source. (There’s already an excellent version of the violin sonatas with Carolin Widmann on ECM 1902 and an even finer recording of the cello music with Steven Isserlis on Hyperion 67661.)

Wild child Patricia Kopatchinskaja’s presence guarantees an immensely individual look at the problematic Violin Concerto, and, as usual, she doesn’t disappoint. From her first entrance, it’s a startlingly original interpretation, with a seemingly endless variety of tone color—insured by her endless types of vibrato—down to that chilling moment in the heart of the first movement where the line is so drained of life it sounds like someone keening at a funeral. (There are other moments where the sound is so intense at the lower range of audibility that you wonder if she heard of Leonard Bernstein’s extraordinary instruction to a string section: “Play triple piano, but use the kind of vibrato you use playing triple forte.”) Holliger adds as much point and thrust as he possibly can to the outer movements—especially the opening movement, which for once never seems to drag—and although the slow movement seems less a premature anticlimax than usual, things never quite add up (as they never quite have, at least on records).

Kopatchinskaja is just as committed and persuasive in the violin Fantasie, whose gypsy-like opening flourishes are a reminder that it was written for the Hungarian-born Joseph Joachim, who actually played the piece (he refused to touch the concerto). Like the late Concert Allegro with Introduction which Schumann began writing only three days after the Fantasie was finished, it’s a work whose thematic inspiration is pretty thin gruel, as is the working out of the basic material. Like Kopatchinskaja, pianist Alexander Lonquich does everything he can to invest his part with life and interest, though well before the Concert Allegro begins you realize why—after a certain point—the composer’s widow stopped playing it in public.

All concerned are on far firmer footing in the earlier Introduction and Allegro appassionato, written well before Schumann was beginning to lose his grip on things. Lonquich responds admirably to the work’s impetuosity and high romance, though not with quite the same magical fusion of freshness and knowing finesse Jan Lisiecki achieves in his recent recording with Antonio Pappano (DG 479 5327).

The orchestra’s horn section turns in a spectacular account of the op. 86 Konzertstück, which still gets recorded far more frequently than it’s actually performed, given that its often stratospheric writing for the first horn is an endless series of clams just waiting to happen. Holliger and the soloists’ colleagues give them rousing support, though the closing bars lack the visceral excitement of Gerard Schwarz and the Seattle Symphony’s madcap dash to the end (Naxos 8.572770).

Collectors of this fine series will have snatched up both installments by now; others can proceed with minimal caution, as anything Kopatchinskaja does these days is mandatory listening.

Gramophone | August 2016 | David Threasher | 1. August 2016

With this sixth and final volume in his series of the 'Complete Symphonic Works', Heinz Holliger mops up the remaining segment of Schumann'sMehr lesen

That makes Holliger's the most complete cycle of the orchestral works to have arrived in ages. Dausgaard's three single discs (BIS) took in all the symphonic works (including both versions of the Fourth Symphony) along with the six overtures, while Gardiner's triple-set, on period instruments, dispensed with the overtures but included the wonderful Konzertstück for four horns and orchestra. If and when Holliger's six full-price discs come out in a budget-price box, that'll make this easily one of the most attractive collections of this music.

For those less bothered about such notions of completeness, other attractions include Holliger's clear-sighted interpretations, revealed in sound that is focused without being over-analytical. Perhaps the youthful 'Zwickau' piece and the much later concert overtures can't boast the winning melodies that make the greatest of Schumann's works stand out but they display all the composer's motivic skills and his development of the Beethovenian model in his own Romantic language, and offer valuable alternative lights on his orchestral career.

www.peterhagmann.com

| 13. Juli 2016 | Peter Hagmann | 13. Juli 2016 | Quelle: http://www.peter...

Ein Fall für die ideale Diskothek

Die Orchestermusik Robert Schumanns in Aufnahmen mit dem Dirigenten Heinz Holliger

Auch jenseits dessen warten die Aufnahmen mit manch ungewohnter Erfahrung auf. Die vierte Sinfonie, d-moll, lässt sich in der gewohnten Version von 1851 wie in der kaum je gespielten Erstfassung von 1841 hören.Mehr lesen

www.limelightmagazine.com.au

| July 2016 | Philip Clark | 1. Juli 2016

Thinking-Man's Schumann

Holliger's scholarly perspective impresses in symphonic mop-up

No man or woman alive knows more about the inner-workings of Schumann's music than Holliger, [...] teases out those melodic and harmonic fingerprints about to blossom in his mature symphonies. His Manfred Overture reminds us of the daring instability of Schumann's harmony – a music that opens the door, and takes a peek, at some harmonic traits of 20th-century music. The final volume has a slight feeling of mopping up what was left; but Holliger's interpretive perspectives make it worthwhile.Mehr lesen

hifi & records | 3/2016 | Ludwig Flich | 1. Juli 2016

Nun ist Holligers Schumann-Projekt abgeschlossen, und die Qualität hat sich von CD zu CD noch gesteigert. [...] Wer nach mehr Selbstverständlichkeit im Klang sucht, dem rate ich, alternativ die Flac-Version (48/24; auch in Surround) von der Audite-Website herunterzuladen.Mehr lesen

BBC Music Magazine | July 2016 | Erik Levi | 1. Juli 2016

Patricia Kopatchinskaja is typically bold and provocative in Schumann's Violin Concerto. Largely eschewing the full-blooded sonorities favoured byMehr lesen

Heinz Holliger and the WDR Sinfonieorchester are responsive partners both in the Violin Concerto and its far less problematic counterpart for piano. This latter work is presented in a relatively straightforward manner by Dénes Várjon, who emphasises its playfulness and lightness of touch, especially in the slow movement and Finale.

Holliger is particularly good at bringing out light and shade in Schumann's orchestration and highlighting inner details. This clarity of texture is evident throughout the two Konzertstücke for piano Op. 92 and Op. 134, where Holliger matches Alexander Lonquich's muscular tone with powerfully driven orchestral tuttis. The Konzertstücke for four horns, magnificently executed by the orchestra's principals, also benefits from Holliger's insights, the irresistible exuberance of the outer movements contrasting with the mellifluous expressiveness achieved in the central Romanze. Less convincing is the Fantasie for violin and orchestra, composed in the same year as the Violin Concerto but less exalted. Kopatchinskaja shows considerable charismatic imagination in projecting the rustic features of the faster section, but makes a few slips of intonation.

