Heinz Holliger’s interpretations draw on a lifetime’s study of the music, thought, personality and fate of Robert Schumann. The cliché of Schumann being a weak orchestrator is disproved by the feathery lilt and subtly structured sound of Holliger’s recordings.more

"Holliger's profound empathy for Schumann shines through these outstanding performances which sustain a miraculous transparency of orchestral texture without sacrificing expressive intensity." (BBC Music Magazine)

Details

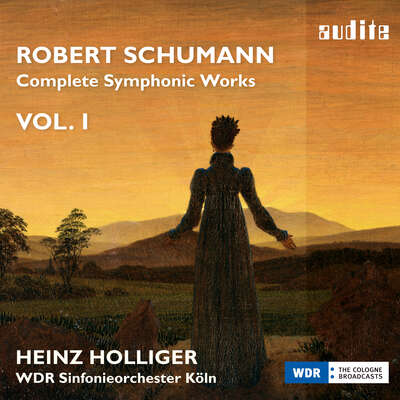

| Robert Schumann: Complete Symphonic Works, Vol. I | |

| article number: | 97.677 |

|---|---|

| EAN barcode: | 4022143976772 |

| price group: | BCA |

| release date: | 11. October 2013 |

| total time: | 71 min. |

Bonus Material

Informationen

This CD launches a complete series of recordings of Robert Schumann's orchestral works, performed by the WDR Symphony Orchestra under the baton of Heinz Holliger. The series will contain all the symphonies (including both versions of the Fourth) as well as all the overtures and concertos. Holliger's performances draw on a lifetime study of Schumann's music, thought, personality and fate. His approach imparts lightness and lucidity to these opulent scores through a hierarchical balance of parts, delicately gradated dynamics and invigorating tempos. The widespread image of this romantic composer as a weak orchestrator receives a refreshing and well-grounded correction. Volume 1 of the series presents the First Symphony in B-flat major (Op. 38), Overture, Scherzo and Finale (Op. 52) and the original 1841 version of the Fourth Symphony in D minor (Op. 120).

Reviews

Thüringen Kulturspiegel | Mai 2016 | Dr. Eberhard Kneipel | May 1, 2016

AIte Schönheit - neuer Glanz

Die Gesamtaufnahme von Robert Schumanns Orchesterwerken beim Edel-Label audite

Erster Anlauf, erstaunliche Experimente, imponierende Meisterwerke: Ein außergewöhnliches und an Entdeckungen reiches Hör-Erlebnis ist zu haben – auch dank audite!Mehr lesen

Stuttgarter Zeitung | 22.03.2016 | Dr. Uwe Schweikert | March 22, 2016

Eine Großtat für Robert Schumann

Heinz Holliger und das WDR Sinfonieorchester Köln nehmen das gesamte sinfonische Werk auf

Man sagt wohl nicht zu viel, wenn man diese CDs als die wichtigste Schumann-Einspielung seit langem rühmt. Sie beweist, dass es keines historischen Instrumentariums und auch keines Spezialistenensembles bedarf, um die Werke aus dem Geist der Zeit für heute aufs Neue zu verlebendigen.Mehr lesen

Gramophone | Fri 8th January 2016 | Philip Clark | January 8, 2016

Schumann's symphonies – building a fantasy world

Philip Clark explores why Simon Rattle, Heinz Holliger, Yannick Nézet-Séguin and Robin Ticciati are immersing themselves in Schumann's highly individual sound world

Music that grapples with demons and is never wholly at ease, even when wings bless the darkness with glimpses of light – when you’re RobertMehr lesen

The symphonic models are clear and we hear the ghostly spectre of Haydn, Mozart, Beethoven, Brahms and Mendelssohn – but no one has told Schumann’s material that it needs to conform, and the music cannot help but spill over any frame its composer attempts to place around it. The first movement of his Symphony No 1 reaches an apparent cathartic end-point as a solo flute line marked dolce reconciles grinding harmonic and structural inner tensions. Time to stop this madness. But then brass, percussion and trilling woodwinds unleash a stampeding burlesque march. Baleful chromatic inclines smudge the harmony, like Offenbach or Sousa turned on their dark side, and such instability derives from the restlessness of Schumann’s mind, you think, rather than being an overtly conceptual compositional strategy.

The free jazz of the Second Symphony’s sostenuto assai prologue, C major credentials asserted by having the strings play anything but, as the brass sustain pure C major triads; in the Third Symphony, that extra movement that sneaks in before the finale, a cobwebby and gothic reimagining of the grounding contrapuntal principles of Renaissance music and Bach; and the audacious cyclic structure of the Fourth Symphony, each movement played attacca and dovetailing into the next. This music of demons and angels grapples also with angles – to take on structure, awkward punctuation, Schumann pushing form, his personal mission being to remould the symphony. And when the realisation dawns that Schumann composed the first version of what would become his Fourth Symphony in the same year as his First Symphony, eyes blink in astonishment. The natural order of things would be to presume that Schumann’s streamlined Fourth Symphony is a perfect distillation of the first three symphonies – but the pathway through Schumann’s symphonic journey is filled with unexpected and improbable twists and turns.

Deciding to record a cycle of the Schumann symphonies begs the question: what exactly should be recorded? And complementary but divergent ideas about the Schumann symphonies have been paraded as rarely before, with four major conductors during the past 18 months releasing four major cycles on disc. Sir Simon Rattle, with the Berlin Philharmonic, gives us four symphonies with the early 1841 version of the Fourth, while Yannick Nézet-Séguin (and the Chamber Orchestra of Europe) and Robin Ticciati (with the Scottish Chamber Orchestra) opt for Schumann’s 1851 revised version. But Heinz Holliger and the WDR Symphony Orchestra of Cologne – like Sir John Eliot Gardiner and his Orchestre Révolutionnaire et Romantique, whose trailblazing 1997 Schumann cycle was given the boxed-up DG reissue treatment last year – perceive Schumann’s symphonic evolution in seven stages. When Holliger completes his cycle during the next year and a half, Schumann’s early Symphony in G minor (theZwickau Symphony) will take its place alongside the first three canonic symphonies, both versions of the Fourth, and the often-overlooked mini-me symphony Overture, Scherzo and Finale – Schumann’s compositional twists of fate put into historical context by a composer/conductor/oboist who has been obsessed with the composer’s enigma for more than 40 years.

I made Rattle’s cycle my Critics’ Choice album of the year in the December 2014 issue; I’ve also elevated Nézet-Séguin’s to an equivalent position in the past. Ticciati’s set has given me much pleasure too, and even more to think about. Nézet-Séguin and Ticciati deploy chamber-orchestra string sections, with Ticciati most explicitly evoking period-instrument practice. Rattle’s Berlin set carries its weightier orchestral ballast very elegantly, and his set became my portal back to Schumann after a longer period than I care to admit when my listening had been dominated by Beethoven, Brahms and Bruckner. Rattle’s opulent, rapacious approach – the climax of the First Symphony’s opening movement and the Trio in the Second Symphony’s Scherzo seemingly moving faster than time itself, while the Berlin strings float the slow movement towards heaven – represented the warmest welcome back possible to Schumann’s dream-built chimeric fantasy world, the heartfelt directness of his melodic fancy played out over structural chess moves. Ticciati’s sometimes manically driven, flintier orchestral sound can be unexpectedly austere; Nézet-Séguin’s cycle is the most unashamedly Romantic of the four, fevered-brow gesturing, rubato with attitude.

Despite their differences, though, the sets are unified by one underlying common denominator – none of them could have been recorded 30, or even 20, years ago. Over the phone from his home in Zurich, Heinz Holliger suppresses a laugh when I ask: why now? Why, suddenly, have maestros gone all Schumann crazy? ‘Well, I started conducting him 30 years ago, when too many conductors had problems with Schumann,’ he reflects. ‘He was never a problem for pianists or composers – Debussy and Berg held him in great esteem – but conductors realised that you cannot try to sight-read Schumann; if you do, the music is completely grey.’ And even 50 shades of grey would not be enough to express Schumann’s multiverse of colour? ‘He does not write out everything; he doesn’t tell you which voice is the principal and which accompanies; nor whether one instrument should have a diminuendo while the others crescendo. To make a Schumann symphony sound light and transparent, as he intended, takes a lot of rehearsal. Each player needs to know whether they’re playing part of only the harmony, or whether they are involved in the counterpoint. Schumann was a great writer of words too, and you need to understand how close the phrasing is to speech. But many conductors are not so interested in this background; they just play what they read.’

Holliger reminds me that Schumann never heard more than 12 first violins during his whole life and, in his view, the period-instrument movement has had a very positive effect on how conductors perceive appropriate orchestral weighting and internal balance. And when I talk to Sir Simon Rattle a few weeks earlier, he makes a characteristically smart analogy: ‘We think of Beethoven and Brahms as being the grizzled old lions of Austro-German symphonic tradition,’ he tells me, ‘but Schumann’s symphonies move like a panther. Beethoven plunges his feet forcefully through the ground; but Schumann’s feet sprint and never fully touch the floor.’

Rattle can’t quite explain why Schumann is suddenly so de rigueur, although sometimes, he says, mysterious forces collude to raise the collective consciousness around a particular composer. But the important thing for Rattle is that distinct and informed conductorly perspectives must all be celebrated. Ticciati’s way is not his way, but Rattle admires enormously how he tackles the 1851 revision of the Fourth Symphony: ‘Robin makes a clear case for how the revised version can retain the radical edge of the 1841 version. Still it sounds like a fireball and I take my hat off to him.’

Which Fourth Symphony? That’s the most fundamental decision any wannabe Schumann conductor must make. To programme the 1841 version is to agree with Brahms, who owned the autograph score and wrote: ‘It is a real pleasure to see anything so bright and spontaneous expressed with corresponding ease and grace.’ He found the revised version charmless and stodgy, and Rattle and Holliger concur with Brahms, and each other, that the first version is much preferable – although they choose to do notably different things with that information. ‘Schumann made the revised piece in a depressive state,’ Rattle says, ‘and Brahms was completely right about the relative merits of the two versions.’ Holliger adds that Schumann’s orchestra in Düsseldorf, which premiered the new version, was nowhere near as honed as the standard of playing he had become accustomed to in Leipzig, while Schumann himself ‘was heavier, and moved and spoke more slowly’. But the pertinent point for Holliger is that Schumann retained his high-velocity metronome marks. Rattle chooses to ignore the later rewrite – Holliger gives us both but attempts to play the 1851 version, as he says, ‘retaining the true spirit of the earlier version’.

Holliger reminds me that he met Rattle 40 years ago when the young conductor invited him to perform Richard Strauss’s Oboe Concerto with the Bournemouth Symphony Orchestra. And Rattle clearly remains in awe of Holliger’s status as a Schumann guru – ‘Ask Heinz, when you speak to him, to tell you about the tempo relationships in the symphonies and about his extraordinary discovery in the fourth movement of the Rhenish Symphony.’ And I’m happy to take my cue from the Music Director of the Berlin Philharmonic.

On paper, and in the mind, Schumann’s Second Symphony registers as the most conventionally ‘symphonic’, its four movement groundplan – with a slow introduction breaking into an Allegro trot – putting you in mind of the first two Beethoven symphonies or of Haydn. And as I began to reacquaint myself with Schumann’s symphonic world, I pondered how a composition that felt instinctively unified melodically and motivically could also sound so disparate and varied, like each movement acting as a standalone character piece (not that you would necessarily want that). Holliger provides an answer.

‘The first and second movements,’ he tells me, ‘have the same metronome mark of crotchet=144, and the slow movement is nearly half; then the finale is in a very fast one-beat-per-bar, but still you feel like each bar matches the beat of the slow movement. The whole symphony is in one, like the conception of Mendelssohn’s Scottish Symphony.’ Holliger explains how the music is glued together throughout by a four-note cell, but I ask him to tell me about the music’s disunity. Am I right to hear each movement orbiting independently too, in a way that is uniquely Schumann? Holliger alludes to Bernd Alois Zimmermann, the composer of Die Soldaten, Photoptosis and Requiem für einen jungen Dichter, who died in 1970, and who was famous for pieces that made liberal use of collage and knitted together layers of borrowed material. ‘He was fascinated by the idea of Kugelgestalt – that time is like a ball, and all times of all centuries are focused in one single point. I think Schumann understood this too. You ask about the Second Symphony – well, the beginning could be like 17th-century polyphony and then, suddenly, it looks 120 years or more into the future. You feel this composer knows the whole history of music.’

The Second Symphony’s Scherzo has something of the lightness of Mendelssohn’s A Midsummer Night’s Dream, Holliger explains as he tells me about those angels and demons, ‘but is relentless, a diabolic dance, in the mood of ETA Hoffmann’. And that shockingly abrupt change of mood, the solo flute overtaken by a brutal march as the first movement of the First Symphony reaches its climax, is another characteristic Schumann moment. ‘In the First Symphony the flute symbolises a butterfly which here is overwhelmed by very tragic music. Marches are a frightening thing. Send soldiers to kill, and you’re asking them to stop thinking about what they are doing. Trills in Schumann, like the woodwind trills you mention, often tremor and shiver like music with a high fever – this is not the Baroque idea of a trill as ornamentation.’