The Strad | June 15, 2016 | Peter Quantrill | 15. Juni 2016 | Quelle: http://www.thest... Two of today’s leading violinists take on the challenge of Schumann’s Concerto

The more consistently inspired outer movements bring out her quixotic, mercurial best, and once past an awkward edit into the finale, Kopatchinskaja makes this gawky but charming polonaise smile in ways that elude most of the competitionMehr lesen

RBB Kulturradio | Do 09.06.2016 | Dirk Hühner | 9. Juni 2016

Robert Schumann ist für den Schweizer Oboisten, Komponisten und Dirigenten Heinz Holliger mehr als eine Passion. Seit seiner Jugend ist er geradezuMehr lesen

Die sechste und letzte Folge sämtlicher sinfonischer Werke von Schumann umfasst sechs Ouvertüren und die frühe so genannte "Zwickauer Sinfonie". Wie bei den vorangegangenen Teilen entfaltet sich auch hier eine fein abgestimmte Dramaturgie, die verschiedene Lebensphasen und Stoffe zu einem größeren Bild zusammenfügt. Schon in der vom 21-jährigen Schumann in mehreren Anläufen zu Papier gebrachten "Zwickauer Sinfonie" weht und zirkuliert ein unruhiger Geist. Die in den 1850er Jahren, und also als "spät" apostrophierten Ouvertüren lenken diesen Geist auf literarische Stoffe von Shakespeare, Goethe, Schiller und Lord Byron. Aufruhr herrscht auch hier, aber doch in dramatische Form gegossen.

Schnelle Umschwünge

Dass die Ouvertüren heute kaum noch im Konzertleben anzutreffen sind, ist ein Manko des weniger auf klassische Bildung als auf Effekt zielenden Konzertbetriebs. Zumindest hat Heinz Holliger mit diesen Aufnahmen alle Vorurteile gegenüber einer groben Orchestrierung oder Gedankenschwäche bei Schumann gründlich widerlegt. Die Marseillaise in der Ouvertüre zu Goethes "Herrmann und Dorothea" ist nicht der einzige revolutionäre Ton, der hier immer wieder anklingt. Das Obsessive von Schumanns notorischen Motivdrehungen und –windungen schlägt hier Funken. Dabei sind die Tempi nirgends übertrieben schnell. Holliger strafft vor allem die Dynamik, die schnelle Umschwünge vollführen kann, ohne Nebenstimmen zuzudecken. Das WDR Sinfonieorchester Köln hat sich hier einen überraschend hellen Schumann-Ton erarbeitet, der fast kammermusikalisch erscheint.

Wenn diese CD mit den Fanfarentönen der "Julius Caesar"-Ouvertüre zu Ende geht, ist damit auch ein Aufnahmezyklus vollendet, der noch lange Bestand haben wird als einsichtige und Einsichten verschaffende Schumann-Gesamtschau.

www.opusklassiek.nl | juni 2016 | Gerard Scheltens | 1. Juni 2016

Maar het "pièce de résistance" van deze cd is toch het Konzertstück voor vier hoorns, dat door de eigenaardige bezetting niet vaak wordt gespeeld. Maar wat een geweldig stuk ... wat een vrolijkheid... en wat een speelplezier... hier kom je helemaal van bij...Mehr lesen

Crescendo Magazine | Le 22 mai 2016 | Ayrton Desimpelaere | 22. Mai 2016 Fin d’une très belle intégrale Schumann par Heinz Holliger

La violoniste Patricia Kopatchinskaja offre quant à elle une lecture éclairée et déterminée. Sous la baguette attentive de Heinz Holliger, elle exploite toute l’étendue de ses capacités pour rendre sa lecture passionnante. Il suffira d’écouter le mouvement central pour saisir la douceur du timbre et la compréhension sans faille de l’architecture. Patricia Kopatchinskaja croit en chaque note et dégraisse magistralement cette œuvre trop souvent négligée.Mehr lesen

www.niusic.de

| 13.05.2016 | Konrad Bott | 13. Mai 2016 | Quelle: http://www.niusi...

Liebevolle Ausnüchterung

Wenig Schmelz, viel Energie – Heinz Holligers Schumann erfrischt und hält auf Trab

Wo Akzente gesetzt werden, wird auch die hartnäckigste Schnarchnase aus dem Bett geschubst. Jeder Takt macht neugierig auf den nächsten, jede Kantilene wirkt frisch und sportlich, ohne zu hasten. Dass Schumanns sinfonischen Werke nicht nur etwas für romantische Schwelger sind, hat Holliger mit dieser Aufnahme ein für allemal klargestellt.Mehr lesen

Infodad.com | May 12, 2016 | 12. Mai 2016 When soloists soar

Having long since proved himself a superior oboist, Heinz Holliger is nowMehr lesen

Gramophone | 03.05.2016 | David Threasher | 3. Mai 2016

Schumann’s Violin Concerto has one of the strangest histories of all great Romantic works. His last piece for orchestral forces, it was inspired byMehr lesen

This coincided with a particularly stressful period in Schumann’s personal and professional life, not least the fallout from his deficiencies as a conductor with the Düsseldorf Musikverein. He was plagued by illness; but work on music for Joachim—two sonatas, the Phantasie, Op 131, and the Concerto—invigorated him and he remarked often on his ability to concentrate diligently on the music for his young new fiddler friend.

Joachim never performed the concerto, though. With Schumann’s decline and suicide attempt, the violinist considered the work to be ‘morbid’ and the product of a failing mind; he wrote that it betrayed ‘a certain exhaustion, which attempts to wring out the last resources of spiritual energy’. This attitude evidently rubbed off on Clara and Brahms, who omitted it from the complete edition of Schumann’s works. Joachim retained the manuscript and bequeathed it to the Prussian State Library in Berlin upon his death in 1907, stating in his will that it should be neither played nor published until 1956, 100 years after Schumann’s death.

It was in 1933, however, that it came to light. This is where the story turns very peculiar. The violinist sisters Jelly d’Arányi and Adila Fachiri held a séance in which the shade of Schumann asked that they recover and perform a lost piece of his; then Joachim’s ghost handily popped up to mention that they might look in the Prussian State Library. A copy of the score was sent to Yehudi Menuhin, who pronounced it the ‘missing link’ in the violin literature between Beethoven and Brahms, and announced he would give its premiere in October 1937. D’Arányi claimed precedence on account of Schumann’s imprimatur (albeit from the other side), and the German State invoked their copyright on the work and demanded a German soloist have the honour. Georg Kulenkampff was eventually entrusted with the world premiere; Menuhin introduced it in the US and d’Arányi in the UK.