Holliger talks about the symbolism of instrumental identity in Schumann’s music. In Overture, Scherzo and Finale a choir of three trombones appear suddenly like a premonition of the role they will take in the fourth movement of the Rhenish. ‘When his brother Eduard was dying, Schumann woke up at three in the morning. He had been dreaming about three trombones, and later he learnt that his brother had died at 3am. Always in Schumann, three trombones is a message about death.’ I mention that Rattle urged me to ask him about this same movement. ‘Well, when I looked at the sketches, I realised that the tempo changes to double the speed two beats later than in the printed score – nobody ever does this, but the difference is essential.’

That Schumann had such specific ideas about orchestral colour and instrumental identity runs triumphantly contrary to that tired cliché about his orchestration being somehow inept and clumsy. In the September 2014 issue of Gramophone, Robin Ticciati revealed that, for him, the attraction of Schumann is precisely because the orchestration is so, as he put it, ‘crazy’. ‘It’s also so controlled, and the palette is extraordinary. And I think when you get to a Schumann score, the first reaction is not to go, “What is all that?” but “What does he want?” and “What’s important here?”’ Ticciati hears clues about how Schumann ought to sound orchestrally in how he ‘orchestrates’ his piano music; and in the booklet-notes accompanying his cycle, Yannick Nézet-Séguin discusses how the defined attack and decay of modern trumpets help balance the orchestration.

And so Schumann wins. The consensus, circa 2014/15, is leave well alone. ‘Schumann learnt lots about orchestration from Mendelssohn, the greatest orchestrator of his time,’ Holliger explains, ‘and he tried to have a very transparent sound in the orchestra. It’s not that very heavy “German potato soup” sound. I never change a single note in any of the symphonies.’ Rattle confirms that Schumann must be ‘light and singing, or the sound can be too brittle – the key word is sostenuto.’ The impulsive and spontaneous side of Schumann is also important to Rattle. ‘The last symphonic music Schumann wrote was the Rhenish,’ he says, ‘and the fourth movement feels like Schumann falling apart, then the finale is an attempt to cradle him in a warm embrace. And for that to work, you can’t micromanage too heavily.’ Music to Schumann’s ears, I suspect – a composer who clearly knew the value of spontaneity: ‘My symphonies would have reached Opus 100 if I had but written them down,’ he said. ‘Sometimes I am so full of music, and so overflowing with melody, that I find it simply impossible to write anything.’

www.opusklassiek.nl | mei 2015 | Siebe Riedstra | May 1, 2015

De Zwitserse hoboïst, componist en dirigent Heinz Holliger heeft zich in al zijn disciplines intensief met het werk van Schumann beziggehouden. Als componist leidde dat tot verassende resultaten, getuige zijn Romancendres (hier besproken door Aart van der Wal). Als dirigent munt Holliger in de eerste plaats uit door een buitengewoon scherp en precies gehoor, tot op de Herz nauwkeurig. Zijn slagtechniek sluit niet naadloos aan op die precisie, en dat hoor je bijvoorbeeld in de wat rommelige start van de Eerste symfonie. Mehr lesen

Fono Forum | Dezember 2014 | Stephan Schwarz | December 1, 2014

Kritiker-Umfrage 2014

Die 10 besten Aufnahmen des Jahres 2014

Selten hatte man das Gefühl, ein Dirigent könnte einem Komponisten so in den Kopf schauen wie Heinz Holliger Robert Schumann.<br /> Mehr lesen

www.artalinna.com | 23 octobre 2014 | Jean-Charles Hoffelé | October 23, 2014 L’orchestre réinventé

Soudain l’orchestre se creuse, les accords claquent, le geste devient péremptoire : on le comprend, Schumann symphoniste s’est trouvé. Les pupitres de la WDR peuvent chanter autant qu’ils le veulent, Holliger les accompagne d’un geste enthousiaste, presque avec ivresse.Mehr lesen

www.concertonet.com | 09/15/2014 | Simon Corley | September 15, 2014

Son Schumann se révèle souvent inattendu – pour la Quatrième, il a d’ailleurs préféré la version de 1841, plus abrupte et anguleuse, qu’il est toujours passionnant de confronter à la mouture définitive de 1851: raffiné, aérien, aéré, volontiers chambriste, d’une grande lisibilité, il convainc davantage dans la juvénile Première, dans le triptyque Ouverture, Scherzo et Finale et, peut-être plus encore, dans une puissante et fougueuse Deuxième.Mehr lesen

www.musicweb-international.com | September 2014 | Brian Wilson | September 1, 2014

There’s no special price for the Audite recording but, at $12.02 – just over £7 at current rates – it won’t break the bank and it’s wellMehr lesen

The Audite recording is good throughout, though I miss those powerful drum thwacks, so apparent on the Linn recording. If you bought the first volume (Audite 97.677, Symphony No. 1 and No. 4, original version, and Overture, Scherzo and Finale) I’m sure you’ll want the second. The third volume, containing the Cello Concerto and final version of the Fourth Symphony, is due for release in October 2014.

I should add that I haven’t yet heard the new, highly-regarded BPO/Simon Rattle set – review – except for the 1-minute segments from Qobuz, but I see that he attributes his appreciation of Schumann to a meeting long ago with Heinz Holliger, whom he describes as a Schumann ‘nut’ – endorsement of a kind for his mentor’s new recording.

Stereoplay | 09/2014 (September 2014) | Michael Stegmann | September 1, 2014 Vier mal vier

Wo Rattle also den Romantiker Schumann betont, Järvi den Klassizisten und Nezet-Seguin den Verrückten, da steht Heinz Holliger mit dem WDR Sinfonieorchester Köln scheinbar zwischen allen Lösungen, was aber nicht unbedingt die schlechteste Wahl ist. [...] Vielleicht hat die Erfahrungs- und Ideenwelt des Komponisten Holliger hier den Taktstock geführt; jedenfalls hat er mich von den vier Aufnahmen am häufigsten überrascht.Mehr lesen

Scherzo | mayo 2014 | Juan Garcìa-Rico | May 1, 2014

siehe PDFMehr lesen

F. F. dabei | Nr. 6/2014 | March 8, 2014 Die sinfonischen Werke, Volume 1

Holligers Interpretationen beruhen auf seiner fast lebenslangen Beschäftigung mit dem Werk, dem Denken, der Persönlichkeit und dem Schicksal Robert Schumanns. Das verbreitete Bild des Romantikers als schwachem Orchestrator erfährt durch Holliger eine erfrischende und fundierte Korrektur.Mehr lesen

Diapason | N° 622 Mars 2014 | Rémy Louis | March 1, 2014

Heinz Holliger succède à Christian Zaccharias dans le club des instrumentistes qui, s'étant illustrés dans le Schumann chambriste, se frottentMehr lesen

Choix heureux, tant le musicien Suisse semble avoir pleinement façonné les instrumentistes colonais à ses vues expressives, qui reposent à l'évidence sur une écoute mutuelle très poussée: c'est la première impression, forte, que l'on reçoit. La deuxième est que si chaque détail, chaque respiration sont pensés et mesurés, rien ne paraît jamais forcé – bien des moments affichent au contraire une étonnante douceur. La clarté lumineuse de ses lectures ressort d'un travail très subtil (chambriste) sur la trame orchestrale et de la recherche d'une expression limpide.

Comme Zaccharias, Jarvi, Dausgaard, SchØnwandt ou encore Zinman – pour ne rien dire de ceux qui ont préféré les instruments anciens –, Holliger a fait siennes les données stylistiques qui ont renouvelé l'interprétation du répertoire romantique allemand depuis trente ans. Chez lui aussi (qui est un compositeur important), elles ont pour effet immédiat d'alléger et d'aérer l'orchestre schumannien. Mais si la pulsation est vive (les pulsations, devrait-on écrire), le tempo n'est en rien précipité, et les événements sonores demeurent d'une grande fraîcheur d'inspiration. L'irrésistible triptyque Ouverture, scherzo et finale l'illustre de façon très convaincante. L'élan modéré de l'Ouverture permet aux détails (et aux solos) de se déployer en toute liberté, donnant au tempo soudain plus accentué de la coda une force particulière (idem à la fin de la Symphonie n° 4). Le halètement du scherzo est somptueusement dosé (accents, articulations, poids), qui préserve toujours un mystère, une ambivalence, en contraste avec la flamboyance du finale, et ses cordes ailées.

Analyse serrée de l'écriture schumannienne, poésie des timbres, expression conséquente: écoutez dans l'Allegro final de la «Printemps», comment, avant la reprise du thème, il enchaîne le trille de la flûte au choral des cors (d'un romantisme wéberien ... qui ressurgit dans le célèbre enchaînement Scherzo-Finale de la 4e). La plasticité extrêmement élaborée – mais fluide! – de la texture orchestrale (Larghetto de la «Printemps», Romanza de la 4e) rejoint l'imagination constante de l'expression, tout à tour souriante, nostalgique, rêveuse, conquérante.

Tant dans la Symphonie n° 1 que dans la 4e – dont la version princeps trouve ici une gravure particulièrement accomplie –, la subtilité du rythme et des impulsions fait vivre singulièrement les phrases, illumine le moindre contre-chant, sans jamais troubler une direction franche mais jamais univoque. Si l'entreprise d'Holliger se poursuit à ce niveau, nous tiendrons là l'un des cycles Schumann modernes les plus réussis.

Das Orchester | 03/2014 | Thomas Bopp | March 1, 2014

Holliger deutet diesen Finalsatz hoch analytisch aus. Und das ausgeklügelte spieltechnische Niveau des WDR Sinfonieorchesters Köln und die enorm transparente Klangtechnik befördern diesen Eindruck noch um ein Zusätzliches. Die Wiedergabe der frühen d-Moll Sinfonie zeigt sich sehr schlank und durchhörbar. Gegenüber dem etwas holzschnittartig aufgerauten Kopfsatz bringt Holliger den Finalsatz trotz der durchscheinenden schablonenhaften Struktur zu einem spürbaren Pulsieren.Mehr lesen

Musik & Theater | März 2014 | Reinmar Wagner | March 1, 2014 Gelungener Start

Das Resultat überzeugt auf der ganzen Linie: Holliger hält das Geschehen mit wacher Dynamik und stets beweglicher Agogik im Fluss. Klanglich pflegt er mit den versierten Orchestermusikern eine im Bewusstsein damals zeitgemäßer Artikulierungen und Spielweisen geschulte Gangart, und zeigt damit unter anderem auch, dass das Vorurteil von Schumann als mittelmäßigem Orchestrator ein Missverständnis des 20. Jahrhunderts ist.Mehr lesen

classical ear | 27 February 2014 | Emily DeVoto | February 27, 2014

Holliger’s light-toned and vivid approach provides much that is joyful and life-enhancing: details sparkle, rhythms dance and melodies touch the heart while ebbing with emotion. [...] Playing, recording, production and presentation are top drawer. Volume 2 please, soon!Mehr lesen

Neue Zürcher Zeitung | 21.02.2014 | tsr | February 21, 2014 Schumanns Sinfonien mit Heinz Holliger

Holliger streicht die Vorzüge der seiner Meinung nach besseren Urfassung mit aller Deutlichkeit heraus: Hauptmerkmal ist der aus der Instrumentation abgeleitete kammermusikalische Ansatz. Damit verbunden zeigt sich eine Transparenz, welche die sogenannten Nebenstimmen nicht unter den Tisch wischt. Die Klangbalance wird gerne zugunsten der Bläser verschoben. Die Artikulation der Melodien ist sehr deutlich. Die Tempi bewegen sich eher auf der schnellen Seite und werden unbeugsam durchgehalten. Alles in allem eine Interpretation, die durch Konsequenz, Strenge und eine gewisse Schärfe auffällt.Mehr lesen

classical ear | Friday February 14, 2014 | Colin Anderson | February 14, 2014

details sparkle, rhythms dance and melodies touch the heart while ebbing with emotion. [...] These carefully crafted yet vivacious performances are thoroughly involving and illuminating. Playing, recording, production and presentation are top drawer. Volume 2 please, soon!Mehr lesen

Fanfare | February 2014 | Steven Kruger | February 12, 2014

There is often some trepidation to experience at the arrival of a new Schumann CD. Few composers sound so different from performance to performance asMehr lesen

This CD represents a doubly happy surprise, then. The music simply leaps from the loudspeakers, full of energy, joy, originality, and sound of remarkable warmth. So far as I can determine, the WDR SO is playing in substantial numbers, if not perhaps full strength. But no Norrington twang invades the string passages. Nor do I hear melodies chopped up into Baroque bits and pieces. Although the notes are more informative about Schumann’s psychology than the conductor’s performance practice, Holliger clearly favors a fruitier, more original sound from the brasses than usual – and the occasional harder impact from timpani.

What struck me foremost is how the introduction to the Spring Symphony leaps off the page. Holliger takes it fast and explosively. He begins with the fanfare voiced down a harmonic third, where it avoids blattiness. (Otherwise, this is the usual version of the work.) As the Symphony proceeds, it strikes me Holliger has found a way of integrating tempos in the music as though it were a piano piece. The actual thrust and velocity we hear are quite normal, but contrasting passages seem more vivid and, where appropriate, more mercurial. Textures become magical in places you might not expect. Plodding boredom is avoided. And traditional criticism of Schumann’s orchestration is dealt a serious blow yet again.