It’s long been considered a problematic work, owing partly to Joachim’s opinion of it, partly to some supposedly heavy scoring and partly to the awkward gait of the polonaise finale, which can too easily become a graveyard for dogged soloists. Nevertheless, it’s something of a rite of passage for recording violinists, and two of the finest present it on new discs, as Patricia Kopatchinskaja goes head-to-head with Thomas Zehetmair. Kopatchinskaja (with the Cologne WDR SO under Heinz Holliger in Vol 4 of his series of Schumann’s ‘Complete Symphonic Works’) displays the full range of sounds she is able to draw from her instrument, spinning something almost hallucinatory in the slow movement. The tone employed by Zehetmair (directing the Orchestre de Chambre de Paris) is more focused, more centred, as would appear to be his outlook on the work: all three movements are 40 seconds to a minute faster than Kopatchinskaja. Nevertheless, her concentration and imagination sustain the performance, and Holliger and his players follow her lead in creating some wondrous sounds, demonstrating yet again that Schumann’s orchestration isn’t as leaden as it’s often made out to be.

On first hearing, I wasn’t sure if I’d wish to revisit Kopatchinskaja’s disc in a hurry. But there’s something magnetic about her vision of the work, about the abandon with which she plays, never shunning an ugly tone when it’s called for. Zehetmair’s tidier, more dapper performance avoids such ugliness and makes choosing between the two an invidious choice. Holliger couples an energetic performance of the Piano Concerto with Dénes Várjon, incorporating in the first movement some features of the earlier Phantasie on which it was based, and which some might prefer to the self-conciously individual recent readings by Ingrid Fliter (reviewed on page 40) or Stephen Hough (Hyperion, 4/16). Zehetmair offers a lithe, spontaneous Spring Symphony and the fiddle Phantasie that Joachim did play.

Pat Kop also offers this latter work, on Vol 5 of Holliger’s series. Again, she takes a more spacious, more reactive approach than Zehetmair; elsewhere on the disc, Alexander Lonquich is similarly more inclined to let the music breathe in Schumann’s two single-movement concertante piano works than, say, the tauter Jan Lisiecki (DG, 1/16). The real draw here, though, is the Konzertstück for four horns and orchestra, in a performance that makes a truly joyful noise, even if it’s perhaps less sleek than Barenboim in Chicago or less steampunk than John Eliot Gardiner with a quartet of period piston horns.

These days, you’re as likely to find—on disc, at least—the Cello Concerto co-opted by violinists. Jean-Guihen Queyras returns it to the bass clef, though, completing the series of the three concertos and piano trios with Isabelle Faust, Alexander Melnikov and the Freiburg Baroque Orchestra under Pablo Heras-Casado. Queyras gives the best possible case for the concerto, making a virtue of the relative short-windedness of period instruments but exploiting their greater ensemble clarity. Where the gut strings really tell, though, is in the First Piano Trio—especially at those points at which Schumann asks for new sounds, such as in the first-movement development, where he tells the string players to play at the bridge for an eerie, glassy sound. I’ve enjoyed all the discs in this series without necessarily preferring them to certain older (modern-instrument) favourites. The combination of Queyras’s concerto and the wonderful, driven D minor Trio, though, leads me to suspect that this is the most persuasive of the three.

ClicMag | N° 38 Mai 2016 | Pascal Edeline | 1. Mai 2016

Une fois de plus, Holliger concilie l'aspect réfléchi, apollinien, de la lisibilité des lignes et l'aspect dionysiaque de la ferveur, de l'effusion lyrique émanant comme une voix unanime des solistes et de l'orchestre, mais sa direction solaire magnifiant le contraste et la clarté pourrait laisser de marbre les nostalgiques des timbres fondus, des legato sinueux, des élans remontant des profondeurs obscures, des tensions intériorisées, des paysages nimbés de mystère. Mehr lesen

MJ | MAY 2016 | Naoya Hirabayashi | 1. Mai 2016

Japanische Rezension siehe PDF!Mehr lesen

Die Bühne

| Nr. 5 Mai 2016 | 1. Mai 2016

Empfehlungen der BÜHNE-Redaktion: Sterne des Monats

CD des Monats: Schumann, Complete Symphonic Works Vol. IV (audite)

Derzeit erlebt Schumanns Violinkonzert eine wahre Renaissance. Nach Isabelle Faust und Pablo Heras-Casado (harmonia mundi) bricht nun eine weitere CDMehr lesen

Thüringen Kulturspiegel | Mai 2016 | Dr. Eberhard Kneipel | 1. Mai 2016

AIte Schönheit - neuer Glanz

Die Gesamtaufnahme von Robert Schumanns Orchesterwerken beim Edel-Label audite

Erster Anlauf, erstaunliche Experimente, imponierende Meisterwerke: Ein außergewöhnliches und an Entdeckungen reiches Hör-Erlebnis ist zu haben – auch dank audite!Mehr lesen

F. F. dabei | Nr. 9/2016 vom 30. April bis 13. Mai | 30. April 2016 Mediamarkt – F.F. sichtet Musik- und Literaturangebote

Die fünfte Folge der Reihe ergänzt die Solokonzerte mit den kompakten Konzertstücken des Komponisten. Patricia Kopatchinskaja und Alexander Lonquich setzen dabei ihre ganz eigene Handschrift in die Kompositionen.Mehr lesen

The Guardian | 2016/Apr/28 | Andrew Clements | 28. April 2016 Holliger makes Manfred crackle

Anyone who has followed Holliger’s series won’t be disappointed by this final instalment.Mehr lesen

Der neue Merker | 26. April 2016 | Dr. Ingobert Waltenberger | 26. April 2016

Alexander Lonquich am Flügel bringt genau jenen melancholisch-jubelnden Ton, jenes fantastische Fabulieren voller zarter Farben ein, „polarisierend zwischen Trotz und Melancholie auf der einen, Traum und Sehnsucht auf der anderen Seite.“ Heinz Holliger als Seele des Unterfangens ist ein idealer Dirigent und Begleiter, der sich dem Schumann‘schen Kosmos beeindruckend anverwandt hat.Mehr lesen

Kölner Stadtanzeiger | Freitag, 22. April 2016 | Markus Schwering | 22. April 2016

Kampf gegen den Taktstrich

WDR Sinfonieorchester Holliger beendet glänzend seine Totale des orchestralen Schumann