Performances of this work can rise or fall with the great fanfare climax in the middle of the first movement. There is nothing worse than just letting it go by stiffly. It can be a litmus test for time-beaters. Here, I’m happy to say Holliger gives us a beautifully judged ritard, and the extra champagne fizz from his brasses makes it a joyous and triumphant experience. I couldn’t resist playing it over several times. The slow movement is the other standout here, flowing along more swiftly than we might expect but losing no sentiment along the way – and avoiding boredom in places where we might have been reluctant to admit its existence in the past.

The rest of the Symphony unfolds in the same lively manner, as does the remainder of the CD. The Overture, Scherzo, and Finale is given a traditional but zesty account. The slightly smaller scale of the piece reinforces the notion of piano music, beautifully orchestrated and performed. But if there is another revelation, I’d say it is to be found in the original version of the Fourth Symphony, which rounds out the CD. Holliger has discovered that the key to this work is to let the textures dictate the tempo. Other conductors often give the impression of trying to make a big piece out of it – whereupon they fall prey to bizarre holes in the orchestration and the many places where Schumann doesn’t support this idea with appropriate weight. But take the music on its own terms, the way Holliger does here, play a good bit of it for deft movement, and suddenly this early version leaps forth with charm. Ultimately, for sheer power, I favor the reorchestrated, nearly Brahmsian version we have all come to know and love. But here, for the first time, I understand how Brahms could have preferred the original.[…]

www.classicalsource.com | February 2014 | Antony Hodgson | February 1, 2014 Heinz Holliger conducts Robert Schumann’s Complete Symphonic Works – Volume 1, Spring Symphony

For all that, this impressive performance (played and recorded with excellence, as throughout) leaves in no doubt that Heinz Holliger is a conductor with a great understanding of Schumann. I look forward to the continuance of this Audite series and I foresee an exceptional reading of the revised version of No.4.Mehr lesen

Fono Forum | Februar 2014 | Stephan Schwarz | February 1, 2014 Nebenstimmen

Das sinfonische Werk Schumanns schien gut erschlossen. Und doch freut man sich, dass sich in letzter Zeit bedeutende Klangkörper und DirigentenMehr lesen

Schon lange bindet den Komponisten Holliger eine enge Beziehung an den Komponisten Schumann. Diesen in seinem Inneren zu verstehen, ihm gewissermaßen ins Hirn zu schauen ist ein Teil seiner Arbeit als Dirigent. Exemplarisch für die Akribie, mit der Holliger dieses Ansinnen verfolgt, ist die erste Sinfonie, die hier an vielen Stellen ganz auf den Kopf gestellt zu sein scheint. Takt für Takt erkundet Holliger die Partitur auf ihre eigentliche Handlung. Gerade so, als käme sie bei einer Explosion desselben direkt aus Schumanns Kopf geschossen, stürzt schon die Einleitung über den Hörer hinweg, und man merkt sofort, worauf es dem Dirigenten ankommt: Es sind die Nebenstimmen. Der erste Satz wird wunderbar widerborstig durch sie, neurotisch wuselnd bringen sie eine befremdliche Unruhe in den zweiten, und die koboldhaften Skurrilitäten des vierten sind wundervoll hervorgehoben. Dass dabei manches auf den ersten Blick nicht ganz nachvollziehbar ist, wie etwa die seltsam breit gewalzten Töne im ersten Trio des Scherzo, ist bei einem solch eigenwilligen Zugriff nicht verwunderlich. Aber wie modern klingt dieser Schumann, auch in der seltener aufgeführten "Dreiviertelsinfonie", "Ouvertüre, Scherzo und Finale" und der d-Moll-Sinfonie, die hier viel von ihrer schwarzen Melancholie verliert.

??? | Samstag, 18. Januar 2014 | Greg Keane | January 18, 2014

"Holliger's profound empathy for Schumann shines through this outstanding performance which sustain." (BBC Music Magazine)<br /> <br /> "Holliger is one ofMehr lesen

"Holliger is one of those musicians who hears what he conducts from inside, a crucial virtue in Schumann and neat way to disqualify curmudgeonly commentators who wrongly accuse Schumann of ineptitude in orchestration...Holliger is en route to a complete cycle...His may well be the one to go for." (Gramophone)

"Auspicious start to a Schumann cycle set to throw up a few revelations." (Limelight)

"Holliger is one of

klassik.com

| 13.01.2014 | Marion Beyer | January 13, 2014 | source: http://magazin.k...

Mit Elan

Schumann, Robert - Sämtliche symphonische Werke Vol. 1

Heinz Holligers Herangehensweise an die ersten beiden Sinfonien, die Schumann jeweils innerhalb sehr kurzer Zeiträume komponierte, und an 'Ouvertüre, Scherzo und Finale' op. 52 ist voller Elan und einem spürbar großen Willen, den tiefen Kern der Werke Schumanns erfahrbar werden zu lassen. [...] <br /> Die erste Folge im Rahmen der Gesamteinspielung sämtlicher Instrumentalwerke Schumanns mit Orchester zeigt sich von hoher Qualität und nimmt aufgrund der treffsicheren, geist- und schwungvollen Umsetzung für sich ein.Mehr lesen

Die erste Folge im Rahmen der Gesamteinspielung sämtlicher Instrumentalwerke Schumanns mit Orchester zeigt sich von hoher Qualität und nimmt aufgrund der treffsicheren, geist- und schwungvollen Umsetzung für sich ein.

hifi & records | 1/2014 | Ludwig Flich | January 1, 2014

Schumann-Symphonien sind, so Orchestermusiker, schwieriger zu spielen alsMehr lesen

International Record Review | January 2014 | Patrick Rucker | January 1, 2014

Is there a group of orchestral works in the Romantic canon more vexed than the Schumann symphonies? Indisputably lovely works that have long since wonMehr lesen

A new project which aims to record all of Schumann's orchestral music, including the concertante works and overtures , is now under way with the West German Radio Symphony Orchestra of Cologne under the Swiss oboist, composer and conductor Heinz Holliger. The first instalment, recorded in January and March of 2012, presents the 'Spring' Symphony, the first version of what would become the Fourth Symphony, and the Overture, Scherzo and Finale, Op. 52. While the performances are unquestionably earnest and dutiful throughout, one yearns for moments that seem insightful or inspired. The playing is never less than highly competent without being particularly exciting. A rather contained and old-fashioned recorded sound is not helpful though, in and of itself, more lifelike sound reproduction could scarcely create compelling Schumann. Sad to say it is unlikely that this recording will be a stand-out in the Cologne West German Radio Symphony Orchestra's modest discography or, for that matter, in Holliger's more extensive one.

Fortunately there are many, many other choices. Furtwängler, always much admired as a Schumann exponent, recorded only the First and Fourth Symphonies, but these are available on several labels. Of more modern interpretations, few have garnered the enthusiastic accolades of the set by John Eliot Gardiner and the Orchestre Révolutionnaire et Romantique. Though already 16 years old, for cutting-edge interpretative insights, brilliant sound and appropriately sized forces, these recordings have not been surpassed.

Image Hifi | 1/2014 | Heinz Gelking | January 1, 2014 Musik macht dumm

Man hat Schumanns Musik vielleicht schon raffiniert-feinnerviger gehört, aber selten so formbewusst und mit diesem klaren Blick auf ihren kontrapunktischen Bau. Darin liegt der Zauber dieser Aufnahmen.Mehr lesen

www.pizzicato.lu | 26/12/2013 | Remy Franck | December 26, 2013 Holligers schlanker Schumann

Mit dieser CD beginnt bei Audite eine umfassende Reihe mit Einspielungen aller Orchesterwerke von Robert Schumann mit dem WDR Sinfonieorchester unterMehr lesen

Heinz Holliger ist ein äußerst vielseitiger Musiker, der als Komponist, Dirigent und Oboist gleichermaßen Berühmtheit erlangte. Für Robert Schumann hegt er eine große Leidenschaft, er dirigiert seine Werke oft und er gibt zu, dass Schumann quasi in jeder seiner eigenen Kompositionen präsent ist. Er sagte auch einmal, er komme bei Schumann in seinen analytischen Betrachtungen nie an ein Ende: «Es gibt immer neue Türen, die sich öffnen. Nach der geöffneten Tür kommt eine weitere und dann noch eine und noch eine.»

Heinz Holligers Interpretationen beruhen also auf seiner langen Beschäftigung mit dem Werk und der Person Robert Schumanns. Und das hört man. Sie sind sehr ausgefeilt, und die Detailarbeit, die er vom Orchester fordert, hat gewiss viel Probenzeit konsumiert. Das Resultat ist ein sehr transparenter, farblich aufgefrischter und schlank-flüssiger Schumann, mit zum Teil kühnen Rubati und einer deutlichen Aufwertung der Holzbläser gegenüber den quasi vibratolos spielenden Streichern. Direkt revolutionär ist das alles nicht, aber spannend ist es allemal.

Nothing revolutionary here, but we admire an extremely careful and refined playing, transparent, fluid and svelte, with bright colors and unusual accentuations and rubati.

Pizzicato | N° 238 - 12/2013 | RéF | December 1, 2013 Holligers schlanker Schumann

Mit dieser CD beginnt bei Audite eine umfassende Reihe mit Einspielungen aller Orchesterwerke von Robert Schumann mit dem WDR Sinfonieorchester unterMehr lesen

Heinz Holliger ist ein äußerst vielseitiger Musiker, der als Komponist, Dirigent und Oboist gleichermaßen Berühmtheit erlangte. Für Robert Schumann hegt er eine große Leidenschaft, er dirigiert seine Werke oft und er gibt zu, dass Schumann quasi in jeder seiner Kompositionen präsent ist. Er sagte auch, er komme bei Schumann in seinen analytischen Betrachtungen nie an ein Ende: "Es gibt immer neue Türen, die sich öffnen. Nach der geöffneten Tür kommt eine weitere und dann noch eine und noch eine."

Heinz Holligers Interpretationen beruhen also auf seiner langen Beschäftigung mit dem Werk und der Person Robert Schumanns. Und das hört man. Holligers Interpretation sind sehr ausgefeilt, die Detailarbeit, die er vom Orchester fordert, hat gewiss viel Probenzeit konsumiert. Das Resultat ist ein sehr transparenter, farblich aufgefrischter und schlanker Schumann, mit zum Teil kühnen Rubati und einer deutlichen Aufwertung der Holzbläser gegenüber den quasi vibratolos spielenden Streichern. Direkt revolutionär ist das alles nicht, aber spannend ist es allemal.

BBC Music Magazine | Christmas 2013 | EL | December 1, 2013

Holliger's profound empathy for Schumann shines through these outstanding performances which sustain a miraculous transparency of orchestral textureMehr lesen

Stereoplay | Dezember 2013 | Martin Mezger | December 1, 2013

Feingliedrig und filigran, aber auch sehnig gespannt modelliert Holligers grundsätzlich kammermusikalische Herangehensweise mit den WDR-Sinfonikern die thematischen Figuren und ihre Entwicklung.Mehr lesen

Ostthüringer Zeitung | 23.11.2013 | Dr. sc. Eberhard Kneipel | November 23, 2013

Leicht, klar und schön

Dr. sc. Eberhard Kneipel über eine bemerkenswerte Neueinspielung bei audite

Holligers Liebe zum Detail, zu Farbnuancen, melodischen Finessen, zu genauer Artikulation und sorgsamen Spannungsaufbau macht deutlich, welch neue Töne, welch frische Tempi und welche Transparenz er diesen wundervollen Partituren und diesem wunderbaren Orchester abzugewinnen vermag.Mehr lesen

Infodad.com | November 14, 2013 | November 14, 2013 Concerto and symphonic cycles

Holliger’s well-thought-out, well-put-together performances bode well for this Audite series, and if the mix here of popular and less-known works continues in future volumes, this group of releases – like the Grieg series – will be a notable one indeed.Mehr lesen

The Guardian | Thursday 7 November 2013 | Andrew Clements | November 7, 2013

[...] the touch is always light, and Holliger's ear for texture acute. Schumann's freewheeling genius may not always have been attuned to symphonic thinking, but what he brought to the form was always fresh and distinctive.Mehr lesen

WDR 3 | WDR Sinfonieorchester / Diskografie | November 1, 2013

Drei Symphonien des Düsseldorfer Komponisten Robert Schumann (1810-1856)Mehr lesen

www.myclassicalnotes.com | Tuesday | 11.05.13 | May 11, 2013 Holliger’s Schumann

Holliger’s performances draw on a lifetime study of Schumann’s music, thought, personality and fate. His approach imparts lightness and clarity to these scores through a balance of parts, delicately gradated dynamics and thoughtful tempos. The widespread image of this romantic composer as a weak orchestrator receives an interpretation that corrects that point of view.Mehr lesen

Gramophone | 17.03.2015 | Philip Clark

Music that grapples with demons and is never wholly at ease, even when wings bless the darkness with glimpses of light—when you’re RobertMehr lesen