Schließlich gelingt es Holliger, wirkungsvoll ein altes Vorurteil zu dementieren: dasjenige vom unfähigen Orchestrator Schumann und seinem fett-opaken Instrumentalsatz. Der Dirigent orientiert sich bei seinen WDR-Aufnahmen an der historischen Aufführungspraxis: Er dramatisiert, belüftet, entschlackt den Klang, verschärft Akzente, reduziert das Streicher-Vibrato, lässt die Bläserstimmen plastisch heraustreten, verwendet überhaupt auf die Balance der Gruppen größte Sorgfalt. Das Ergebnis: Der reife Schumann klingt hier, auch ohne angezurrte Tempi, jugendlich frisch.Mehr lesen

http://theclassicalreviewer.blogspot.de | Wednesday, 13 April 2016 | Bruce Reader | 13. April 2016 A very fine Violin Concerto from Patricia Kopatchinskaja that will surely help this work to gain acceptance and a particularly musical performance of the Piano Concerto in A Minor from Dénes Várjon on Heinz Holliger’s fourth volume of his complete survey of the orchestral works of Schumann for Audite

This is a particularly musical performance lacking in any superficial show for virtuosity’s sake. They receive an excellent recording again from the Philharmonie, Koln and there are excellent booklet notes.Mehr lesen

CD Journal | APR. 2016 | 1. April 2016

Japanische Rezension siehe PDF!Mehr lesen

concerti - Das Konzert- und Opernmagazin | April 2016 | Dr. Eckhard Weber | 1. April 2016 Unfassbar

Holliger durchmisst mit dem vor Energie strotzenden WDR Sinfonieorchester eine unfassbare räumliche Tiefe – Kopatchinskaja lässt ihren Geigenton vielfach schillern, das alles in präziser Linienführung. Schumanns Klavierkonzert dagegen befreien Holliger und Pianist Denes Varjon entspannt und reflektiert von schwülstiger Romantik, verleihen ihm Dynamik und Licht. Wahre Referenzaufnahmen!Mehr lesen

hifi & records | 2/2016 | Uwe Steiner | 1. April 2016

Patricia Kopatchinskajas Seelenton, im Lyrischen an der Grenze zum Verstummen, offenbart die kaum verhohlene, doch nie ausgestellte Melancholie dieser demonstrativ unvirtuosen Abschiedsmusik. Denes Varjon legt eine genau ausgehörte Deutung des Klavierkonzerts vor, die gerade auch im Finale nicht über die rhythmische Struktur hinwegmusiziert.Mehr lesen

Musica | N° 275 - aprile 2016 | Giuseppe Rossi | 1. April 2016

Un rinnovato interesse per le opere orchestrali di Robert Schumann ha vistoMehr lesen

Fono Forum | April 2016 | Michael Kube | 1. April 2016

Nach fast anderthalb Jahren setzt das Label audite seinen Schumann-Zyklus mit einer Doppelfolge fort. Aufgrund der Besetzung und der Werke fraglos einMehr lesen

Wie so oft erweist sich alles nur als eine Frage der Interpretation – von der Verständigkeit gegenüber dem Notentext über das aufmerksame Zusammenwirken bis hin zur passgenauen Artikulation und das rechte Tempo. In diesem Sinne gelingt es Holliger und seinen Solisten mit den Konzertstücken für Klavier op. 92 und op. 134 (Alexander Lonquich) sowie der Violin-Fantasie op. 131 tatsächlich zu überzeugen: Man hört einen Komponisten, dem das virtuose Element eigentümlich fremd und doch so nah war, dem am Ende aber der poetische Gedanke mehr zählte als jede leere Phrase. Hier begegnen sich über mehr als 150 Jahre hinweg die Komponisten Schumann und Holliger auf ästhetischer Ebene – der Dirigent Holliger aber weiß, wie auch der rechte Tonfall in einer klanglich agilen, in nahezu jedem Moment die Aufmerksamkeit bannenden Aufnahme festzuhalten ist. Umso mehr muss der stark aufgeraute, bisweilen kantige Zugriff von Patricia Kopatchinskaja im Violinkonzert verstören, der nicht gerade vor wohliger Wärme sprüht; das kühle Solo des langsamen Satzes lehrt einen gar das Frösteln. Daneben vermag Dénes Várjon im delikat angegangenen Klavierkonzert mit seinem eher vorsichtigen, keineswegs griffigen Forte nicht vollständig zu überzeugen.

Record Geijutsu | APR. 2016 | 1. April 2016

Japanische Rezension siehe PDF!Mehr lesen

Record Geijutsu | APR. 2016 | 1. April 2016

Japanische Rezension siehe PDF!Mehr lesen

Stuttgarter Zeitung | 22.03.2016 | Dr. Uwe Schweikert | 22. März 2016

Eine Großtat für Robert Schumann

Heinz Holliger und das WDR Sinfonieorchester Köln nehmen das gesamte sinfonische Werk auf

Man sagt wohl nicht zu viel, wenn man diese CDs als die wichtigste Schumann-Einspielung seit langem rühmt. Sie beweist, dass es keines historischen Instrumentariums und auch keines Spezialistenensembles bedarf, um die Werke aus dem Geist der Zeit für heute aufs Neue zu verlebendigen.Mehr lesen

The Guardian | Thursday 17 March 2016 | Andrew Clements | 17. März 2016

Schumann: Konzertstücke; Fantasies

CD review – questing and luxuriant

The work for four horns stands out, if only for the novelty of its scoring, and Holliger’s performance – with a fabulously secure quartet of soloists – luxuriates in the sonorities it generates, while in the two works with piano, the soloist Alexander Lonquich finds moments of poetic beauty in the lyrical interludes. Mehr lesen

ClicMag | N° 36 - 03/2016 | Pascal Edeline | 1. März 2016

Patricia Kopatchinskaja takes the experimental qualities of the Violin Concerto, a late work, as a guiding principle for her individual interpretation, rising above clichéd Romanticist listening habits. In the Piano Concerto, Dénes Várjon also expresses a particular Romantic clarity, characterised by fresh sounds and fluid tempi.Mehr lesen

www.opusklassiek.nl | maart 2016 | Gerard Scheltens | 1. März 2016 | Quelle: https://www.opus...