The symphonic models are clear and we hear the ghostly spectre of Haydn, Mozart, Beethoven, Brahms and Mendelssohn—but no one has told Schumann’s material that it needs to conform, and the music cannot help but spill over any frame its composer attempts to place around it. The first movement of his Symphony No 1 reaches an apparent cathartic end-point as a solo flute line marked dolce reconciles grinding harmonic and structural inner tensions. Time to stop this madness. But then brass, percussion and trilling woodwinds unleash a stampeding burlesque march. Baleful chromatic inclines smudge the harmony, like Offenbach or Sousa turned on their dark side, and such instability derives from the restlessness of Schumann’s mind, you think, rather than being an overtly conceptual compositional strategy. The free jazz of the Second Symphony’s sostenuto assai prologue, C major credentials asserted by having the strings play anything but, as the brass sustain pure C major triads; in the Third Symphony, that extra movement that sneaks in before the finale, a cobwebby and gothic reimagining of the grounding contrapuntal principles of Renaissance music and Bach; and the audacious cyclic structure of the Fourth Symphony, each movement played attacca and dovetailing into the next. This music of demons and angels grapples also with angles—to take on structure, awkward punctuation, Schumann pushing form, his personal mission being to remould the symphony. And when the realisation dawns that Schumann composed the first version of what would become his Fourth Symphony in the same year as his First Symphony, eyes blink in astonishment. The natural order of things would be to presume that Schumann’s streamlined Fourth Symphony is a perfect distillation of the first three symphonies—but the pathway through Schumann’s symphonic journey is filled with unexpected and improbable twists and turns.

Deciding to record a cycle of the Schumann symphonies begs the question: what exactly should be recorded? And complementary but divergent ideas about the Schumann symphonies have been paraded as rarely before, with four major conductors during the past 18 months releasing four major cycles on disc. Sir Simon Rattle, with the Berlin Philharmonic, gives us four symphonies with the early 1841 version of the Fourth, while Yannick Nézet-Séguin (and the Chamber Orchestra of Europe) and Robin Ticciati (with the Scottish Chamber Orchestra) opt for Schumann’s 1851 revised version. But Heinz Holliger and the WDR Symphony Orchestra of Cologne—like Sir John Eliot Gardiner and his Orchestre Révolutionnaire et Romantique, whose trailblazing 1997 Schumann cycle was given the boxed-up DG reissue treatment last year—perceive Schumann’s symphonic evolution in seven stages. When Holliger completes his cycle during the next year and a half, Schumann’s early Symphony in G minor (the Zwickau Symphony) will take its place alongside the first three canonic symphonies, both versions of the Fourth, and the oftenoverlooked mini-me symphony Overture, Scherzo and Finale—Schumann’s compositional twists of fate put into historical context by a composer/conductor/oboist who has been obsessed with the composer’s enigma for more than 40 years.

I made Rattle’s cycle my Critics’ Choice album of the year in the December 2014 issue; I’ve also elevated Nézet-Séguin’s to an equivalent position in the past. Ticciati’s set has given me much pleasure too, and even more to think about. Nézet-Séguin and Ticciati deploy chamber-orchestra string sections, with Ticciati most explicitly evoking period-instrument practice. Rattle’s Berlin set carries its weightier orchestral ballast very elegantly, and his set became my portal back to Schumann after a longer period than I care to admit when my listening had been dominated by Beethoven, Brahms and Bruckner. Rattle’s opulent, rapacious approach—the climax of the First Symphony’s opening movement and the Trio in the Second Symphony’s Scherzo seemingly moving faster than time itself, while the Berlin strings float the slow movement towards heaven—represented the warmest welcome back possible to Schumann’s dream-built chimeric fantasy world, the heartfelt directness of his melodic fancy played out over structural chess moves. Ticciati’s sometimes manically driven, flintier orchestral sound can be unexpectedly austere; Nézet-Séguin’s cycle is the most unashamedly Romantic of the four, fevered-brow gesturing, rubato with attitude.

Despite their differences, though, the sets are unified by one underlying common denominator—none of them could have been recorded 30, or even 20, years ago. Over the phone from his home in Zurich, Heinz Holliger suppresses a laugh when I ask: why now? Why, suddenly, have maestros gone all Schumann crazy? ‘Well, I started conducting him 30 years ago, when too many conductors had problems with Schumann,’ he reflects. ‘He was never a problem for pianists or composers—Debussy and Berg held him in great esteem—but conductors realised that you cannot try to sight-read Schumann; if you do, the music is completely grey.’ And even 50 shades of grey would not be enough to express Schumann’s multiverse of colour? ‘He does not write out everything; he doesn’t tell you which voice is the principal and which accompanies; nor whether one instrument should have a diminuendo while the others crescendo. To make a Schumann symphony sound light and transparent, as he intended, takes a lot of rehearsal. Each player needs to know whether they’re playing part of only the harmony, or whether they are involved in the counterpoint. Schumann was a great writer of words too, and you need to understand how close the phrasing is to speech. But many conductors are not so interested in this background; they just play what they read.’

Holliger reminds me that Schumann never heard more than 12 first violins during his whole life and, in his view, the period-instrument movement has had a very positive effect on how conductors perceive appropriate orchestral weighting and internal balance. And when I talk to Sir Simon Rattle a few weeks earlier, he makes a characteristically smart analogy: ‘We think of Beethoven and Brahms as being the grizzled old lions of Austro-German symphonic tradition,’ he tells me, ‘but Schumann’s symphonies move like a panther. Beethoven plunges his feet forcefully through the ground; but Schumann’s feet sprint and never fully touch the floor.’

Rattle can’t quite explain why Schumann is suddenly so de rigueur, although sometimes, he says, mysterious forces collude to raise the collective consciousness around a particular composer. But the important thing for Rattle is that distinct and informed conductorly perspectives must all be celebrated. Ticciati’s way is not his way, but Rattle admires enormously how he tackles the 1851 revision of the Fourth Symphony: ‘Robin makes a clear case for how the revised version can retain the radical edge of the 1841 version. Still it sounds like a fireball and I take my hat off to him.’

Which Fourth Symphony? That’s the most fundamental decision any wannabe Schumann conductor must make. To programme the 1841 version is to agree with Brahms, who owned the autograph score and wrote: ‘It is a real pleasure to see anything so bright and spontaneous expressed with corresponding ease and grace.’ He found the revised version charmless and stodgy, and Rattle and Holliger concur with Brahms, and each other, that the first version is much preferable—although they choose to do notably different things with that information. ‘Schumann made the revised piece in a depressive state,’ Rattle says, ‘and Brahms was completely right about the relative merits of the two versions.’ Holliger adds that Schumann’s orchestra in Düsseldorf, which premiered the new version, was nowhere near as honed as the standard of playing he had become accustomed to in Leipzig, while Schumann himself ‘was heavier, and moved and spoke more slowly’. But the pertinent point for Holliger is that Schumann retained his high-velocity metronome marks. Rattle chooses to ignore the later rewrite—Holliger gives us both but attempts to play the 1851 version, as he says, ‘retaining the true spirit of the earlier version’.

Holliger reminds me that he met Rattle 40 years ago when the young conductor invited him to perform Richard Strauss’s Oboe Concerto with the Bournemouth Symphony Orchestra. And Rattle clearly remains in awe of Holliger’s status as a Schumann guru—‘Ask Heinz, when you speak to him, to tell you about the tempo relationships in the symphonies and about his extraordinary discovery in the fourth movement of the Rhenish Symphony.’ And I’m happy to take my cue from the Music Director of the Berlin Philharmonic.

On paper, and in the mind, Schumann’s Second Symphony registers as the most conventionally ‘symphonic’, its four movement groundplan—with a slow introduction breaking into an Allegro trot—putting you in mind of the first two Beethoven symphonies or of Haydn. And as I began to reacquaint myself with Schumann’s symphonic world, I pondered how a composition that felt instinctively unified melodically and motivically could also sound so disparate and varied, like each movement acting as a standalone character piece (not that you would necessarily want that). Holliger provides an answer.

‘The first and second movements,’ he tells me, ‘have the same metronome mark of crotchet=144, and the slow movement is nearly half; then the finale is in a very fast one-beat-per-bar, but still you feel like each bar matches the beat of the slow movement. The whole symphony is in one, like the conception of Mendelssohn’s Scottish Symphony.’ Holliger explains how the music is glued together throughout by a four-note cell, but I ask him to tell me about the music’s disunity. Am I right to hear each movement orbiting independently too, in a way that is uniquely Schumann? Holliger alludes to Bernd Alois Zimmermann, the composer of Die Soldaten, Photoptosis and Requiem für einen jungen Dichter, who died in 1970, and who was famous for pieces that made liberal use of collage and knitted together layers of borrowed material. ‘He was fascinated by the idea of Kugelgestalt—that time is like a ball, and all times of all centuries are focused in one single point. I think Schumann understood this too. You ask about the Second Symphony—well, the beginning could be like 17thcentury polyphony and then, suddenly, it looks 120 years or more into the future. You feel this composer knows the whole history of music.’

The Second Symphony’s Scherzo has something of the lightness of Mendelssohn’s A Midsummer Night’s Dream, Holliger explains as he tells me about those angels and demons, ‘but is relentless, a diabolic dance, in the mood of ETA Hoffmann’. And that shockingly abrupt change of mood, the solo flute overtaken by a brutal march as the first movement of the First Symphony reaches its climax, is another characteristic Schumann moment. ‘In the First Symphony the flute symbolises a butterfly which here is overwhelmed by very tragic music. Marches are a frightening thing. Send soldiers to kill, and you’re asking them to stop thinking about what they are doing. Trills in Schumann, like the woodwind trills you mention, often tremor and shiver like music with a high fever—this is not the Baroque idea of a trill as ornamentation.’

Holliger talks about the symbolism of instrumental identity in Schumann’s music. In Overture, Scherzo and Finale a choir of three trombones appear suddenly like a premonition of the role they will take in the fourth movement of the Rhenish. ‘When his brother Eduard was dying, Schumann woke up at three in the morning. He had been dreaming about three trombones, and later he learnt that his brother had died at 3am. Always in Schumann, three trombones is a message about death.’ I mention that Rattle urged me to ask him about this same movement. ‘Well, when I looked at the sketches, I realised that the tempo changes to double the speed two beats later than in the printed score—nobody ever does this, but the difference is essential.’

That Schumann had such specific ideas about orchestral colour and instrumental identity runs triumphantly contrary to that tired cliché about his orchestration being somehow inept and clumsy. In the September 2014 issue of Gramophone, Robin Ticciati revealed that, for him, the attraction of Schumann is precisely because the orchestration is so, as he put it, ‘crazy’. ‘It’s also so controlled, and the palette is extraordinary. And I think when you get to a Schumann score, the first reaction is not to go, “What is all that?” but “What does he want?” and “What’s important here?”’ Ticciati hears clues about how Schumann ought to sound orchestrally in how he ‘orchestrates’ his piano music; and in the booklet-notes accompanying his cycle, Yannick NézetSéguin discusses how the defined attack and decay of modern trumpets help balance the orchestration.

And so Schumann wins. The consensus, circa 2014/15, is leave well alone. ‘Schumann learnt lots about orchestration from Mendelssohn, the greatest orchestrator of his time,’ Holliger explains, ‘and he tried to have a very transparent sound in the orchestra. It’s not that very heavy “German potato soup” sound. I never change a single note in any of the symphonies.’ Rattle confirms that Schumann must be ‘light and singing, or the sound can be too brittle—the key word is sostenuto.’ The impulsive and spontaneous side of Schumann is also important to Rattle. ‘The last symphonic music Schumann wrote was the Rhenish,’ he says, ‘and the fourth movement feels like Schumann falling apart, then the finale is an attempt to cradle him in a warm embrace. And for that to work, you can’t micromanage too heavily.’ Music to Schumann’s ears, I suspect—a composer who clearly knew the value of spontaneity: ‘My symphonies would have reached Opus 100 if I had but written them down,’ he said. ‘Sometimes I am so full of music, and so overflowing with melody, that I find it simply impossible to write anything.’

Gramophone | 26.12.2013 | Rob Cowan Holliger launches Schumann symphonic cycle in Cologne

Right from the off, things augur well. The Spring Symphony’s opening Andante un poco maestoso is also, usefully, con moto, which means a refreshingMehr lesen

Aside from its Faustian opening, the wonderful symphony in three movements that goes by the name of Overture, Scherzo and Finale breathes Mendelssohnian fresh air, even though the Scherzo seems to suggest infant Valkyries. The Finale’s coda blazes triumphantly, which leaves what’s called in this context the Symphony in D minor, in reality the Fourth in its original 1841 incarnation, leaner, lighter and more abrupt than the familiar revision and with some different thematic material. It’s useful to have, though there can be little doubt that Schumann’s later thoughts were his best, and by some considerable distance. Precise playing and fine, detailed sound guarantee a generous pleasure quota. Other excellent Schumann conductors on disc such as Rafael Kubelik (DG), Fabio Luisi (Orfeo), Paavo Järvi (RCA or C Major on DVD), David Zinman (Arte Nova) and Thomas Dausgaard (BIS) remain on hand as viable alternatives; but, as Holliger is en route to a complete cycle, I’d hold on to your shekels, at least for the moment. His may well be the one to go for.

http://theclassicalreviewer.blogspot.de | Sunday, 1 December 2013 Heinz Holliger and the WDR Sinfonieorchester Köln bring much clarity and detail to Schumann, as well as joy and flair, in this first volume of the Complete Symphonic Works on Audite

Holliger and his orchestra bring so much clarity and detail to Schumann as well as joy and flair. These performances have made me hear Schumann with fresh ears and bodes well for future Schumann issues from this team.Mehr lesen