het vioolconcert met de wervelende " Pat Kop" een waar feest.Mehr lesen

Audio | 03/2016 | Lothar Brandt | 1. März 2016

Bei seinem Violinkonzert, das Robert Schumann noch vor dem Fall in die geistige Umnachtung vollenden konnte, fühlen sich Geiger und KommentatorenMehr lesen

Musik & Theater | 03/04 März/April 2016 | Reinmar Wagner | 1. März 2016 Feuerwerk an Ideen

[...] wenn Patricia Kopatchinskaja mit dabei ist, dann erhält die Bezeichnung Fantasie erst ihre wahre Bedeutung: Ein Feuerwerk an Ideen – manche spektakulär, manche nur Nuancen – lebendig, rhythmisch aufsässig präsentiert oder in lässiger Nonchalance gibt dieser Musik improvisatorischen Charakter.Mehr lesen

BBC Radio 3 | Record Review - Saturday 27th February 2016 | Andrew McGregor | 27. Februar 2016

BROADCAST

Record Review

Sendebeleg siehe PDF!Mehr lesen

The Herald Scotland | Friday 26 February 2016 | Michael Tumelty | 26. Februar 2016

Moldovan-born violinist Patricia Kopatchinskaja plays the Violin Concerto with an elemental conviction I have not heard. Her attack is phenomenal and she obviously believes every note she is playing. In the melting slow movement she will break your heart;Mehr lesen

http://asiagolfonline.com | 26.02.2016 | 26. Februar 2016

Patricia Kopatchinskaja plays the Violin Concerto with an elemental conviction I have not heard. Her attack is phenomenal and she obviously believes every note she is playing. In the melting slow movement she will break your heartMehr lesen

www.ilcorrieremusicale.it | 13 febbraio 2016 | Stefano Cascioli | 23. Februar 2016

Prosegue l’integrale delle opere sinfoniche di Schumann che l’AuditeMehr lesen

Rondo | Nr. 936 // 16. - 22.04.2016 | Guido Fischer | 19. Februar 2016

Herb, mit ungeschöntem Zugriff, bis an die Grenze des Brutalen richtet Patricia Kopatchinskaja den Blick auf die klaffenden Wunden, die diese Partitur eben auch offenbart. Und der Finalsatz ist trotz des Sehnsuchtstons doch ein einziger Seelentaumel.Mehr lesen

Vorarlberger Nachrichten | 19. Februar 2016 | Fritz Jurmann | 19. Februar 2016 MusikTipps von Fritz Jurmann

[...] auch hier setzt [Kopatchinskaja] in [Schumanns] späten, oft verkannten Violinkonzert d-Moll mit vibratoarmem Spiel und leeren Saiten deutliche Akzente. Experimentelle Züge dienen der Künstlerin als Leitbild für ihre stark individuelle Lesart jenseits aller klischeehaft romantisierten Hörgewohnheiten. Desgleichen verfährt sie mit seiner Fantasie für Violine, die ihrer ungezügelten Spielweise besonders entgegenkommt.Mehr lesen

www.ilcorrieremusicale.it | 18 febbraio 2016 | Stefano Cascioli | 18. Februar 2016

Senza dubbio è un Cd piuttosto singolare, che, vista la proposta di brani ben poco conosciuti, ha i tratti delle incisioni “di riempimento” (necessarie in ogni integrale che si rispetti), ma non per questo è una proposta meno interessante, anzi gli accostamenti sono davvero suggestivi, e chiariscono ancor meglio alcune peculiarità del complesso pensiero schumanniano.Mehr lesen

www.pizzicato.lu | 11/02/2016 | Alain Steffen | 11. Februar 2016 Holligers moderner Schumann

Ich habe mit Heinz Holliger als Dirigent nicht selten meine Schwierigkeiten. Gerade im romantischen Repertoire ist er mir oft zu kühl und zuMehr lesen

Wie schon Isabelle Faust räumt auch Kopatchinskaya mit den Klischees auf und zeigt uns Schumanns Musik in einem sehr frischen und dynamischen Gewand. Holliger dirigiert erstaunlich musikantisch, verzichtet aber wie gewohnt auf zu starke romantische Exkurse. So stehen vor allem ein aktzentreiches und klares Musizieren im Vordergrund.

Mit dem gleichen Konzept geht Holliger auch das beliebte Klavierkonzert an. Genussvoll lässt er das hervorragend disponierte WDR Sinfonieorchester Köln aufspielen, sieht aber seinen Schumann auch hier durch eine strengere klassischere Brille. Was der Musik aber sehr gut tut. Dénes Varjon spielt das Konzert sehr virtuos und mit einer sehr deutlichen Artikulation. Ob man jetzt dieses eher unromantische Interpretationskonzept mag oder lieber die Werke in der klassischen Optik sieht sei einem jeden überlassen. Für mich jedenfalls kommt das Violinkonzert in der Interpretation Kopatchinskaya/Holliger sehr nahe an das Referenzniveau heran.

Vol V. präsentiert etwas weniger attraktive Werke. Hier sticht insbesondere das Konzertstück für vier Hörner ins Auge. Holliger und seine Solisten wollen von Jägerromantik nichts wissen und spielen das Stück äußerst präzise und klar. Der Wohlklang der Hörner ist zwar präsent, ist aber mehr das Resultat einer analytischen und architektonisch begründeten Interpretation als das einer rein atmosphärisch orientierten. Alexander Lonquich spielt die beiden Konzertstücke für Klavier und Orchester op. 92 & 114 mit schönem Ton und ausgewogenem Ausdruck, Kopatchinskaya ist in der Fantasie für Violine und Orchester wieder einmal überragend. Heinz Holliger kann diesen drei Werken deutlich weniger interessante Aspekte abgewinnen als dem Violinkonzert oder dem Klavierkonzert.

Heinz Holliger continues to explore Schumann’s symphonic works in a very clear and analytical way. The highlight of the CDs is the very fresh and vivid performance of the Violin Concerto.

NDR Kultur | 21. Januar 2016

BROADCAST

"Matinee"

Sendebeleg siehe PDF!Mehr lesen

classical ear | Friday August 15 | Colin Anderson | 15. August 2015 | Quelle: http://classical...

Dedicated playing and excellent sound complete this notable release; believe me, five stars are not enough.Mehr lesen

www.opusklassiek.nl | mei 2015 | Siebe Riedstra | 1. Mai 2015

De Zwitserse hoboïst, componist en dirigent Heinz Holliger heeft zich in al zijn disciplines intensief met het werk van Schumann beziggehouden. Als componist leidde dat tot verassende resultaten, getuige zijn Romancendres (hier besproken door Aart van der Wal). Als dirigent munt Holliger in de eerste plaats uit door een buitengewoon scherp en precies gehoor, tot op de Herz nauwkeurig. Zijn slagtechniek sluit niet naadloos aan op die precisie, en dat hoor je bijvoorbeeld in de wat rommelige start van de Eerste symfonie. Mehr lesen

American Record Guide | April 2015 | David W Moore | 1. April 2015

This is Volume 3 of Schumann’s complete Symphonic Works on Audite. <br /> These two works make a nice combination, since they share a formal structureMehr lesen

These two works make a nice combination, since they share a formal structure that connects the movements in a subtle and satisfying way. Both are in minor keys and share a depth of feeling that make them two favorites of mine.

These performances are not the grandest I have heard. Shevlin is a fine cellist, principal in this orchestra since 1998. He gives a friendly, sensitive reading of this great concerto. Holliger conducts that and the symphony with style, taking all the repeats in the symphony. I sometimes wish that both works were treated with a little more grandeur, but they are richly recorded.

These two works make a nice combination, since they share a formal structure

Schumann-Journal | Nr. 4 / Frühjahr 2015 | Jan Ritterstaedt | 1. April 2015

Die Folgen 2 und 3 der neuen Gesamteinspielung sämtlicher sinfonischer Werke Robert Schumanns setzt die mit der ersten CD begonnene Interpretationslinie konsequent fort. Hier entsteht eine Reihe von Aufnahmen, die einen sicherlich sehr individuellen, in gewisser Weise auch modernen, vor allem aber künstlerisch sehr wertvollen Beitrag zur Schumann- Diskografie leistet. Man darf jetzt schon auf das nächste Produkt dieser Serie gespannt sein!Mehr lesen

Fanfare | 26.03.2015 | Steven Kruger | 26. März 2015

I wish I could be more enthusiastic about these performances. But I’m afraid sympathy is in order—for the continuing tendency of German orchestrasMehr lesen

About a year ago, I had more favorable things to say about Heinz Holliger’s CD of the “Spring” Symphony and early version of the Fourth. He seemed to bring a joyous bounce to the fanfares in the young work, and his foreshortening of things went well with notions of impetuous ardor. Similarly, the early Fourth, whose holes in orchestration are the aural equivalent of Swiss cheese, benefitted from a tight and virtuosic zest, clipping virtually everything to its benefit. It sounded demoted to piano suite status—but brought off well. Small consolation for admirers of original versions….

The CD here records the 1850 revision and expansion of the score. Schumann’s reworking fleshes out all the gaps which existed earlier and encourages grand, blazing, and sweeping phrases. In the right performance, the work lands nearly within reach of the Brahms Second Symphony in terms of impact—27 years before the fact. But in the wrong hands?

The performance here is perversely scrawny and metallic on top, tubby on the bottom from an uninspired timpanist, and discombobulated beyond prediction. Every phrase is too short, in a sort of Baroque manner, except for the ones which should be short. Every syncopation seems to have its own syncopation. And worse, there is considerable energy, only it never soars. Such electricity as there is, is wasted on aggression. It is like being rabbit-punched by Handel.

One of the persistent and poorly supported ideas about the Mendelssohn/Schumann era is the notion that these composers only experienced small orchestras. Even if this were true, it wouldn’t mean composers were necessarily happy with the resources before them. Schumann and Mendelssohn were friends and participated in numerous music festivals together during the 1840s. I don’t imagine the early music purists like to be reminded that the orchestras were enormous. The premieres of Paulus and Elijah had orchestras of 176 and 172 musicians respectively. Berlioz managed to conduct the Fantastique at the Crystal Palace with 150 (and his score demands 250). I cannot quote similar chapter and verse about Schumann, but he was well aware that music was getting really “big” and probably had conducted his own symphonies with large orchestras.

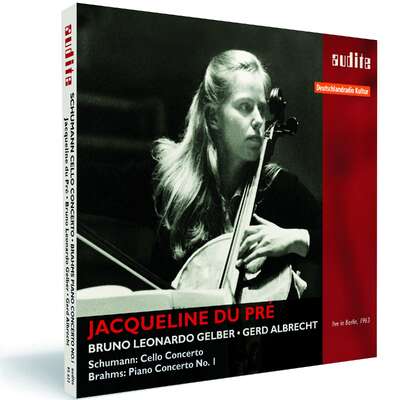

I shouldn’t fail to mention the cello concerto, the other late work included on this CD. It is always fascinating structurally, demonstrating how powerful an example the influence of Mendelssohn, in general and his violin concerto, in particular, had been. One could argue, though, that the themes are not so memorable as they should be, nor the textures sufficiently varied. Without the lively finale, the piece would languish away from the repertory. I refreshed my ears for this review with the Jacqueline du Pré performance and was struck by how alive, beautiful, and somehow sweepingly “upward” her phrasing manner always was. Oren Shevlin is the principal cellist of the Cologne orchestra and an accurate and musicianly player. But his manner is far too even. It doesn’t help that the orchestra avoids vibrato. This is the Schumann Concerto on Sominex.

I cannot really recommend the CD, despite good sound and scholarly notes. Schumann’s music is surely somewhere to be found between Handel’s Water Music and the Delius Cello Concerto. But Holliger’s HIP divining rod didn’t work.

Gramophone | March 2015 | Philip Clark | 17. März 2015

Music that grapples with demons and is never wholly at ease, even when wings bless the darkness with glimpses of light—when you’re RobertMehr lesen

The symphonic models are clear and we hear the ghostly spectre of Haydn, Mozart, Beethoven, Brahms and Mendelssohn—but no one has told Schumann’s material that it needs to conform, and the music cannot help but spill over any frame its composer attempts to place around it. The first movement of his Symphony No 1 reaches an apparent cathartic end-point as a solo flute line marked dolce reconciles grinding harmonic and structural inner tensions. Time to stop this madness. But then brass, percussion and trilling woodwinds unleash a stampeding burlesque march. Baleful chromatic inclines smudge the harmony, like Offenbach or Sousa turned on their dark side, and such instability derives from the restlessness of Schumann’s mind, you think, rather than being an overtly conceptual compositional strategy. The free jazz of the Second Symphony’s sostenuto assai prologue, C major credentials asserted by having the strings play anything but, as the brass sustain pure C major triads; in the Third Symphony, that extra movement that sneaks in before the finale, a cobwebby and gothic reimagining of the grounding contrapuntal principles of Renaissance music and Bach; and the audacious cyclic structure of the Fourth Symphony, each movement played attacca and dovetailing into the next. This music of demons and angels grapples also with angles—to take on structure, awkward punctuation, Schumann pushing form, his personal mission being to remould the symphony. And when the realisation dawns that Schumann composed the first version of what would become his Fourth Symphony in the same year as his First Symphony, eyes blink in astonishment. The natural order of things would be to presume that Schumann’s streamlined Fourth Symphony is a perfect distillation of the first three symphonies—but the pathway through Schumann’s symphonic journey is filled with unexpected and improbable twists and turns.

Deciding to record a cycle of the Schumann symphonies begs the question: what exactly should be recorded? And complementary but divergent ideas about the Schumann symphonies have been paraded as rarely before, with four major conductors during the past 18 months releasing four major cycles on disc. Sir Simon Rattle, with the Berlin Philharmonic, gives us four symphonies with the early 1841 version of the Fourth, while Yannick Nézet-Séguin (and the Chamber Orchestra of Europe) and Robin Ticciati (with the Scottish Chamber Orchestra) opt for Schumann’s 1851 revised version. But Heinz Holliger and the WDR Symphony Orchestra of Cologne—like Sir John Eliot Gardiner and his Orchestre Révolutionnaire et Romantique, whose trailblazing 1997 Schumann cycle was given the boxed-up DG reissue treatment last year—perceive Schumann’s symphonic evolution in seven stages. When Holliger completes his cycle during the next year and a half, Schumann’s early Symphony in G minor (the Zwickau Symphony) will take its place alongside the first three canonic symphonies, both versions of the Fourth, and the oftenoverlooked mini-me symphony Overture, Scherzo and Finale—Schumann’s compositional twists of fate put into historical context by a composer/conductor/oboist who has been obsessed with the composer’s enigma for more than 40 years.

I made Rattle’s cycle my Critics’ Choice album of the year in the December 2014 issue; I’ve also elevated Nézet-Séguin’s to an equivalent position in the past. Ticciati’s set has given me much pleasure too, and even more to think about. Nézet-Séguin and Ticciati deploy chamber-orchestra string sections, with Ticciati most explicitly evoking period-instrument practice. Rattle’s Berlin set carries its weightier orchestral ballast very elegantly, and his set became my portal back to Schumann after a longer period than I care to admit when my listening had been dominated by Beethoven, Brahms and Bruckner. Rattle’s opulent, rapacious approach—the climax of the First Symphony’s opening movement and the Trio in the Second Symphony’s Scherzo seemingly moving faster than time itself, while the Berlin strings float the slow movement towards heaven—represented the warmest welcome back possible to Schumann’s dream-built chimeric fantasy world, the heartfelt directness of his melodic fancy played out over structural chess moves. Ticciati’s sometimes manically driven, flintier orchestral sound can be unexpectedly austere; Nézet-Séguin’s cycle is the most unashamedly Romantic of the four, fevered-brow gesturing, rubato with attitude.

Despite their differences, though, the sets are unified by one underlying common denominator—none of them could have been recorded 30, or even 20, years ago. Over the phone from his home in Zurich, Heinz Holliger suppresses a laugh when I ask: why now? Why, suddenly, have maestros gone all Schumann crazy? ‘Well, I started conducting him 30 years ago, when too many conductors had problems with Schumann,’ he reflects. ‘He was never a problem for pianists or composers—Debussy and Berg held him in great esteem—but conductors realised that you cannot try to sight-read Schumann; if you do, the music is completely grey.’ And even 50 shades of grey would not be enough to express Schumann’s multiverse of colour? ‘He does not write out everything; he doesn’t tell you which voice is the principal and which accompanies; nor whether one instrument should have a diminuendo while the others crescendo. To make a Schumann symphony sound light and transparent, as he intended, takes a lot of rehearsal. Each player needs to know whether they’re playing part of only the harmony, or whether they are involved in the counterpoint. Schumann was a great writer of words too, and you need to understand how close the phrasing is to speech. But many conductors are not so interested in this background; they just play what they read.’

Holliger reminds me that Schumann never heard more than 12 first violins during his whole life and, in his view, the period-instrument movement has had a very positive effect on how conductors perceive appropriate orchestral weighting and internal balance. And when I talk to Sir Simon Rattle a few weeks earlier, he makes a characteristically smart analogy: ‘We think of Beethoven and Brahms as being the grizzled old lions of Austro-German symphonic tradition,’ he tells me, ‘but Schumann’s symphonies move like a panther. Beethoven plunges his feet forcefully through the ground; but Schumann’s feet sprint and never fully touch the floor.’

Rattle can’t quite explain why Schumann is suddenly so de rigueur, although sometimes, he says, mysterious forces collude to raise the collective consciousness around a particular composer. But the important thing for Rattle is that distinct and informed conductorly perspectives must all be celebrated. Ticciati’s way is not his way, but Rattle admires enormously how he tackles the 1851 revision of the Fourth Symphony: ‘Robin makes a clear case for how the revised version can retain the radical edge of the 1841 version. Still it sounds like a fireball and I take my hat off to him.’

Which Fourth Symphony? That’s the most fundamental decision any wannabe Schumann conductor must make. To programme the 1841 version is to agree with Brahms, who owned the autograph score and wrote: ‘It is a real pleasure to see anything so bright and spontaneous expressed with corresponding ease and grace.’ He found the revised version charmless and stodgy, and Rattle and Holliger concur with Brahms, and each other, that the first version is much preferable—although they choose to do notably different things with that information. ‘Schumann made the revised piece in a depressive state,’ Rattle says, ‘and Brahms was completely right about the relative merits of the two versions.’ Holliger adds that Schumann’s orchestra in Düsseldorf, which premiered the new version, was nowhere near as honed as the standard of playing he had become accustomed to in Leipzig, while Schumann himself ‘was heavier, and moved and spoke more slowly’. But the pertinent point for Holliger is that Schumann retained his high-velocity metronome marks. Rattle chooses to ignore the later rewrite—Holliger gives us both but attempts to play the 1851 version, as he says, ‘retaining the true spirit of the earlier version’.

Holliger reminds me that he met Rattle 40 years ago when the young conductor invited him to perform Richard Strauss’s Oboe Concerto with the Bournemouth Symphony Orchestra. And Rattle clearly remains in awe of Holliger’s status as a Schumann guru—‘Ask Heinz, when you speak to him, to tell you about the tempo relationships in the symphonies and about his extraordinary discovery in the fourth movement of the Rhenish Symphony.’ And I’m happy to take my cue from the Music Director of the Berlin Philharmonic.

On paper, and in the mind, Schumann’s Second Symphony registers as the most conventionally ‘symphonic’, its four movement groundplan—with a slow introduction breaking into an Allegro trot—putting you in mind of the first two Beethoven symphonies or of Haydn. And as I began to reacquaint myself with Schumann’s symphonic world, I pondered how a composition that felt instinctively unified melodically and motivically could also sound so disparate and varied, like each movement acting as a standalone character piece (not that you would necessarily want that). Holliger provides an answer.

‘The first and second movements,’ he tells me, ‘have the same metronome mark of crotchet=144, and the slow movement is nearly half; then the finale is in a very fast one-beat-per-bar, but still you feel like each bar matches the beat of the slow movement. The whole symphony is in one, like the conception of Mendelssohn’s Scottish Symphony.’ Holliger explains how the music is glued together throughout by a four-note cell, but I ask him to tell me about the music’s disunity. Am I right to hear each movement orbiting independently too, in a way that is uniquely Schumann? Holliger alludes to Bernd Alois Zimmermann, the composer of Die Soldaten, Photoptosis and Requiem für einen jungen Dichter, who died in 1970, and who was famous for pieces that made liberal use of collage and knitted together layers of borrowed material. ‘He was fascinated by the idea of Kugelgestalt—that time is like a ball, and all times of all centuries are focused in one single point. I think Schumann understood this too. You ask about the Second Symphony—well, the beginning could be like 17thcentury polyphony and then, suddenly, it looks 120 years or more into the future. You feel this composer knows the whole history of music.’

The Second Symphony’s Scherzo has something of the lightness of Mendelssohn’s A Midsummer Night’s Dream, Holliger explains as he tells me about those angels and demons, ‘but is relentless, a diabolic dance, in the mood of ETA Hoffmann’. And that shockingly abrupt change of mood, the solo flute overtaken by a brutal march as the first movement of the First Symphony reaches its climax, is another characteristic Schumann moment. ‘In the First Symphony the flute symbolises a butterfly which here is overwhelmed by very tragic music. Marches are a frightening thing. Send soldiers to kill, and you’re asking them to stop thinking about what they are doing. Trills in Schumann, like the woodwind trills you mention, often tremor and shiver like music with a high fever—this is not the Baroque idea of a trill as ornamentation.’

Holliger talks about the symbolism of instrumental identity in Schumann’s music. In Overture, Scherzo and Finale a choir of three trombones appear suddenly like a premonition of the role they will take in the fourth movement of the Rhenish. ‘When his brother Eduard was dying, Schumann woke up at three in the morning. He had been dreaming about three trombones, and later he learnt that his brother had died at 3am. Always in Schumann, three trombones is a message about death.’ I mention that Rattle urged me to ask him about this same movement. ‘Well, when I looked at the sketches, I realised that the tempo changes to double the speed two beats later than in the printed score—nobody ever does this, but the difference is essential.’

That Schumann had such specific ideas about orchestral colour and instrumental identity runs triumphantly contrary to that tired cliché about his orchestration being somehow inept and clumsy. In the September 2014 issue of Gramophone, Robin Ticciati revealed that, for him, the attraction of Schumann is precisely because the orchestration is so, as he put it, ‘crazy’. ‘It’s also so controlled, and the palette is extraordinary. And I think when you get to a Schumann score, the first reaction is not to go, “What is all that?” but “What does he want?” and “What’s important here?”’ Ticciati hears clues about how Schumann ought to sound orchestrally in how he ‘orchestrates’ his piano music; and in the booklet-notes accompanying his cycle, Yannick NézetSéguin discusses how the defined attack and decay of modern trumpets help balance the orchestration.

And so Schumann wins. The consensus, circa 2014/15, is leave well alone. ‘Schumann learnt lots about orchestration from Mendelssohn, the greatest orchestrator of his time,’ Holliger explains, ‘and he tried to have a very transparent sound in the orchestra. It’s not that very heavy “German potato soup” sound. I never change a single note in any of the symphonies.’ Rattle confirms that Schumann must be ‘light and singing, or the sound can be too brittle—the key word is sostenuto.’ The impulsive and spontaneous side of Schumann is also important to Rattle. ‘The last symphonic music Schumann wrote was the Rhenish,’ he says, ‘and the fourth movement feels like Schumann falling apart, then the finale is an attempt to cradle him in a warm embrace. And for that to work, you can’t micromanage too heavily.’ Music to Schumann’s ears, I suspect—a composer who clearly knew the value of spontaneity: ‘My symphonies would have reached Opus 100 if I had but written them down,’ he said. ‘Sometimes I am so full of music, and so overflowing with melody, that I find it simply impossible to write anything.’

Image Hifi | 2/2015 | Heinz Gelking | 1. Februar 2015 Hörenswertes

Oren Shevlin spielt das Cello-Konzert eher lyrisch und versteht sich als Primus inter pares. Das wird mal eine sehr empfehlenswerte Gesamtaufnahme.Mehr lesen

International Record Review | February 2015 | John Warrack | 1. Februar 2015

With this third volume completing Audite's cycle of Schumann's symphonic works, Heinz Holliger couples the Cello Concerto to the revised version ofMehr lesen

It is still not an easy work to perform, and Holliger does admirably here, not only in seeing to it that details of orchestration are made clear but that the virtually singlemovement form, cyclic in its use of repeated main material, works well. He is also entirely justified in being flexible with tempos. Not only is this in keeping with the approach to tempo defended by most mid-nineteenth century German composer-conductors, Weber and Wagner prime among them, with this symphony it can help to express the overall form more lucidly. The Romanze in particular is most beautifully played (though the violin solo is surprisingly reticent); but Holliger also keeps the orchestra well balanced and lively in the outer movements, or rather sections, of the work. At the same time, he successfully moves the music across from the brooding opening to the strong, affirmative ending. The Cello Concerto is a much more problematic piece, also difficult to bring off. Oren Shevlin does well with the many passages when the cello is bustling away rather unrewardingly against the orchestra; he is clearly relieved to reach the central Langsam, when Schumann is much more recognizably himself with a song-like movement in which his own melodic genius as well as the powers of the cello are more freely released.